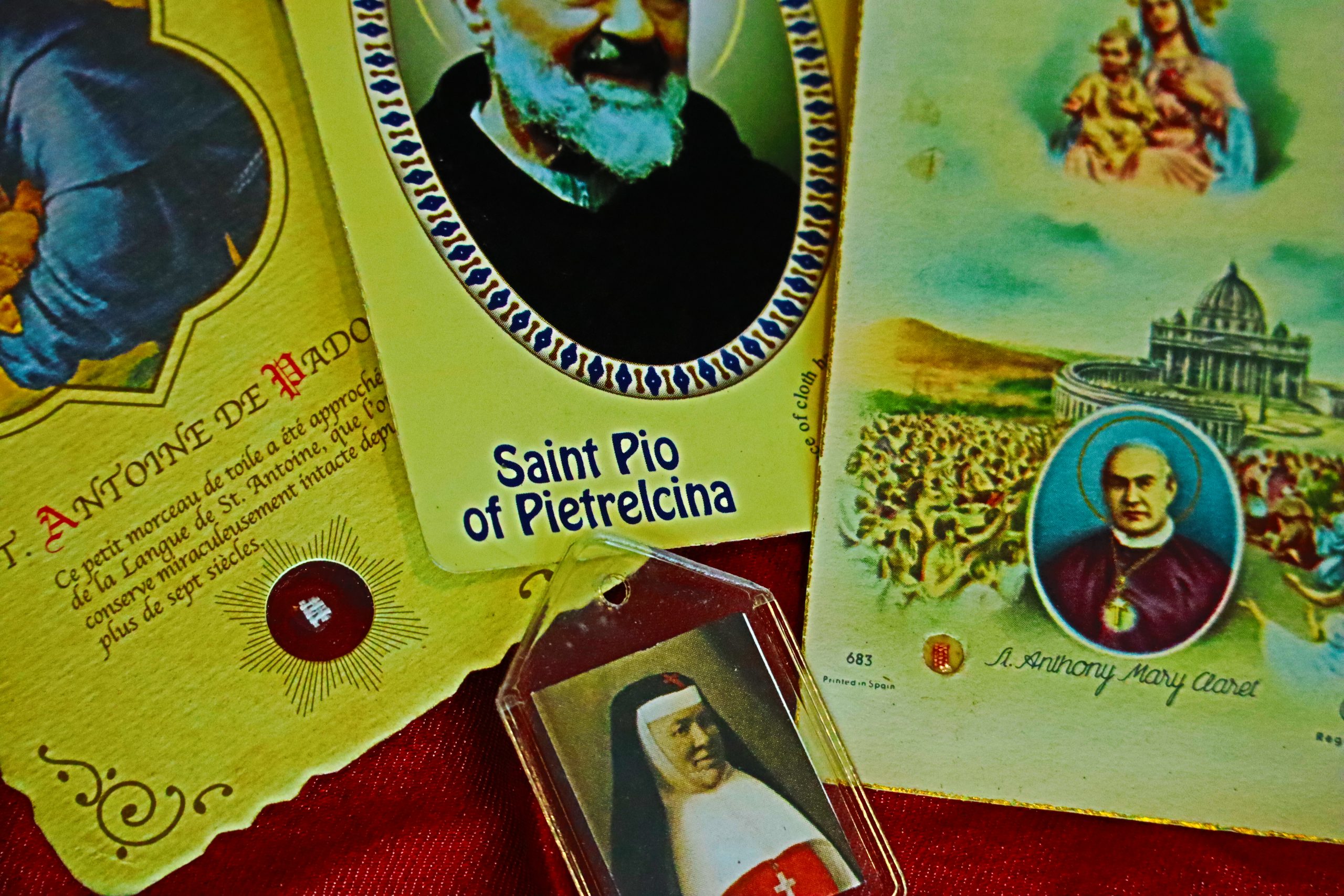

St. Anthony’s Chapel in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania holds more than 5,000 relics and claims to be the largest collection of holy remains in the world except that found in the Vatican. Not all churches have as many relics, but relics are an important part Catholic tradition. They are prominently venerated in churches throughout the world. They are placed inside of altars. They are found in private homes. They are inserted into countless holy cards, medals, and reliquaries. Far from being a curious practice of the Middle Ages, the veneration of relics continues as a vibrant part of the Catholic spiritual life today.

Many people today, even Catholics, get a bit confused over what relics are and even what the whole point is about them. So, what are relics and why are they significant? Simply speaking, a relic is something remaining from a previous time period. The Catholic relic, however, is more than just remains – it is holy. There are three degrees of holy remains.

First class relics are any parts of a saint’s body as well as the objects directly connected with the life of Christ and His Passion.

Second class relics are clothing or other things that came into physical contact with the saint while he or she was alive on earth.

Third class relics are those which have touched a first- or second-class relic. Cloth that has touched the bones of a saint is called brandea and is a third-class relic.

It is common for humans to keep relics. Even in the secular realm devotees of Elvis Presley, or other celebrities, do just this. We hold on to possessions and pictures of relatives who died decades ago, mementos from special events, and other random knickknacks. St. Thomas Aquinas recognized that the natural affection people have for one another causes them to venerate external things that a person owned in addition to the body itself. Yet, even greater respect for the body arises because one day it will resurrect with the soul. Add to that the holiness of sainthood and the body becomes something to be venerated and treated with the utmost respect. The body of a saint who lived and died participating in the very life of God makes us wish to be close to these holy relics, and through the communion of saints we on earth are united with those in heaven. God distributes many graces and miracles through these relics.[1]

We need to keep in mind, however, what veneration is not. The veneration of saints is not the worship of latria which is directed towards God. It is instead a veneration of the material objects of the cult such as bones, ashes, clothing, etc, although as the Catholic Encyclopedia says, this veneration “does not rest in them, but looks beyond to the saints they commemorate.”[2] St. Jerome puts it very well explaining, “We do not worship, we do not adore [saints], for fear that we should bow down to the creature rather than to the Creator, but we venerate the relics of the martyrs in order the better to adore Him whose martyrs they are.”[3]

Respect towards relics is not something unique to Catholicism, nor was it invented in the Middle Ages. For instance, the ancient Greeks honored the bones of their heroes. Relics of Buddha, such as bones, teeth, and hair are in pagodas and are worshipped throughout the Buddhist world. The relics of Confucius are likewise venerated by millions who offer homage at his tomb. Islam reveres two hairs of Mohammed which are kept in Jerusalem at the Dome of the Rock Mosque. These and many other examples attest to the prevalence of relics among various times and civilizations.[4]

Relics are also found in the Bible. For example, in the book of Kings we read about a dead body being accidentally put into the sepulcher of Eliseus and it immediately came back to life upon touching the prophet’s bones (4 Kings 13:21, Ecclus. 48:14). The cloak of Christ healed a woman of hemorrhage by her simply touching it (Matthew 9:20-22). Handkerchiefs and aprons were touched to St. Paul and brought to cure the sick who had both disease and evil spirits leave them (Acts, 19:12).

Relics are also found in the Bible. For example, in the book of Kings we read about a dead body being accidentally put into the sepulcher of Eliseus and it immediately came back to life upon touching the prophet’s bones (4 Kings 13:21, Ecclus. 48:14). The cloak of Christ healed a woman of hemorrhage by her simply touching it (Matthew 9:20-22). Handkerchiefs and aprons were touched to St. Paul and brought to cure the sick who had both disease and evil spirits leave them (Acts, 19:12).

The history of relics after the time of Christ is first recorded in a letter dating from about AD 156, the year following St. Polycarp’s martyrdom. In a beautiful passage the author writes, “We took up his bones which are more valuable than precious stones and finer than refined gold, and laid them in a suitable place, where the Lord will permit us to gather ourselves together, as we are able, in gladness and joy and to celebrate the birthday of his martyrdom.”[5] St. Polycarp was consecrated the bishop of Smyrna by St. John the Apostle and the connection is important since it gives a direct lineage of relics to the earlier Apostolic times. These words represent the common Catholic sentiment towards relics even in the earliest Christian era. Pope St. Anicetus (reigned c. 152-160) built a shrine to St. Peter the Apostle where pilgrims visited regularly. St. Paul also had a shrine. Their relics and those of other saints at the time were referred to as tropaion, or in other words, trophies or victory monuments.[6]

The use of relics in the Catholic liturgy has its origins in the underground caverns of the catacombs which served as burial sites for early Christians of Rome and also places to secretly hold religious worship during times of persecution. The custom of putting relics in altars started here with the Mass being offered on the tombs of martyrs. But with Constantine’s Edict of Milan in 313, Christianity was legalized, enabling the cult of the saints and relics to flourish openly. The translation of saints became common during this time. This is the formal removal of the relics from the tomb to a church or chapel which then became a shrine. The translation of a saint is an important part of developing devotion to that saint, and the day on which it occurred is often celebrated as the saint’s feast day. Even today, this opening of the grave and moving the remains of a candidate for the sainthood is part of the canonization process.[7]

The catacombs were no longer used for burial in the 300s, so they became pilgrimage destinations. This changed by the 700s, when age caused them to be dangerous and they were also inconvenient due to the growing numbers of pilgrims so the popes authorized the translation of more relics to churches in Rome and even to other countries.[8]

We don’t know exactly when the practice of venerating very small particles began, but it was widespread in the early fourth century. One altar stone dating from AD 359 has a cut out cavity for containing a relic of the Cross as well as several martyrs. In the East it was common to partition relics. In the West, however, there was more hesitance to touch, translate, much less partition the relics of saints. Only the holiest churchmen after fasting and prayer would do such a thing. Yet relics did spread and the Fifth Council of Carthage (401) required all altars to contain relics.[9]

Saints became more popular than the emperor and people eagerly wanted relics. St. Augustine, however, warned of merchants posing as monks selling fake relics. St. Gregory of Tours condemned the theft and sale of relics in Gaul. Such irreverence was so prevalent by the 400s that the Theodosian Code (438) forbade the translation, division, dismemberment, and the sale of relics. Pope Gregory the Great (590-604) continued this practice as far as possible, forbidding the unauthorized removal of relics of martyrs.[10]

For obvious reasons the authenticity of relics has always been important to the Church. Relics were authenticated early on and certifications can be traced to the 600s. These were very simple and crudely written in Latin. One such strip of parchment attached to a relic had this plain description in Latin: “Hic sunt patrocina sancti Petri et Paullo Roma civio.”[11]

The greatest relics are those connected with Our Lord. In 324 the emperor Constantine sent his mother Helena in search of the Holy Sepulchre and the Cross on which Our Lord died. She traveled to the Holy Land and with the help of Bishop Macarius of Jerusalem she succeeded in finding the Cross as well as its Title and the Nails from the Crucifixion. The bishop encased the upright beam of the Cross in silver and built a church over the place of crucifixion in 335, while other significant portions went to Constantinople and Rome. The Crown of Thorns also went to Constantinople. It is said that Constantine mounted one of the Nails in his helmet and made a bit for his horse out of another.[12]

Reliquaries were highly decorated to show the greatness of relics and to give more honor to them. They featured precious metals, gems, ivory, and enamels. They were large and small. There were relics of the Cross in reliquaries small enough to wear around the neck in the fourth-century just are there are reliquaries of that size today. Constantine also built one reliquary for the Apostles that was in fact an entire church.[13]

By the end of the 600s, relics were widespread even in newly converted countries. Gaul, now modern-day France, was filled with Catholic shrines as was England. Some merchants, perhaps better called relic thieves, supplied churches with relics. Deusdona is the best known among these. He was a deacon who organized caravans across the Alps in the spring and then made the rounds to monastic fairs. He acquired relics mainly from the catacombs of Rome and was the source for countless relic shrines in the Carolingian Empire. The Council of Mainz (813) attempted to prevent thefts by requiring permission for translations. but this didn’t stop Deusdona.[14]

Charlemagne, crowned Roman Emperor by the Pope in 800, promoted the veneration of relics throughout his realm. He wore a necklace with two crystal containers holding a piece of the Cross and hair from the Virgin Mary. The Imperial Chapel in Aachen held a vast collection including a dress of the Virgin Mary, Jesus’s swaddling clothes, a cloth used during John the Baptist’s beheading, and the waistcloth Jesus wore before his Crucifixion. Relics were a part of daily life. By this time, it was common to make oaths upon relics. Previously, the Frankish custom was to make them upon something such as a beard or a leader’s chair, but Charlemagne made it law that all oaths were either made in a church or upon a relic. One such formula reads as follows: “May God and the saint whose relics these are judge me.”[15]

Reliquaries holding sacred relics became more elaborate during the time after Charlemagne. The reliquary of St. Foy is one stunning example that survives from this period. Reliquaries dating from the eleventh century were also made in the shape of the body part of bone that it held. For instance, an arm shaped reliquary would actually have an arm in it.

The Crusades of the Middle Ages brought countless relics into Europe. According to one contemporary writer, Constantinople in the 1000s had “the remains some 476 saints represented by 3,600 individual relics.”[16] Relics of the Apostles, the Cross, the Shroud of Turin, the Blood of Christ, and even milk from the Virgin Mary came to Europe and England. No doubt there were false relics brought along with authentic ones just as there were in earlier centuries. King St. Louis IX acquired the Crown of Thorns and constructed a stunning reliquary in Paris for the Crown of Our Lord in the form of an entire chapel called San Chapelle.

The Three Wise Men relics at Cologne, Germany are housed in a huge 7’ long reliquary in the shape of Noah’s Ark – a very common design for larger reliquaries of the Middle Ages. Reliquaries, however, were not just simple storage containers. The Benedictine abbot and hagiographer, Thiofrid of Echternach (d. 1110), explains the importance of reliquaries by saying, “Who with fast faith touches the outside of the container whether in gold, silver, gems, or fabric, bronze, marble, or wood, he will be touched by that which is concealed inside.”[17]

The huge trade of relics occurring during the time of the Crusades led to more legislation. There were counterfeit relics and even false authentication documents. The Fourth Lateran Council of 1215 sought to end such abuse and ruled very clearly that relics could neither be sold nor displayed outside of a reliquary. This last point apparently encouraged the partition of bodies since they now had to be secured inside of a reliquary. The same council also addressed simony, which is the sin of buying or selling spiritual things. The name simony derives from the Bible which tells how the magician Simon Magus sought to buy spiritual powers from St. Peter. The Apostle rejected the offer telling him that such things cannot be bought. It is also simony to buy or sell first-class relics.[18]

The veneration of relics reached a high point during the years leading up to the Protestant Revolts of the 1500s. Pilgrimages abounded and shrines were the most visited places in Europe. Rome held the largest collection of relics in the world and tens of thousands of pilgrims went there each year to venerate them. Protestantism, however, with its support from powerful worldly monarchs forced changes upon European society that stamped out large segments of Christian society, including the veneration of saints. They destroyed countless shrines across Christendom. In response, King Philip II of Spain built San Lorenzo el Real in El Escorial to show his great reverence to the Church and relics. Today, one may still visit and see the thousands of relics on display there.[19]

Despite these events, the Catholic tradition of relics remained and strengthened. The Council of Trent, held in 1545-1563, acknowledged the principles regarding the veneration of relics as was previously held by the Church and established by tradition, but it also abolished abuses such as where relics were looked upon as a source of money. It was especially St. Charles Borromeo who was instrumental in implementing the reforms of the Council of Trent, and in 1577 he gave specific guidelines regarding reliquaries and the storage of relics. These became the basis of how relics would be preserved in the following centuries. For instance, he specified that reliquaries should be made of a quality wood or some precious material and covered with glass. He also required that some sort of authentication be attached. A full separate document as a certificate of authentication would become common during the 1600s and were quite standardized by the 1700s and remail largely unchanged today. This prominently displays the issuing authority’s coat of arms along with the name and ecclesiastic position, a description of the relic and reliquary, and is dated and signed with the proper seal that matches the red Spanish seal on the relic.[20]

The veneration of relics is an excellent example of the unity of Catholic tradition over the ages and into the present. Relics of saints from the last several hundred years receive the same veneration as saints from any other time during history. For instance, St. Philomena’s remains were discovered in 1802 and all we know is that she was a martyr, but she is a great intercessor and through her relics God has worked countless miracles. Catholics likewise venerate hair from St. Bernadette and St. Maximilian Kolbe. Both large and small reliquaries contain the remains of saints from various centuries, but the same honor is paid to them whether the fragment be an entire body or a minute particle encased in a tiny reliquary.[21]

The many revolutions that followed the French Revolution in 1789 saw the destruction of relics and reliquaries wherever it went. Even if the relic survived, the reliquary itself could be plundered for the precious metals and jewels that adorned it. Yet, the relic is the most important part and miracles continue to be worked through them today. The Catholic Church continues to require proof of miracles as part of the canonization process and these are scientifically scrutinized to be sure of the miraculous. One of the most amazing miracles which continues to occur is the liquification of the blood of St. Januarius at the Cathedral of Naples. This event usually occurs three times a year.

Relics today hold the same significance that they did in earlier eras. Every consecrated altar throughout the world is still is required by canon law to have at least one first-class relic. Relics are prominently displayed in churches throughout the world but also in private homes, although there are certain rules to be followed if you are the bearer of a relic. The 1984 Code of Canon law clearly forbids the selling of relics and outlines the proper use of relics. Yet, Deusdona has modern-day equivalents in eBay and other internet stores that are filled with relics for sale. Prior to the age of internet, private individuals would most likely have acquired relics from the Vatican, from religious institutions, or received them as family heirlooms passed from generation to generation. Yet, many today turn to the internet to buy and sell relics. Fake relics with fake documents are also offered for sale. People buy and sell relics as if they are common antiques. Granted, there are those who buy a relic to rescue it from profanation, therefore “ransoming” it to save it from desecration. Nonetheless, simony pervades this modern-day relic market.[22]

These holy remains are not the same thing as baseball cards or art collections. They are not something you collect for fun, or acquire because of beauty and pleasure. The purpose for keeping relics is still the same as it always was and they should be preserved and honored with a religious spirit. The bones of saints are those who are in heaven and their bodies will one day rise again from the dead. They should neither sit in a curio cabinet neglected nor on a bookshelf as ornaments because they bring us closer to God when they are properly venerated. This is why they are commonly held in magnificent shrines. Some shrines are like St. Anthony’s in Pittsburg with hundreds or even thousands of relics. Others like the shrine of the Forty Martyrs in Nagasaki, Japan have a handful of relics, while still others have entire bodies like at Nevers, France where St. Bernadette rests. If you have never made a pilgrimage to a shrine, perhaps consider doing so. If you have a relic in your home, ensure it is properly venerated. Purchase or make a suitable stand to display it where you commonly pray your daily prayers. Keep it in a place of honor because Catholic relics are not like other remains found in history; they continue to influence our world and inspire us towards the charity practiced by saints who are now in heaven.

_________________________

Bibliography

“Afterlife_of_Reliquary.Pdf.” Accessed August 7, 2021. https://www.ifa.nyu.edu/people/faculty/nagel_PDFs/Afterlife_of_Reliquary.pdf.

Catholic Answers. “Are There Any Rules Governing Relics?” Accessed August 6, 2021. https://www.catholic.com/qa/are-there-any-rules-governing-relics.

Bagnoli, et al, Martina. Treasures of Heaven. Cleveland Museum of Art, 2011. https://www.ifa.nyu.edu/people/faculty/nagel_PDFs/Afterlife_of_Reliquary.pdf.

Caridi, Cathy. “Canon Law and the Private Ownership of Relics (Part I).” Canon Law Made Easy, June 15, 2017. https://canonlawmadeeasy.com/2017/06/15/canon-law-and-private-ownership-of-relics/.

———. “Canon Law and the Private Ownership of Relics (Part II).” Canon Law Made Easy, May 17, 2018. https://canonlawmadeeasy.com/2018/05/17/canon-law-and-the-private-ownership-of-relics-part-ii/.

“Catalogue of the Syon Abbey Papers.” Accessed August 7, 2021. https://reed.dur.ac.uk/xtf/view?docId=ark/32150_s24q77fr332.xml.

Catholic University of America, ed. New Catholic Encyclopedia. 2nd ed. Detroit : Washington, D.C: Thomson/Gale ; Catholic University of America, 2003.

“Certificate of Authenticity of Relics,; 1651. – Colenda Digital Repository.” Accessed August 7, 2021. https://colenda.library.upenn.edu/catalog/81431-p3wd4q.

Church, Catholic, and Edward N. Peters. The 1917 Or Pio-Benedictine Code of Canon Law: In English Translation with Extensive Scholarly Apparatus. Ignatius Press, 2001.

“Church Law Not Clear-Cut on Offering Second-Class Relics for Donation.” Accessed August 6, 2021. https://catholicsentinel.org/Content/Social/Social/Article/Church-law-not-clear-cut-on-offering-second-class-relics-for-donation/-2/-2/24178.

CNA. “Https://Www.Catholicnewsagency.Com/News/34354/Sale-of-Saint-Relics-on-Ebay-Sparks-Catholic-Outcry.” Catholic News Agency. Accessed August 7, 2021. https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/news/34354/sale-of-saint-relics-on-ebay-sparks-catholic-outcry.

“Code of Canon Law – Book IV – Function of the Church (Cann. 1166-1190).” Accessed August 6, 2021. https://www.vatican.va/archive/cod-iuris-canonici/eng/documents/cic_lib4-cann1166-1190_en.html#PART_II.

“Code of Canon Law – Book IV – Function of the Church: Part III: Sacred Places and Times (Cann. 1205-1243).” Accessed August 6, 2021. https://www.vatican.va/archive/cod-iuris-canonici/eng/documents/cic_lib4-cann1205-1243_en.html#TITLE_I:

Coulombe, Charles A. A Catholic Quest for the Holy Grail. ST BENEDICT, 2017.

Courier, Catholic. “Authenticating and Protecting Relics | Catholic Courier.” Accessed August 6, 2021. https://catholiccourier.com/articles/authenticating-and-protecting-relics.

Craughwell, Thomas J. Saints Preserved: An Encyclopedia of Relics. Image Books, 2011.

———. St. Peter’s Bones: How the Relics of the First Pope Were Lost and Found … and Then Lost and Found Again. Image Books, 2014.

Cruz, Joan Carroll. Relics. Our Sunday Visitor, 1984.

———. The Incorruptibles: A Study of the Incorruption of the Bodies of Various Catholic Saints and Beati. Tan Books and Publishers, 1977.

Davies, S.J., Henry. Moral and Postorial Theology. 5th ed. Vol. II. Sheed and Ward, 1946.

Hawaii Catholic Herald. “Father Kenneth Doyle: How May I Obtain a First Class Relic?,” November 21, 2014. https://www.hawaiicatholicherald.com/2014/11/21/father-kenneth-doyle-how-may-i-obtain-a-first-class-relic/.

Foley, Henry. Records of the English Province of the Society of Jesus0: First Series. Burns and Oates, 1877.

Papal Encyclicals. “Fourth Lateran Council : 1215 Council Fathers,” November 11, 1215. https://www.papalencyclicals.net/councils/ecum12-2.htm.

Papal Encyclicals. “Fourth Lateran Council : 1215 Council Fathers,” November 11, 1215. https://www.papalencyclicals.net/councils/ecum12-2.htm.

Freeman, Charles. Holy Bones, Holy Dust: How Relics Shaped the History of Medieval Europe. Yale University Press, 2011.

Geary, Patrick J. Furta Sacra: Thefts of Relics in the Central Middle Ages – Revised Edition. Princeton University Press, 1990.

Hahn, Cynthia. “What Do Reliquaries Do for Relics?” Numen 57, no. 3/4 (2010): 284–316.

Hahn, Cynthia J., and Holger A. Klein, eds. Saints and Sacred Matter: The Cult of Relics in Byzantium and Beyond. Dumbarton Oaks Byzantine Symposia and Colloquia. Washington, D.C: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2015.

Harper, Elizabeth. “LA’s Patron Saint Is a Third-Century Martyr in a Postmodern Tomb.” Atlas Obscura, 09:00 400AD. http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/the-third-century-martyr-in-the-postmodern-tomb.

Herbermann, Charles G. The Catholic Encyclopedia Volume Twelve: Philip – Revalidation. Vol. 12. The Cahtolic Encyclopedia Press, INC, 1913.

The League of the Miraculous Infant Jesus of Prague. “History of the Infant Jesus of Prague.” Accessed August 4, 2021. https://infantprague.org/about-the-infant-jesus-of-prague/.

“ICHRusa – Internal Standards Document.” Accessed August 6, 2021. http://www.ichrusa.com/friends-of-saints/members/pdfs/ICHRusa%20relic%20standards.pdf.

“Instruction ‘Relics in the Church: Authenticity and Conservation’ (8 December 2017).” Accessed August 6, 2021. https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/csaints/documents/rc_con_csaints_doc_20171208_istruzione-reliquie_en.html.

Kerper, Rev. Michael. “Can I Buy a Relic?,” December 2015. https://www.catholicnh.org/assets/Documents/Worship/Our-Faith/Understanding/Relics.pdf.

Los Angeleno. “Los Angeles’ Little Known Patron Saint,” August 30, 2019. https://losangeleno.com/people/saint-vibiana/.

Malo, Roberta. “In the Graduate School of The Ohio State University,” n.d., 272.

Maria Stein Shrine. “Maria Stein Shrine.” Accessed August 6, 2021. https://mariasteinshrine.org/.

LAist. “Meet The Patron Saint Of LA You’ve Never Heard Of,” July 18, 2018. https://laist.com/news/entertainment/meet-the-patron-saint-of-los-angeles-youve-never-heard-of.

“Relics, Relics, Relics.” Accessed August 7, 2021. http://relicbadges.blogspot.com/2006/07/first-and-second-class.html.

“Relics.Pdf.” Accessed August 6, 2021. https://www.catholicnh.org/assets/Documents/Worship/Our-Faith/Understanding/Relics.pdf.

“Rubrics.” Accessed September 24, 2021. http://ichrusa.com/rubrics.html.

Shrines of Pittsburgh. “Saint Anthony Chapel.” Accessed August 7, 2021. https://pghshrines.org/about-st-anthony-chapel.

“Sanctorum Mater – Instruction for Conducting Diocesan or Eparchial Inquiries in the Causes of Saints.” Accessed August 6, 2021. https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/csaints/documents/rc_con_csaints_doc_20070517_sanctorum-mater_en.html#APPENDIX.

“SUMMA THEOLOGIAE: The Adoration of Christ (Tertia Pars, Q. 25).” Accessed August 6, 2021. https://www.newadvent.org/summa/4025.htm#article6.

“The Council of Trent – Session 25.” Accessed July 30, 2021. http://thecounciloftrent.com/ch25.htm.

NCR. “The Proper Use and Care of Saintly Relics.” Accessed August 6, 2021. https://www.ncregister.com/blog/the-proper-use-and-care-of-saintly-relics.

National Catholic Reporter. “Vatican Releases New Instruction on Authenticating, Protecting Relics,” 11:59am. https://www.ncronline.org/news/vatican/vatican-releases-new-instruction-authenticating-protecting-relics.

Voelker, Translator, Evelyn. “Charles Borromeo’s Instructiones.” Accessed August 7, 2021. http://evelynvoelker.com/.

Wall, J. Charles. Relics from the Crucifixion: Where They Went and How They Got There. Sophia Institute Press, 2016.

Aleteia — Catholic Spirituality, Lifestyle, World News, and Culture. “Why Are Saints’ Relics Placed inside Altars?,” January 29, 2020. https://aleteia.org/2020/01/29/why-are-saints-relics-placed-inside-altars/.

WINFIELD, NICOLE. “Vatican Issues New Rules on Saints’ Bones and Other Relics.” mcall.com. Accessed August 6, 2021. https://www.mcall.com/news/breaking/mc-nws-vatical-relics-rules-20171216-story.html.

Writer, Elizabeth Neff, Tribune Staff. “RELIGIOUS RELICS ARE TURNING UP ON INTERNET.” chicagotribune.com. Accessed August 6, 2021. https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-2000-08-06-0008060359-story.html.

________________________________

Footnotes

[1] “SUMMA THEOLOGIAE: The Adoration of Christ (Tertia Pars, Q. 25),” accessed August 6, 2021, https://www.newadvent.org/summa/4025.htm#article6.

[2] Charles G. Herbermann, The Catholic Encyclopedia Volume Twelve: Philip – Revalidation, vol. 12 (The Cahtolic Encyclopedia Press, INC, 1913), 734.

[3] Thomas J. Craughwell, St. Peter’s Bones: How the Relics of the First Pope Were Lost and Found … and Then Lost and Found Again (Image Books, 2014), xv.

[4] Patrick J. Geary, Furta Sacra: Thefts of Relics in the Central Middle Ages – Revised Edition (Princeton University Press, 1990), 296; Joan Carroll Cruz, Relics (Our Sunday Visitor, 1984), 1.

[5] Craughwell, St. Peter’s Bones, xiii.

[6] Craughwell, xiii, 38.

[7] Craughwell, 104.

[8] Craughwell, 45.

[9] Geary, Furta Sacra, 18.

[10] Geary, 57, 110–11; Charles Freeman, Holy Bones, Holy Dust: How Relics Shaped the History of Medieval Europe (Yale University Press, 2011), 33.

[11] Herbermann, The Catholic Encyclopedia Volume Twelve, 12:738.

[12] J. Charles Wall, Relics from the Crucifixion: Where They Went and How They Got There (Sophia Institute Press, 2016), 30, 31.

[13] Wall, 13.

[14] Geary, Furta Sacra, 44–45, 49, 82; Freeman, Holy Bones, Holy Dust, 77–78.

[15] Freeman, Holy Bones, Holy Dust, 69, 74; Geary, Furta Sacra, 38.

[16] Freeman, Holy Bones, Holy Dust, 125.

[17] Cynthia Hahn, “What Do Reliquaries Do for Relics?,” Numen 57, no. 3/4 (2010): 309.

[18] “Fourth Lateran Council : 1215 Council Fathers,” Papal Encyclicals (blog), November 11, 1215, Canon 62, https://www.papalencyclicals.net/councils/ecum12-2.htm.

[19] Freeman, Holy Bones, Holy Dust, 260–61.

[20] “Catalogue of the Syon Abbey Papers,” accessed August 7, 2021, https://reed.dur.ac.uk/xtf/view?docId=ark/32150_s24q77fr332.xml; “Saint Anthony Chapel,” Shrines of Pittsburgh, accessed August 7, 2021, https://pghshrines.org/about-st-anthony-chapel; Henry Foley, Records of the English Province of the Society of Jesus0: First Series (Burns and Oates, 1877), 563–64; “Certificate of Authenticity of Relics,; 1651. – Colenda Digital Repository,” accessed August 7, 2021, https://colenda.library.upenn.edu/catalog/81431-p3wd4q; Craughwell, St. Peter’s Bones, xvi.

[21] Craughwell, St. Peter’s Bones, 55–56; Charles A. Coulombe, A Catholic Quest for the Holy Grail (ST BENEDICT, 2017), 47, 49.

[22] “Instruction ‘Relics in the Church: Authenticity and Conservation’ (8 December 2017),” accessed August 6, 2021, https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/csaints/documents/rc_con_csaints_doc_20171208_istruzione-reliquie_en.html; “Sanctorum Mater – Instruction for Conducting Diocesan or Eparchial Inquiries in the Causes of Saints,” accessed August 6, 2021, https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/csaints/documents/rc_con_csaints_doc_20070517_sanctorum-mater_en.html#APPENDIX.