There is a satanic quality to the French Revolution that distinguishes it from everything we have ever seen or anything we are ever likely to see in the future. Recall the great assemblies, Robespierre’s speech against the priesthood, the solemn apostasy of the clergy, the desecration of objects of worship, the installation of the goddess of reason, and that multitude of extraordinary actions by which the provinces sought to outdo Paris. All this goes beyond the ordinary circle of crime and seems to belong to another world.[1]

The Catholic writer Joseph de Maistre wrote these words after living through the French Revolution and seeing its effects. If he could look into the future, perhaps he would acknowledge that events to come could have greater satanic qualities. This French Revolution did, however, begin the process of turmoil and rejection of the past that swept across Europe and the world in the following centuries.

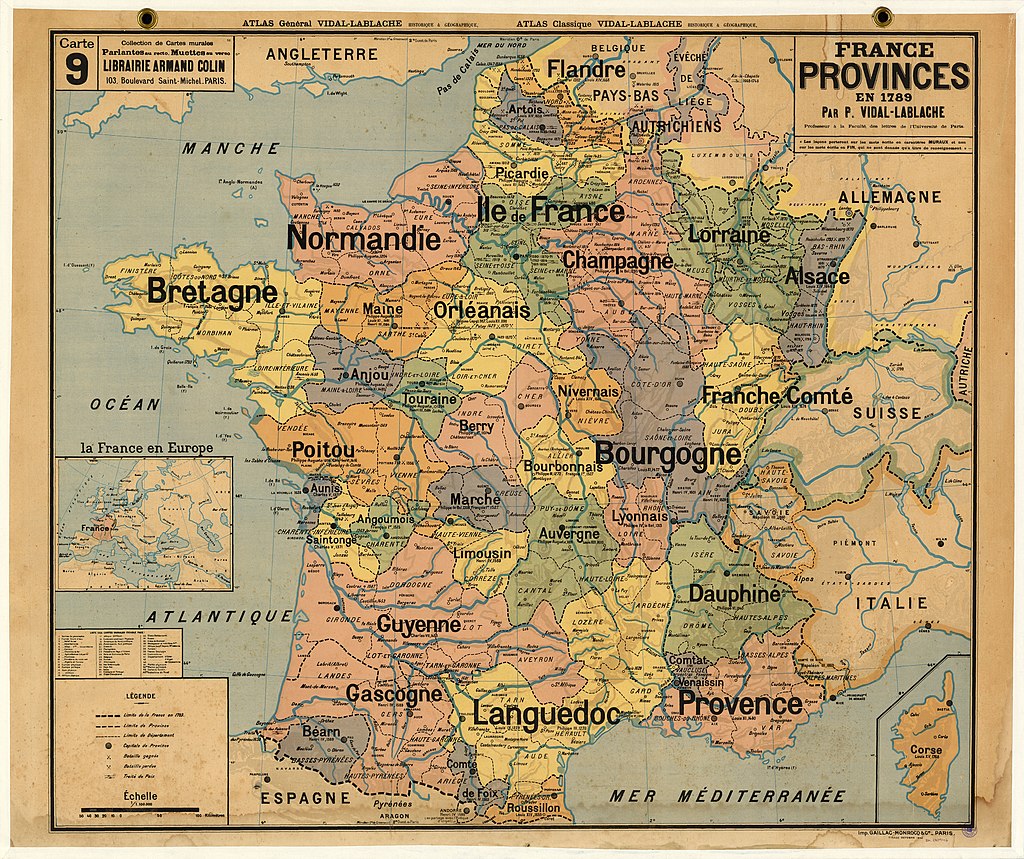

France before the Revolution was much like other countries of Europe. It had a king, a society based on the feudal system, and a largely agrarian population. It was a Catholic state. The government in France was very centralized, especially in the century leading up to the revolution.

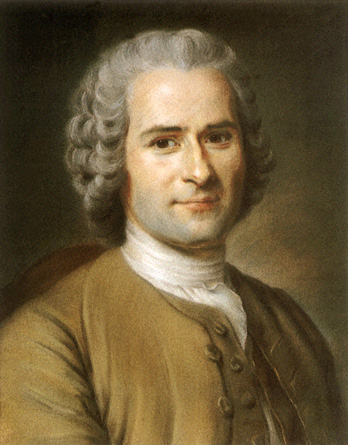

There are many things to consider when studying the French Revolution. Of course, this brief overview cannot touch on all of them, but it will cover the basics. Firstly, we need to understand what society was like at the time. The monarchy was absolute. The majority of the population were peasants. The middle class was especially influenced by the Enlightenment ideals of Rousseau and other philosophes. The Church collected tithes, and for the most part the higher clergy lived in luxury while priests barely got by. Generally, the Church and nobility did not pay taxes so this burden fell mostly on the middle and lower classes. Also, the feudal system was outdated and put excessive burdens on the lower class. Finally, France was on the verge of bankruptcy.

There were three French kings during the 18th century. Louis XIV (1643-1715), Louis XV (1715-1774), and Louis XVI (1774-1792). Therefore, there were only three kings over the course of just 149 years.

These kings spent billions of dollars on credit. They ruled France from Versailles, an opulent palace built by Louis XIV. It was incredibly costly and overburdened the royal income. The royal household had more than 15,000 people living there in great luxury. War, however, was the greatest royal expense of those days and Louis XIV worked tirelessly to expand France’s power and its borders. At the end of his reign, more than half of France’s income went to paying the interest for the debts he created.

Louis XV lacked the strong character of his predecessor and was openly immoral. He preferred to live a luxurious life at Versailles while letting ministers manage the affairs of state. He brought greater financial strain on France with the Silesian War and Seven Years’ War.

King Louis XVI was a moral person who loved his wife, Marie-Antoinette, and had a good heart. He was, however, weak-willed and very indecisive. He inherited an enormous debt and added to it, especially by aiding the American colonies in their war for independence.

These kings ruled in a similar absolute manner. Louis XIV ensured that the nobility did not have the power they had during the feudal days. Instead, they mostly lived at Versailles, fighting over who would win the king’s favor. If they did return home to their estate, it was usually to get more money to continue living a life of luxury. The nobility did not govern, instead the king had his own representatives in the various provinces of France. The very purpose of nobility was being gradually lost.

French society at that time was divided into three official groupings called estates. The First Estate was the clergy, the Second Estate was the nobility, and the Third Estate was everyone else, including the middle and lower classes. The clergy did not pay taxes to the government (aside from a “gift” every few years). The Church did, however, provide society with services including healthcare and education. The nobles were also exempt from taxation or found ways to get around it. During feudal times the nobility had provided society with protection and security, but by the late 1700s their original purpose for tax exemption seemed to be entirely outdated. This left the tax burden mostly on the Third Estate.

The Third Estate had to pay a land tax, feudal dues, church tithes and other taxes that together could amount to nearly 80% of their income. The most hated tax was levied on salt and varied from city to city. For example, the same amount of salt could cost seven francs in one place but 28 francs in another. Leftovers from the feudal era also meant that the peasants had to work for a time without pay on public roads even during harvest time at the expense of their own crops.

The burdens on the Third Estate seem great by today’s standards, but if we compare them with other parts of Europe such as in Poland or Germany, the peasants lived similar lives. So why is it, then, called the French Revolution and not the German Revolution or the Polish Revolution? The answer is complex of course, but France was the heart of new revolutionary ideas that rocked the very foundations of society. It was these “enlightened” ideas that motivated those who put the Revolution in motion.

The Enlightenment thinkers were rationalists, or “freethinkers,” those who thought they should be free to think as they wished in the pursuit of truth. Writers such as Voltaire and Diderot fought to discredit the Church and the principles of Christianity. Rousseau popularized the notion that the existing governments at the time were illegitimate and that the only legal government is formed by the “will of the people.” For him, if there were rulers, they would get their power from the people and not from God. The government of France tried to suppress erroneous writings, but the secrecy of the Masonic lodges of France allowed these ideas to spread freely.

The Church in France wasn’t all bad in those days, but it was weak in fighting these new ideas. It had become somewhat separated from Rome by Gallicanism which nearly made the Church in France independent. In some ways this was a reality, especially due to the fact that the king had a great deal of control over it. The higher clergy were chosen by the king and mostly came from the nobility. Oftentimes these noblemen were forced by norms of the day to become bishop or abbot, so they cared very little for their sacred duties and rather cared more for pleasures and riches. The priests of the day were poorly-educated and lived very poor lives. These, as well as internal disputes in the Church in France, tended to discredit it. Finally, Jesuit education centers were of huge importance in teaching sound doctrine, but they had been expelled from France in 1764 and finally suppressed by Pope Clement XIV in 1773.

The financial situation when Louis XVI came to the throne was serious. He had to do something immediately, and appointed several finance ministers in succession in an attempt to bring the debt under control. The country was effectively bankrupt by 1781. Among other reforms, each minister came to a similar conclusion that the French nobility should pay taxes. Whenever this ultimatum was presented to the nobles, however, they soundly resisted and Louis would give in. By 1786, interest on the debt was about half of the royal income per year.

Louis needed more money by taxing the nobility and he knew he had to get it somehow. He finally tried to pass a royal edict to get it done. To become law, however, the edict had to be registered by the Parlement of Paris; and members of this body were nobility so they made the excuse that it could not be registered because only the Estates-General had the power to impose new taxes.

The Estates-General was a meeting of representatives of the three estates. It was supposed to be an advisory body and was not necessary for the king to govern France, so it had not been called to meet since 1614. Louis gave in and called the Estates-General on August 8, 1788 and recalled Necker as finance Minister. He set the meeting for 1791, hoping that the debt problem could be solved by then.

Normally, there would be 300 members elected from each estate from across France. This time, Louis made the fateful decision to accept the Third Estate’s request to have 600 members, making it equal in number with the other two estates. This did not seem to matter because each estate received one vote. The clergy and nobility usually voted together so they would still have a 2-1 lead over the Third Estate. Recall, however, that Louis wanted the Estates-General to approve his new taxes, so perhaps he thought that the additional numbers in the Third Estate would somehow help him. In fact, it was the equal number of Third Estate to the combined first and second estates that allowed the Revolution to begin as it did.

In preparation for the Estates-General, the king requested recommendations from the three estates called cahiers. These teach us much about France before the Revolution. They show that the king was supported and that there was no apparent wish to end Church influence in France. The first two estates had many members that were willing to make concessions and pay taxes. Enlightenment ideas were found among the cahiers of the First and Second Estate, but especially with the Third Estate which supported constitutional monarchy, equality for classes, freedom of press, and the notion of the social contract. About two-thirds of the Third Estate was made up of lawyers, a group that was very fond of the Enlightenment ideals.

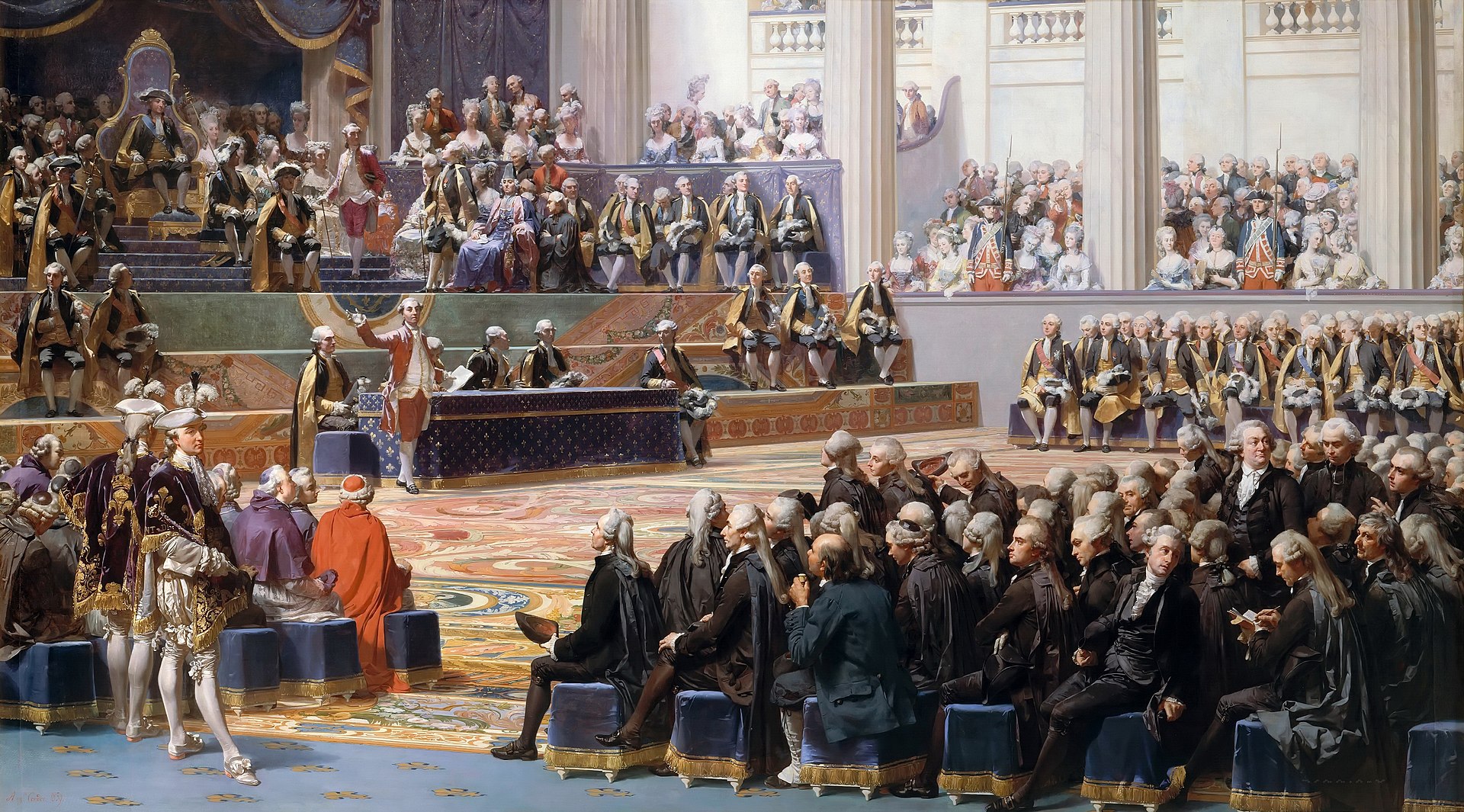

The debt crisis forced the king to convoke the Estates-General early, so it met on May 5, 1789 at Versailles with full royal splendor and with the ceremony of the Catholic Church. The first order of business was to establish voting rules. The Third Estate seized the opportunity and demanded that the three estates vote together as one assembly. The king delayed his decision for five weeks.

In the meantime, rumors of famine threatened France. The previous summer of 1788 had a drought and the winter that followed was the coldest France had seen in 80 years. There were spring floods and another drought forebode bad harvests for 1789. The people of France were fearful. There was unrest, anxiety, and fear of economic recession. The public was aware of the near-bankruptcy of France and they thought the Estates-General would somehow fix everything.

It was a Liberal priest and deputy for the Third Estate, Abbe Sieyes, who made a motion on June 10 to invite the other two estates to join the Third Estate’s roll call. Of course, this would effectively eliminate the votes for the first two estates. Only three clergy joined, but not one nobleman.

Then on June 17, the Third Estate made its true position known and declared that it represented ninety-six percent of France and thus represented the majority, and their decisions would express the will of the people. Upon this authority they formed the National Assembly, claiming sovereign power. The king did not use force to stop this revolution. Instead, he called a royal session for June 22. In the meantime, the Third Estate wanted to use the hall on June 20, but guards said the building was being prepared for the royal session and they couldn’t use it. Therefore, the Third Estate met in a nearby tennis court and it was here that they swore to never separate until they had formed a constitution for France.

Louis tried to negotiate with the Third Estate but to no end. They claimed to be the sole representatives of the people. Over the following days, members of the clergy and nobility joined the Third Estate. The king gave in to defeat and on June 27 ordered the three estates together, forming the official National Assembly.

Secretly, Louis was now planning to stop the revolution by force and began drawing German and Swiss mercenaries around Paris and Versailles. He could not rely on the French Guard which had been undermined by Louis Philippe, Duke of Orleans, who hoped to take the throne from the king. The Duke’s magnificent residence had in fact become a place of secret meetings filled with intrigue, sedition, and immorality.

The National Assembly warned the king to withdraw the troops, but he refused. His response was to dismiss Necker as finance minister on July 11. This angered the people of Paris, and the electoral college of Paris that had chosen the deputies for the Estates-General took command of the growing mob. Revolution was in the air. They took a cannon, ammunition, and arms from the government’s arms depot and prepared to fight.

On July 14, the revolutionary forces attacked the Bastille. This was an impregnable fortress used to hold prisoners of the king. In those days, anyone could be held without warrant as prisoner by the will of the king, so the mob attacked the prison hoping to free these poor political prisoners, but instead they found only a few criminals being held. The Bastille guard of little more than 100 men surrendered, being promised safety. The promises were in vain though and the mob killed several, parading the Bastille governor’s head on a pike through the streets. This day is celebrated as France’s Independence Day.

Louis now began giving in to demands. He restored Necker. He allowed the Paris electors to remain in control and form a city government and armed militia that they called the National Guard. This newly-created army was placed under the command of the marquis de Lafayette who had helped America during its war for Independence. Then Louis XVI made a show of solidarity with the revolutionaries, entering Paris on July 17 wearing a hat with the tricolor – the colors of the revolution.

France was now in a state of anarchy. Who was in charge? The king? The National Assembly? Local officials did not know the answer and stopped enforcing the law. People stopped paying taxes. Many cities throughout France then set up municipal governments, often formed by the same electoral colleges that had voted on representatives for the Estates-General. In much of France, however, chaos reigned. Peasants burned chateaux of their lords, they attacked monasteries and the homes of bishops. In cities, workers rose up against the bourgeoisie. These troubles made the threat of famine a reality.

Uprisings across France led the National Assembly to abolish special privileges which the nobles and clergy eagerly gave up on August 4. In a single night, they abolished the feudal system along with church tithes. All this happened in just three months since the Estates-General first met.

A financial crisis thus brought about the destruction of the ancient regime, as the political and social system of France was called prior to the French Revolution. There were many factors in play, though. Enlightenment ideals motivated representatives of the Third Estate to conspire to overthrow the king’s power. They came to the Estates-General with a plan, although how well thought-out is unknown. The Duke of Orleans played a notorious role in the whole affair, but once again, his role is shrouded in secrecy. The desires of the representatives for the Third Estate, however, were made clear. They wanted equality and the establishment of Rousseau’s ideal government. The suddenness with which they made this happen is mind-boggling.

The king went into the first meeting of the Estates-General hoping to get taxes from the nobility and walked out facing a stalemate with the Third Estate. What could he have done? Could he have stopped the revolution by forcing strict rules on the Estates-General from the very beginning or by using force early on? There is no way of knowing, of course, since he gave in to every demand of the Third Estate and was left the symbolic head of the National Assembly. That assembly went on to make changes to France that Louis and his predecessors could never have dreamed possible.

[1] The Old Regime and the French Revolution, 448.

Bibliography:

Betten, Francis Sales. Ancient and Medieval History from the Origin of the Human Race to the End of the Religious Unity of Europe. Allyn and Bacon, 1944.

Carroll, Warren H. The Revolution Against Christendom: A History of Christendom, Vol. 5. Christendom Press, 2005.

Herbermann, Charles George. The Catholic Encyclopedia; an International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church. Vol. 6. New York, The Encyclopedia Press, 1913.

The Old Regime and the French Revolution. Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press, 1987. http://catalog.hathitrust.org/api/volumes/oclc/81999319.html.

Zehnder, Christopher, Ed. “Light to the Nations 2 – Making of the Modern World.” Catholic Textbook, 2017.