The following is an excerpt (pages 112-117) from Ancient and Medieval History (1946) by Francis S. Betten, S.J. Although some information may be outdated, the Catholic historical perspective it provides remains pertinent. Use the link at the bottom of post to read the previous/following pages. Use the Search box above to find specific topics or browse using the Resources tab above.

CHAPTER XII

ATHENIAN LEADERSHIP FROM THE PERSIAN WARS

TO THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR

BEGINNING AND GROWTH OF THE ATHENIAN EMPIRE

131. Athens Fortified. — If Athens was the soul of the Greek resistance against the Persians, Themistocles was the soul of Athens. He had started and guided its actions. To him it was due that Athens possessed the fleet, without which the naval power of all the rest of Greece would have been helpless (§ 121). He now continued his policy. Athens needed city walls. Themistocles persuaded the people to commence their building even before they had restored their own habitations. He knew that Sparta would oppose this move, because she wanted no fortifications outside the Peloponnesus, and that she might even use force to prevent the construction. So the Athenians worked with feverish haste, everybody — men, women, children, and slaves. No material was too precious. Stones were taken from the temples, monuments from the burial grounds. To gain time and hoodwink the Spartans, Themistocles had recourse to wiles. (See Ancient World, § 184.) He succeeded. The city walls of Athens were finished, to the discomfiture of Sparta and other jealous cities, before anybody could interfere.

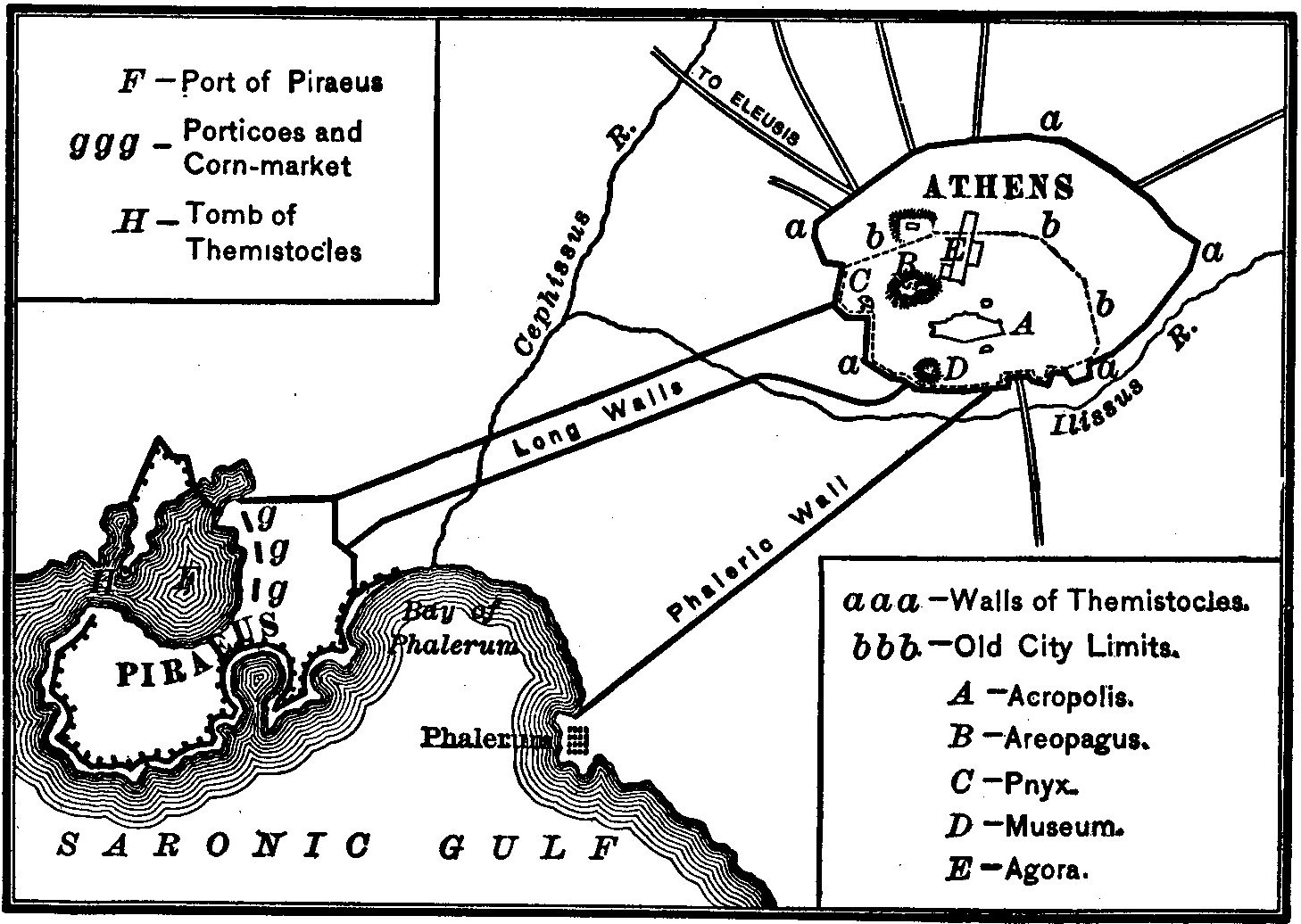

132. The Piraeus. — Themistocles was not yet content. Athens lay some three miles from the shore. Originally Athens used as a harbor the open roadstead of Phalerum, but shortly before the Third Persian War, when Athens was building its fleet, Themistocles had also taken care that the smaller bay of Piraeus be improved. This gave the city a much better harbor. Now he insisted that it should be fortified, so that in case of an attack by sea it could be easily defended. This was done in such a way that Athens now possessed two walled cities, each four or five miles in circuit, and some four miles apart. At the same time the building of twenty ships every year was to go on. The excellent harbor with its facilities and its security at once brought back the throngs of alien merchants who had fled before the Persian attacks.

ATHENS AND ITS PORTS

133. The Double Battle of Mycale. — The union of all Greek states under the leadership of Sparta still continued. In 479 a Greek fleet under a Spartan admiral crossed the Aegean Sea. On the very day on which the Persian army was annihilated at Pla- taea, these forces won a double victory at Mycale, one on sea and one on land. This was the signal for the Ionian cities to revolt against Persia. But the Spartan admiral refused to come to their aid. When the Athenians, to whom belonged three fifths of the fleet, insisted on supporting the Ionians, the Spartans sailed away, leaving the Athenians to assist the Ionians as best they could. Joyously the Athenian contingent undertook the task.

134. Athens Becomes Head of the League. — The next spring the Spartans thought better of the matter. Unfortunately for them, they sent as admiral Pausanias, who had commanded at Plataea, and who now, proud of that glory, treated the allies with haughty contempt. He was recalled, accused of treasonable negotiations with Persia, and condemned to death. The allies, however, refused to accept another commander from Sparta. Thereupon Sparta and the Peloponnesian league (§ 114) withdrew entirely from the alliance and took no further part in the war against the common foe. Thus Athens rose to the leadership.

135. The Confederacy of Delos. — The alliance, now freed from the discordant element of the Spartans, organized along more definite lines. Each member was to contribute a certain number of ships and a certain amount of money every year. Athens, which furnished overwhelmingly the largest number of ships, was to be the leader to appoint the admirals and generals, and to preside in the yearly congresses in which every city (or island), large or small, had one vote. The congress was to be held and the common treasury located on the island of Delos. Aristides was appointed to fix both the number of ships and the fees for each individual city, and he delivered himself of this honorable duty to the full satisfaction of all concerned. His tact, courtesy, and unselfishness contributed greatly to make the idea of this new league generally popular. The Confederacy of Delos consisted mainly of Ionian cities and islands, which were principally interested in commerce and navigation. It thus contrasted with the Spartan inland league of the Peloponnesus.

The chief military hero was Cimon, son of Miltiades. (See D. R., I, No. 74.) He cleared one island and city after another of the Persian garrison, until the whole region of the Aegean Sea was free. In 466 he even went beyond the Aegean and defeated the Persians completely in the large battle on the Eurymedon in Pamphylia. The confederacy grew rapidly. At one time it is said to have embraced about a thousand cities.

136. How the Confederacy Became an Empire. — Soon some cities preferred to pay money rather than furnish warships. Nor did many care to be represented in the congresses. The Athenians were highly pleased with this change of things. It left the control of all affairs entirely to them. Here and there cities refused to contribute at all. They forgot that the Aegean remained free of the Persians for no other reason than because it was patrolled by the Athenian fleet. Athens looked upon these delinquents as rebels, sent its warships against them and reduced them by force to “obedience.” It took away their fleets, dismantled their fortifications, and forbade them to conclude treaties of any kind with any other state. Before long even the loyal cities found themselves treated as subjects. The treasury was transferred from Delos to Athens; the courts of the cities were made subject to the Athenian courts, and the Athenian Assembly managed all affairs without consulting the cities. However, Athens continued to perform faithfully the work for which the original confederacy had been created. It kept the Persians out of the Aegean, and assisted the people of the various cities in maintaining democratic constitutions against aristocratic and oligarchic tendencies. Thus the Confederacy of Delos had become an empire with Athens for its dominant state. The islands of Lesbos, Chios, and Samos were the only ones that had not become subject states.

FIRST PERIOD OF STRIFE BETWEEN ATHENS AND SPARTA

137. Beginnings of the Quarrel. — The island of Thasos revolted against Athens and applied to Sparta for help. While the Spartans armed secretly with a view of invading Attica, an earthquake destroyed part of Sparta and threw the whole of Laconia into confusion. The Helots and Messenians seized the opportunity and rose so formidably that the Spartans even cried to Athens for assistance. Prompted by Cimon the Athenians dispatched an army. When it arrived, the Spartans had changed their mind. Without any reason they suspected it had come to aid the Helots, and sent it home with insult. This roused great indignation at Athens. Cimon was ostracized. His place as the most prominent citizen was taken by Pericles, one of the greatest statesmen of all times.

The insurrection centered around the fortress of Ithome in Messenia, which the Spartans were unable to take. They finally allowed the inhabitants of Ithome to leave it unmolested and to emigrate. Athens gave them the city of Naupactus which had just been conquered and thus gained a new and faithful ally.

138. Hostilities. — Pericles endeavored to win allies in continental Greece in addition to the maritime empire. Thessaly, with its excellent cavalry, and Megara, which held the key to the isthmus, and other states really joined Attica. The war against the Persians was by no means forgotten. An enormous armament, consisting of 250 vessels and some 40,000 soldiers and sailors, sailed to Egypt to assist that country in a revolution against the Great King. The enmity with Sparta now became open war. An Athenian fleet surprised the Laconian dockyards and gave them to the flames. Pericles began setting up democracies in the towns of Boeotia. Sparta sent an army for the protection of the aristocrats, which won one battle and was decisively beaten in a second. At the same time the Athenians had a war on hand with Aegina and Corinth, both of which had lost much of their trade after the establishment of the Athenian Empire. Then came the stunning news that the whole armament sent to Egypt was entirely destroyed after great initial successes. Euboea revolted. Megara fell away and joined the Peloponnesian League. In Boeotia the aristocrats got the upper hand, and that country was lost for Athens. It is most remarkable how, in spite of such blows, the Athenians could keep up their buoyant spirit. They conquered Aegina and destroyed its fortifications. By skillful and energetic movements Pericles forced a Spartan army, which had invaded Attica, to withdraw without a battle. He then reconquered Euboea and settled there a new contingent of cleruchs (§ 107). During this period of storm and stress, Athens completed her fortifications by building the “Long Walls” which connected the Piraeus with the city. (See map on page 113.) They made Athens absolutely safe for a siege, as long as she kept her supremacy on the sea.

139. Thirty Years’ Peace. — Both parties were tired of war. In 445 Pericles negotiated a peace of thirty years with Sparta. Athens had lost most of her allies in central Greece, but retained her entire maritime empire. The peace, which was really not more than a truce, lasted fifteen years, which was a time of blessing for Athens.