The following is an excerpt (Chapter V, pages 37-43) from Ancient and Medieval History (1946) by Francis S. Betten, S.J. Although some information may be outdated, the Catholic historical perspective it provides remains pertinent. Use the link at the bottom of post to read the previous/following pages. Use Search to find specific topics or browse using the Resources tab above.

CHAPTER V

THE TIGRIS-EUPHRATES LAND

THE LAND AND ITS INHABITANTS

35. The Country. — About a thousand miles to the northeast of the Nile we find the twin rivers Euphrates and Tigris, which, coming from the mountains of Armenia, run for the most part of their course parallel to each other. In our own times their beds join shortly before reaching the Persian Gulf. These rivers, like the Nile, were the makers of a country. Their entire lower valley had been formed from the mud and other deposits which they carried down from the highlands. The common valley they had formed was not so closely hemmed in as was that of the Nile. Towards the southwest no hills or bluffs separated it from the Arabian desert which in the north gave way to the mountains, valleys, and little plains of Syria, the seat of an active population, and the connecting link between Egypt and the Euphrates-Tigris region.

Like the Nile the two rivers which had made the rich bottom of this valley also kept it in good fertility by their annual overflow. But dikes, canals, and other artificial aids were more needed here than on the banks of the Nile. As long as civilized nations ruled the valley, care was taken of these engineering works.

The whole country, which in size about equals France, is divided into three districts. The southeastern part is called Chaldea, or Babylonia. North of it came Assyria, chiefly east of the upper Tigris. The wider section between the two rivers is called Mesopotamia, a Greek word, meaning “Between Rivers,” which name in modern times is occasionally applied to the entire Euphrates country. Mesopotamia was the least fertile, on account of its (slight) elevation above the level of the rivers, and it has never been the seat of any mighty state.

36. The Inhabitants. — Long before the beginning of written history, about 5000 B.C., this rich country was inhabited by a people called Sumerians, now believed to have been Hamites. They were remarkable for their high degree of civilization. Their flourishing land was invaded by Semites from the west, and through the intermingling of these two peoples arose a new population with new names — the Chaldeans (Babylonians) in the south and the Assyrians in the north. The Chaldeans were quick-witted, industrious, and fond of arts and literature; the Assyrians cared chiefly for conquests and for the gains of commerce. The arts and crafts and institutions of civilized life that existed in the valley had their origin in this early Sumerian culture, though they were greatly developed by the efforts of later generations. These admirable achievements we shall now study in detail.

GOVERNMENT AND PEOPLE

37. Classes of Society. — As in Egypt, republican institutions were unknown. The kings ruled with absolute power. They surrounded themselves with everything that could awe and charm the masses. Extraordinary magnificence and splendor removed them from the people. They gave audience seated on golden thrones. All who came into their presence prostrated themselves on the floor until bidden to rise.

The priests formed a highly privileged class. They not only performed the sacred ministrations in the temples, but like the Egyptian priests, they were also professional scholars, and in possession of all the various sciences that existed (§ 12). The royal officials of all ranks were preferably taken from their number.

There was not much of aristocracy. The two great classes of the people, separated by a large number of intermediary steps, were the rich and the poor, and below the poor a mass of slaves.

The peasants, like those of Egypt, paid for their holdings with a large part of the produce. In a poor year, this left them in debt for seed and living. The creditor could charge exorbitant interest; and, if not paid, he could levy not only upon the debtor’s small goods, but also upon wife or child, or upon the person of the farmer himself, for slavery. As early as the time of Hammurabi (§ 47), however, the law ordered that such slavery should last only three years.

The wealthy class included landowners, officials, professional men, money lenders, and merchants. The merchant in particular was a prominent figure. The position of Chaldea, at the head of the Persian Gulf, made its cities the natural mart of exchange between India and Syria; and for centuries, Babylon was the great commercial center of the ancient world, far more truly than London has been of our modern world. Even the extensive wars of Assyria, cruel as they were, were not merely for love of conquest: they were largely commercial in purpose — to secure the trade of Syria and Phoenicia, and to ruin or cripple in those lands the trade centers that were competing with Nineveh, as Damascus, Jerusalem, and Tyre.

38. Babylonian Laws. — In the ruins of this remarkable country there have been discovered all kinds of legal documents, wills, deeds, marriage settlements, contracts, by tens of thousands, written carefully on baked clay tablets, each signed by the contracting parties and by witnesses. Large numbers of people, therefore, must have been able to read and write, and more than this, such documents suppose an orderly government and well-knit systems of public laws. From these contracts we learn, among other things, that the business relations existing among the people were of similar character and almost as manifold as in our own days. We find for instance that a woman could hold property in her own name and carry on business independently of her husband.

The crown of all these laws is the Code of Hammurabi (§ 47), which was discovered in 1902 by a French explorer. A great deal of the regulations it contains existed before Hammurabi’s time, but he reproduced them in a more systematic manner, and supplemented them with enactments of his own. The code tries to guard against bribery of judges, against careless medical practices, against ignorant or dishonest building contractors, and against fraudulent proceedings of business men and their agents. Thus it implicitly also testifies to the existence of a very high degree of civilization at the time when it was introduced.

Many of its ordinations, however, cannot receive our approval, least of all the difference it makes between the great and the lowly. Here it reminds us of the Jewish law of “an eye for an eye” and “a tooth for a tooth.” It says: “If a man has caused a man of rank to lose an eye, one of his own eyes must be struck out. If he has shattered the limb of a man of rank, let his own limb be broken. If he has knocked out

INDUSTRIES AND ARTS

the tooth of a man of rank, his tooth must be knocked out.” It is different if a poor man is injured. “If he has caused a poor man to lose an eye, or has shattered a limb, let him pay a manch of silver” (about $32).

INDUSTRY AND LEARNING

39. Industries and Arts. — More than the other ancient peoples, the men of the Euphrates made practical use of their science. They understood the lever and pulley, and used the arch in making vaulted drains and aqueducts. In the earliest times they employed the potter’s wheel and devised an excellent system of weights and measures. Their measures were based on the length of the finger, breadth of the hand, and length of the arm; and, with the system of weights, they have come down to us through the Greeks. Books upon agriculture passed the Babylonian knowledge of that subject on to the Greeks and Arabs. In the cutting of gems, and enameling, in the production of fine linens and fleecy woolens and artistic embroidery, no nation has ever done better than they.

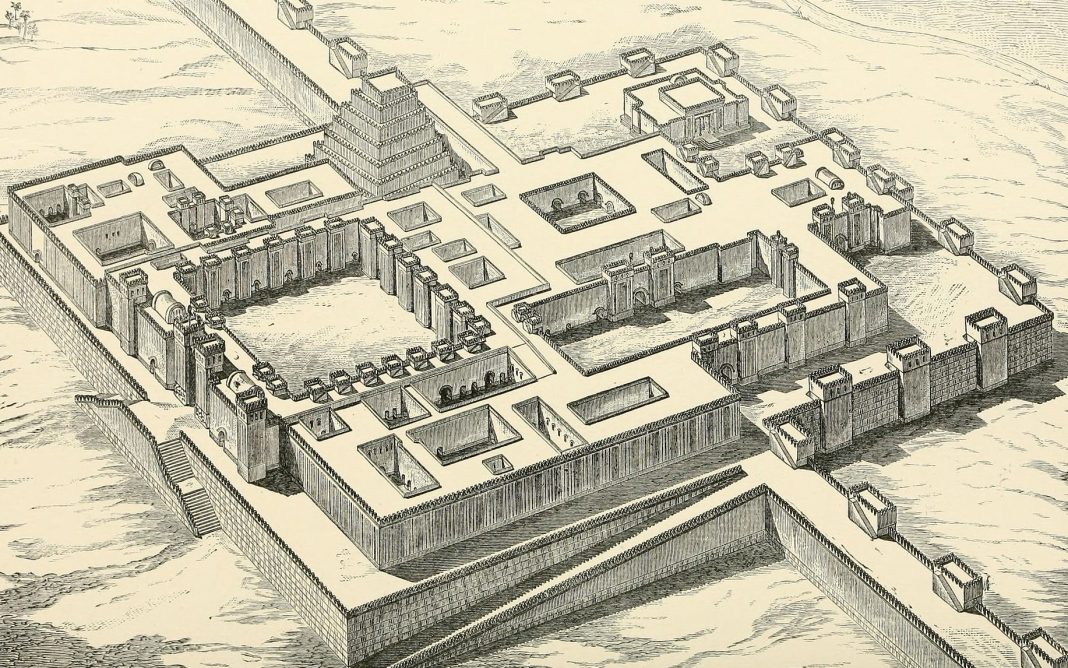

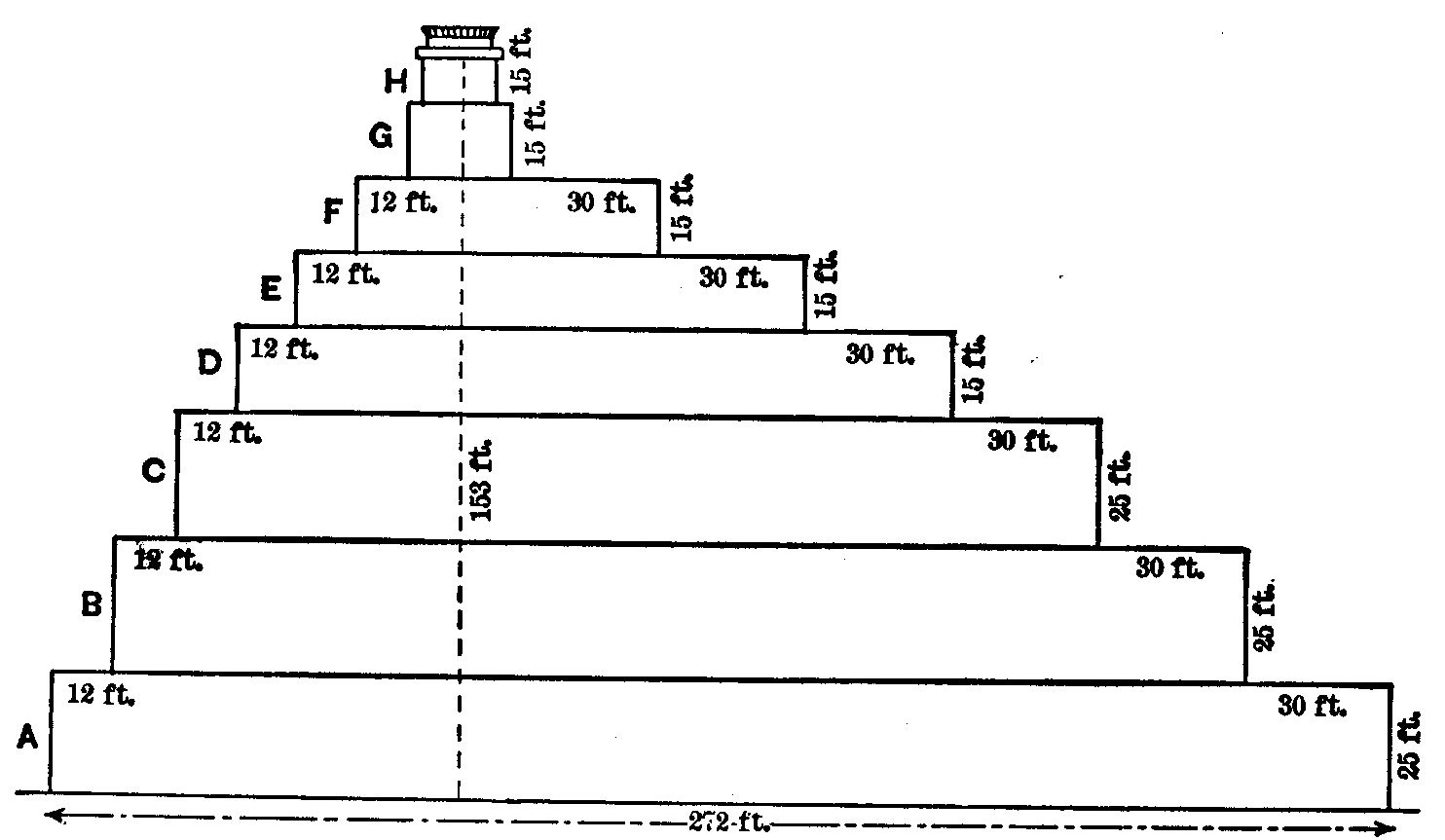

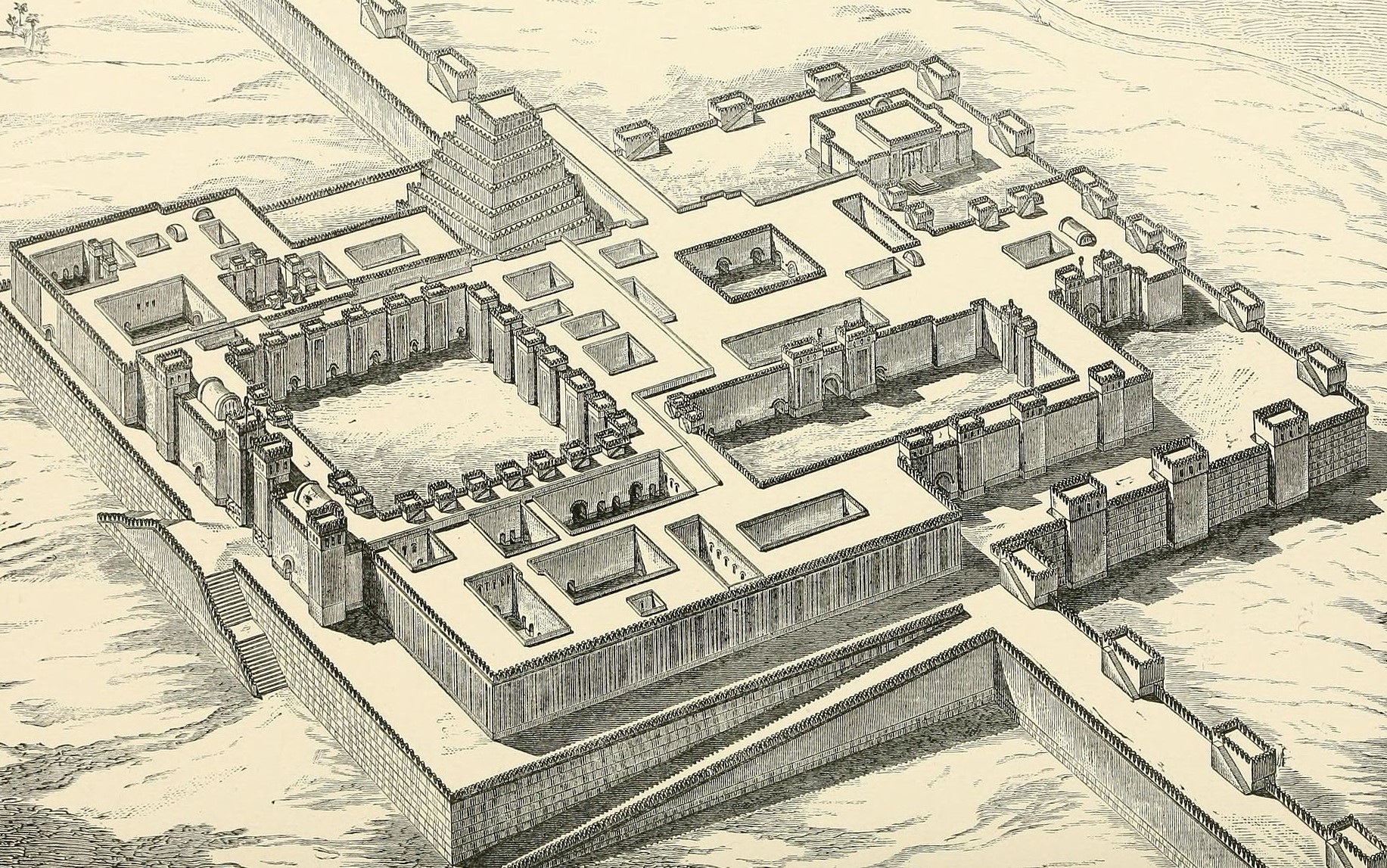

40. Architecture and Sculpture. — The Euphrates valley had no stone and little wood. Brickmaking, therefore, was, next to agriculture, the most important industry. Ordinary houses were built of cheap sun-dried bricks. In other words, the walls were simply clay walls. To be firm they had to be very thick. To be durable they must be protected from rain by careful roofing. Although the Babylonians possessed an admirable skill in making kiln-baked brick, they used the sun-dried material most extensively, even in their gigantic public buildings. Commonly the walls were only given a strong facing of kiln-dried bricks. This is the reason why their massive structures are in so deplorable a state of decay. But their works, temples as well as palaces, were marvelous, both in size and magnificence.

Statues, so common in Egypt, are almost unknown among the ruins of the Euphrates-Tigris lands. Sculpture, generally speaking, was restricted to reliefs, carried out in large numbers and all sizes on the walls, even brick walls, and on the rocks in the mountains, and always in connection with inscriptions.

A palace of Nineveh is thus described by a modern scholar. “Upon a huge artificial hill, faced with masonry, for a platform, rose cliff-like fortress walls a hundred feet more. Sculptured portals, by which stood as silent guardians colossal figures in white alabaster, the forms of men and beasts, winged and of majestic mien, admitted to the magnificence within. Upward, tier above tier ran lines of colonnades, pillars of costly cedar wood, blazing with gold and vermilion, and between them voluminous curtains of silk, purple, and scarlet, woven with threads of gold.”

41. Science. — In geometry the Chaldeans made as much advance as the Egyptians; in arithmetic more. Their notation combined the decimal and duodecimal systems. Sixty was a favorite unit, because it is divisible by both ten and twelve: it was used as the hundred is by us.

Scientific medicine was hindered by a belief in charms and magic; and even astronomy was studied largely as a means of fortune-telling by the stars. Some of our boyish forms for “counting out” — “eeny, meeny, miny, moe,” etc. — are remarkably like the solemn forms of divination used by Chaldean magicians. (This sort of fortune-telling is called “astrology” to distinguish it from real astronomy.) Still, in spite of such superstition, important progress was made. The Chaldeans foretold eclipses, made star maps, and marked out on the heavens the apparent yearly path of the sun. The “signs of the zodiac” in our almanacs come from these early astronomers. In 331 B.C., Alexander the Great found an unbroken series of observations running back nineteen hundred years. As we get from the Egyptians our year and months, so through the Chaldeans we get the week, with its “seventh day of rest for the soul,” and the division of the day into hours, with the subdivision into minutes. Their notation, by 12 and 60, we still keep on the face of every clock. Though it is not sure that the Chaldeans invented the sundial and the water clock, they were certainly acquainted with these devices at a very early date.