The following is an excerpt (pages 137-144) from Ancient and Medieval History (1946) by Francis S. Betten, S.J. Although some information may be outdated, the Catholic historical perspective it provides remains pertinent. Use the link at the bottom of post to read the previous/following pages. Use the Search box above to find specific topics or browse using the Resources tab above.

CHAPTER XIV

PERIOD OF DECLINE

THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR, 431-404

This war, lasting twenty-seven years, forever broke the political power of Greece. Instead of standing united against foreign foes, the two leading states of Hellas preferred to ruin each other. Yet there was by no means so much at stake in this war as had been the case in the Persian Wars. Hellenic culture, though greatly retarded and hampered by the devastations of this war, and lacking the brilliant inspiration of the Athens of Pericles, went on uninterrupted.

161. The cause of the war was the growing jealousy between Athens and Sparta. Athens had nobly and efficiently championed the interests of Hellas at large, and was now in possession of a well-governed empire. She had gained the power which Sparta had lost through her many blunders. Sparta keenly felt the humiliation. While Athens had risen by her superior intellectuality, Sparta could think of no other means to regain her prestige than war and physical destruction. — As in most wars commercial rivalry came in also. In consequence of the enormous development of Athenian commerce, Corinth had lost nearly all her trade with the Aegean lands, and she foresaw that she would also lose the trade with the western coast of Greece. These are the real reasons for the disastrous war.

162. The Affair of Corcyra. — This city had been founded by Corinth and was now next to it in commerce and naval power. It came to blows with the mother city, and asked to be admitted into the Athenian League. Athens sent a small squadron to its aid. Corinth now complained to Sparta. Negotiations followed between Sparta and Athens. The Corcyra affair fell out of sight. Sparta, with an air of unselfish righteousness, posed as the champion of Hellenic liberty against tyrant Athens, and demanded that Athens “set the Aegean cities free.” Upon the suggestion of Pericles, Athens sent a dignified refusal, which, however, as he plainly told the Assembly, meant war. Thus, in 431 began the Pelo-ponnesian War.

The Corcyra affair was merely its occasion, not its cause. Had there been nothing else, that affair would have been adjusted “diplomatically” by peaceful means. But the political world of Hellas was full of inflammable material, which needed only a spark to be set on fire.

163. THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR consists of three distinct periods: (1) the Ten Years’ War, 431-421; (2) the Sicilian Expedition, 418-413; (3) the Last Nine Years, 413-404. It is impossible to give in our brief synopsis an adequate idea of the deeds of noble patriotism, bravery, and able generalship on the one hand, and on the other, of the mean selfishness, treachery, destruction of property and human life, and of the private and public demoralization which accompanied this suicidal war.

164. The Ten Years’ War. — The Spartans began the war by invading Athens, and forcing the rural population to flee into the city, where they found protection between the Long Walls. They could not prevent the provisioning of Athens by the fleet. The Athenians with their fleet ravaged the coast of the Peloponnesus. This was repeated year after year.

In the second year a plague swept over Greece, which worked a terrible havoc in the dreadfully congested city of Athens. The refugees were living under the most unwholesome conditions. Death raged among them without check. The bodies of dying men lay one upon another. Half-dead creatures reeled about the streets, poisoning all the fountains and wells in their longing for water. The pestilence returned each summer for several years, and destroyed one fourth of the population. The greatest loss it inflicted upon Athens was the death of Pericles, who succumbed to it in the third year of the war, at a time when the Athenians more than ever needed his firm and enlightened guidance. The tanner Cleon, strong-willed, but rude, untrained, and unprincipled, was the chief demagogue who rose in Pericles’ stead.

Sparta now caused much trouble by rousing cities of the Athenian Empire to revolt, while Athens lost much sympathy by brutally punishing those it had reconquered. Then Sparta sent a powerful army under an excellent general to the coast of Thrace, and an Athenian force, led by Cleon, was decisively defeated. Cleon himself was among the slain. The Spartans also suffered much from the war. So, in 421 a peace of fifty years was concluded by which everything was restored as it had been before the war.

165. The Sicilian Expedition. — By this time Alcibiades, a young man who combined a brilliant eloquence with a great power of leadership, had attracted the attention of the Athenians. Alcibiades wanted war to gain renown. He induced the Athenians to send help to some little states in Sicily which were threatened by the mighty city of Syracuse. Alcibiades was one of the commanders. In his absence he was accused by influential enemies of a crime which would be punished with death. When he became aware of this, he left the Athenian armament, fled to Sparta, and prevailed upon the Spartans to break the peace they had concluded, and send assistance to Syracuse. The Athenian expedition, owing partly to bad generalship, became a complete disaster. Two hundred fine ships and forty thousand men, among them eleven thousand Athenian hoplites, were lost.

166. The Last Nine Years. — Upon Alcibiades’ suggestion, Sparta sacrificed the Asiatic Greeks to obtain the assistance of the Persians. Fleet after fleet was built for Sparta by Persian money. Persian satraps appeared again in the Greek cities of Asia Minor. In spite of several brilliant victories, the war now turned against Athens. At Aegospotami (Goat Rivers) the Spartan general Lysander completely defeated the Athenians, had 4000 prisoners executed, and sailed to Athens; after a terrible siege, the proud city surrendered in 404 B.C.

167. “Peace.” — Corinth and Thebes demanded that Athens should be destroyed. But Sparta would not lose her as a check upon these cities. The Athenian Empire was at an end, however, and to the music of Peloponnesian flutes the fortifications of the Piraeus and the Long Walls were demolished. The cities formerly under Athens now passed under the political control of Sparta and Hellas was declared free.

SPARTAN SUPREMACY

168. Spartan Rule. — Sparta, now mistress of Greece more completely than Athens had ever been, followed her old methods. In the cities which she had “freed” from the “tyranny” of Athens, she abolished the democracies and set up boards of ten oligarchs with full power. A Spartan garrison under a “harmost” assisted them in their work of oppression, plunder, and murder. The tribute formerly paid to Athens was doubled.

During the last years of the Peloponnesian War an attempt had been made in Athens to restore the power of the aristocrats. The Assembly, no longer controlled by men like Pericles, had shown itself unfit to deal with matters of war and foreign relations, which require secrecy and prompt action. The aristocrats formed a Council of Four Hundred, which, however, showed itself as incompetent as the Assembly had been, except in murder and plunder. It was soon overthrown, and the old democracy restored. After the victory the Spartan conqueror established a board of thirty, called the “Thirty Tyrants,” with absolute power. This reign of terror lasted only one year. In spite of Spartan protection, the Thirty were overpowered by the democratic party under the leadership of Thrasybulus. The restored democracy showed itself remarkably moderate, punishing only a few of the most guilty of the Tyrants, and granting for the rest and their adherents a general amnesty. This procedure contrasted so favorably with the cut-throat rule of the Four Hundred and the Thirty, that Athens was undisturbed in future by revolution. In other parts of Greece the people were not so fortunate. Democracy never again was so general in Hellenic cities as it had been before the Peloponnesian War.

169. The “End” of the Persian Wars. — Inspired by her noble king Agesilaus, Sparta again opened hostilities against Persia. She sent an army to Asia Minor, to carry the war into the enemy’s country. Agesilaus made rapid progress. But enemies arose at home. Thebes, Corinth, Athens, and Argos combined against Sparta. The victorious Agesilaus had to return. Conon, an able Athenian general, who had entered Persian service after the downfall of Athens, and was now admiral of the mixed fleet, destroyed the Spartan fleet. He then sailed home and with Persian money restored the fortifications of his native town. After a few years of fighting, Sparta, in 387 B.C., asked Persia to act as arbiter, which meant that the Great King was to dictate the terms of peace. The Greek cities on the shore of Asia Minor he gave to himself; the islands of Lemnos, Imbros, and Scyros to Athens. All other Greek cities were to be independent, that is, all leagues among them were dissolved, so that Sparta was in a position to deal with them individually.

Thus the tottering Persian Empire won back by Greek disunion and treachery what she had lost a century before through superiority of Greek arms. Besides Persia, the Spartans were the only gainers. Rightly or wrongly they retained the power over the Peloponnesian League, and also began to act as the king’s police commissioners with power to see to it that the terms of the peace were carried into effect. With her brutal cunning she prevented the rise of any state to a position in which it might be dangerous to her. She did not shrink from interfering even in the interior affairs of other states.

170. Thebes’ Brief Supremacy. — The high-handed manner in which Sparta interfered in the affairs of Thebes roused that city to a determined resistance under an able leader, the noble-hearted Epaminondas. By his superior generalship Epaminondas defeated the Spartans and their allies in the battle of Leuctra with terrible slaughter. A number of Greek states allied themselves with the victorious Thebans, whose influence reached as far as Macedonia. For nine years, as long as Epaminondas lived, they maintained their position as the foremost state of Greece, though many other cities, such as Athens, refused to join them and even worked against them. The man who had raised Thebes to the height of its power, Epaminondas, fell in the battle of Mantinea, in which he had just inflicted another defeat on hitherto unconquerable Sparta. His death ended the supremacy of Thebes.

After a short period of partial unity the Greeks had shown that with their undying jealousies and narrow local patriotism they were unable ever to form a united powerful nation. They needed to be welded together by some outside power. In culture, in all kinds of art, Greece remained the teacher of mankind. The very men who were to conquer her politically were also to lead her forth upon her mission of enlightenment, and to secure universal recognition of her intellectual supremacy.

THE MACEDONIAN CONQUEST

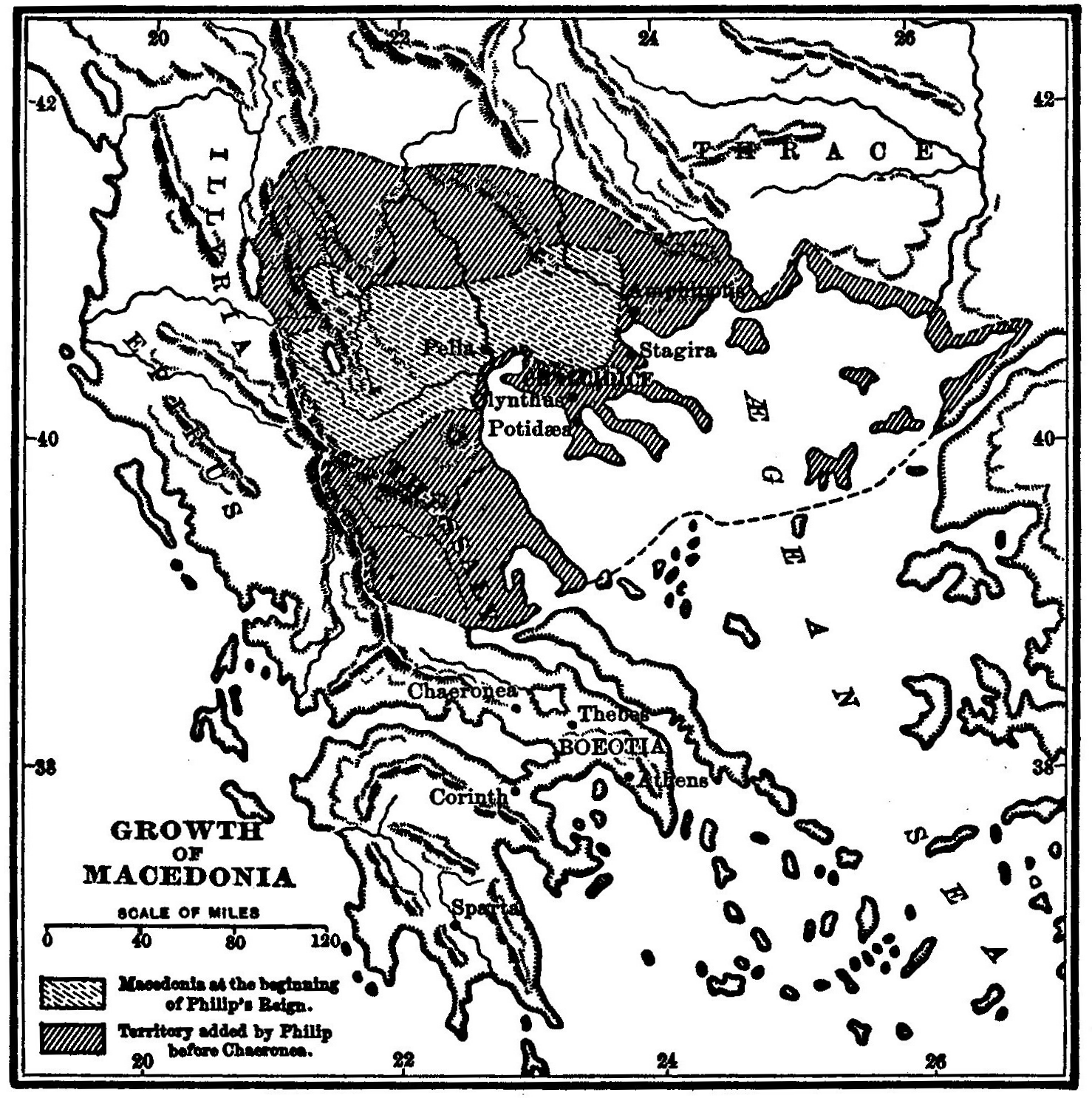

171. Philip II of Macedonia. — At the time of the Persian Wars Macedonia was still a little-known country. It had some good rulers. But the one who rapidly led it to prominence was Philip II. Philip had spent some years as hostage at Thebes (§ 170), where he had the best chance to learn the good and bad features of the Greeks. He was ambitious, crafty, an unfailing judge of character, a marvelous organizer, and a first-class general. He made it his aim to become the head of all Greece, and with the Greek soldiery to enter upon a gigantic career of conquest. His acquisitions (see map) gave to his country good harbors and gold mines which enriched his treasury. He improved on the Greek methods of warfare. He gave his hoplites spears which were eighteen feet long. In battle the first several ranks passed their spears between the men before them, so that five rows of bristling spearpoints projected beyond the first soldier.

172. Philip II and the Greeks. — He knew how to play one Greek state against the other. One of his principles was, “No city wall is so high that a donkey with a load of gold cannot jump over it.” He had paid agents among the pretended patriots of all Greek states. He posed as defender of Greek liberty, even of Greek religion.

At Athens Demosthenes, the greatest orator the world has ever known, displayed all the force of his wonderful eloquence to rouse the people against the encroachments of Philip II. Most of his speeches, unsurpassed masterpieces of oratory, fell on deaf ears. But at length the Athenians united with the Thebans, so often their deadly foes, against the ever increasing power of the northern monarch. They were hopelessly crushed at Chaeronea, 338 B.C.

173. Greece under Macedonia. — Chaeronea has been called the end of Greek liberty. It certainly was the beginning of Greek unity. Philip carefully avoided the appearance of a brute conqueror. At a congress of all the Greek states at Corinth a kind of constitution was adopted, according to which Greece united under Philip II. Every state was independent in its own interior affairs, while Philip would take care of all international relations, including the question of war and peace. He was elected as generalissimo for the war soon to be undertaken against Persia. Thus Greece became a highly privileged province of the Kingdom of Macedonia, and until 1829 A.D. remained the province of some other state.