The following is an excerpt (pages 369-379) from Ancient and Medieval History (1944) by Francis S. Betten, S.J. Although some information may be outdated, the Catholic historical perspective it provides remains pertinent. Use the link at the bottom of post to read the previous/following pages. Use the Search box above to find specific topics or browse using the Resources tab above.

CHAPTER XXXIV

LIFE IN THE FEUDAL AGE

There were few towns in western Europe until the twelfth century, and the new town life of that period will be discussed in its place (§§ 604 ff.). Society was mainly rural. It is the work and the home life of this rural society with which this chapter deals. The essential features of medieval life were more or less the same all over feudal Europe. But we have here in view chiefly the conditions and customs of England.

From a thirteenth-century manuscript.

LIFE OF THE WORKERS

480. The Manor. — The possessions which the knight cultivated through his own villeins (or serfs) formed a manor, the center of which was his castle, grand or modest, according to his means. Rich landowners, however, divided their estates into several manors often widely separated. In each manor they erected a manor house, in which the chief steward lived and the crops and provisions were stored. Some manor houses were only more spacious and a little better than the dwellings of the villeins; others were imposing and more similar to the castle proper. The serfs and villeins commonly lived together in a village near the manor house. Each village had its church, usually at a little distance, with grounds about it, part of which was used as a graveyard, “God’s Acre.” At one end of the village street was the lord’s smithy, and on some convenient stream the lord’s mill. The smith and the miller were usually serfs or villeins, and spent most of their labor on the land, but they were somewhat better housed and more favored than the rest of their class.

This shows its present condition. The stairway leading to the upper story is cut into the thick wall. (From Wright’s Homes of Other Days.)

Peasant Homes.—The other dwellings were low and narrow, plainly built of wood and clay, and thatched with straw. They had usually no chimney or floor, and often no opening (no window) except the door. They straggled along either side of an irregular lane. Behind each house was its garden patch and its low stable and barn.

481. Farming. — The plow land was divided into three great “fields” or rather groups of fields. One group was sown to wheat (in the fall); one to rye or barley (in the spring); and the third lay fallow, to recuperate. The next year this third field would be the wheat land, while the old wheat field would raise the barley, and so on. This primitive “rotation of crops” kept a third of the land idle.

Every field was divided into a great number of narrow strips, each as nearly as possible a “furrow-long,” (this expression is the origin of our “furlong,” about 220 yards) and one, two, or four rods wide, so that each contained from a quarter of an acre to an acre. A peasant’s holding was about thirty acres, ten acres in each field; and his share in each lay not in one piece, but in fifteen or thirty scattered strips. The lord’s land, probably half the whole, lay in strips like the rest. This kind of holding compelled a “common” cultivation.

Each man must sow what his neighbor sowed; and as a rule, each could sow, till, and harvest only when his neighbors did. Agriculture was crude. Walter of Henley, a thirteenth-century writer on agriculture, says that threefold the seed was an average harvest, and that often a man was lucky to get back his seed grain and as much again.

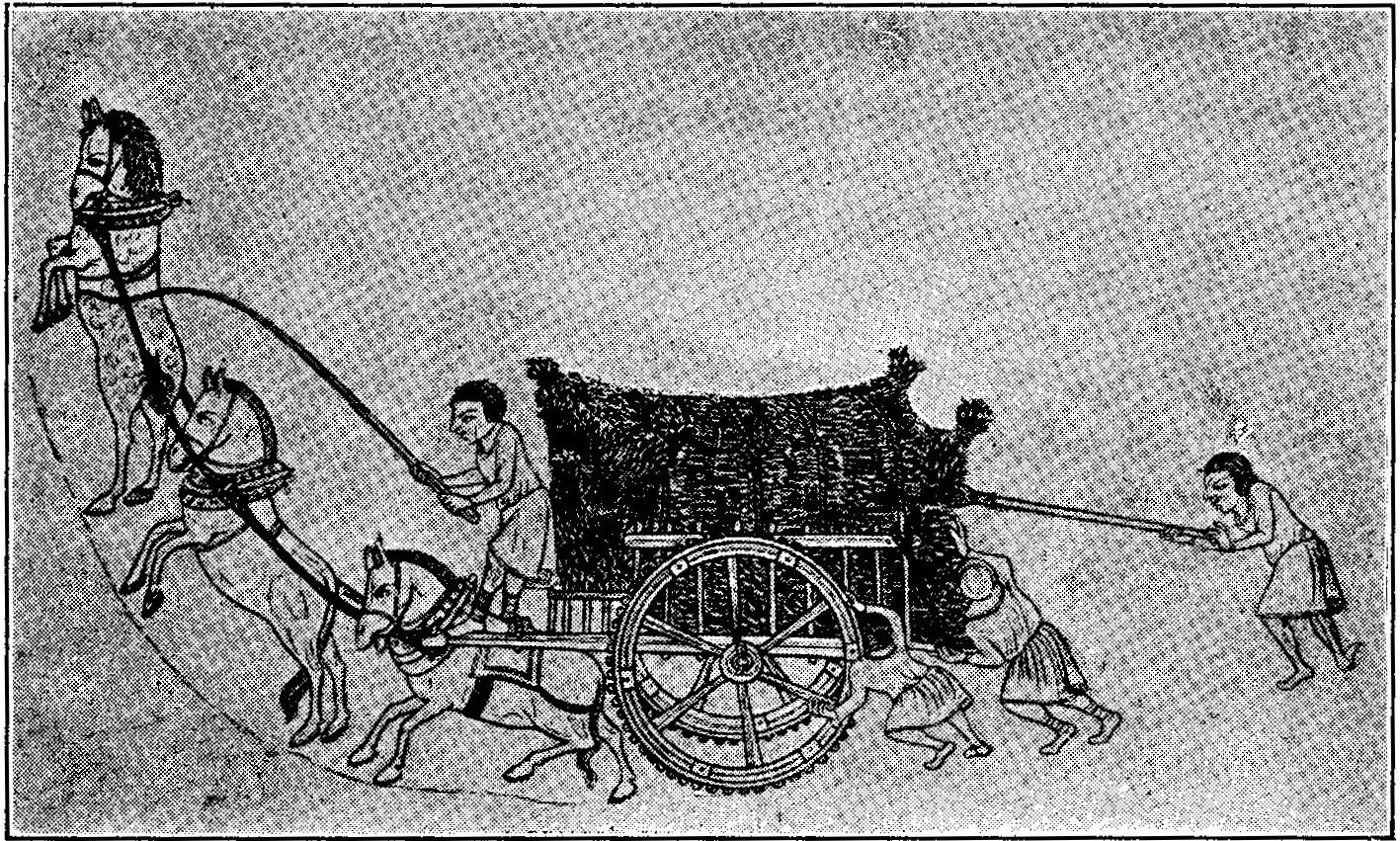

The plow, made almost entirely of wood, required eight oxen, and then it did hardly more than scratch the surface of the ground. (See the picture on page 372.) Carts were few and cumbrous. The distance to the outlying parts of the fields added to the labor of the villagers. There was little or no cultivation of root foods. Potatoes, of course, were unknown. Sometimes turnips and cabbages and carrots were grown in garden plots behind the houses. The wheat and rye in the fields were raised for breadstuffs, and the barley for brewing beer. The most important crop was the wild hay, upon which the cattle had to be fed during the winter. Meadowland was twice as valuable as plow land. The meadow was fenced for the hay harvest, but was afterward thrown open for pasture. Usually there were other extensive pasture and wood lands, where lord and villagers fattened their cattle and swine. It was difficult enough to carry animals through the winter for the necessary farm work. So those to be used for food were killed in the fall and salted down. The large use of salt meat and the little variety in food often caused diseases among the people. The chief luxury among the poor was honey, which took the place of sugar.

After Jusserand’s English Wayfaring Life: from a fourteenth-century manuscript. The force of men and horses indicates the nature of the road. The steepness of the hill is, of course, exaggerated so as to fit the picture to the space in the manuscript.

482. Each village was a world in itself. Even the different villages of the same lord had little intercourse with one another. Each produced everything it needed. The lord’s bailiff secured from some distant market such products as could not be supplied at home, e.g., salt, millstones, and iron. Except for this, a village was hardly touched by the great outside world. This shut-in life was monotonous. Yet pictures found in the manuscript books of the time show that it was by no means without its pastimes and amusements. We shall see how wholesome an influence was exercised on it by the Church (§§ 491, 496).

From an Anglo-Saxon manuscript in the British Museum.

483. The Court of the Manor. — The manor was self-sufficient to a large extent even in the line of government. At its head was the court of the manor, composed of all the men. This court met every three or four weeks. As all the holdings in the manor were hereditary, customs had grown up which it was beyond the steward’s and even the lord’s power to change. The court decided cases according to this unwritten law. The lord’s steward presided and exercised very great power; but all the villagers took part, and the older men had an important voice in declaring “the custom of the manor,” a thing which differed in every two manors, and which held the place of town legislation among us.

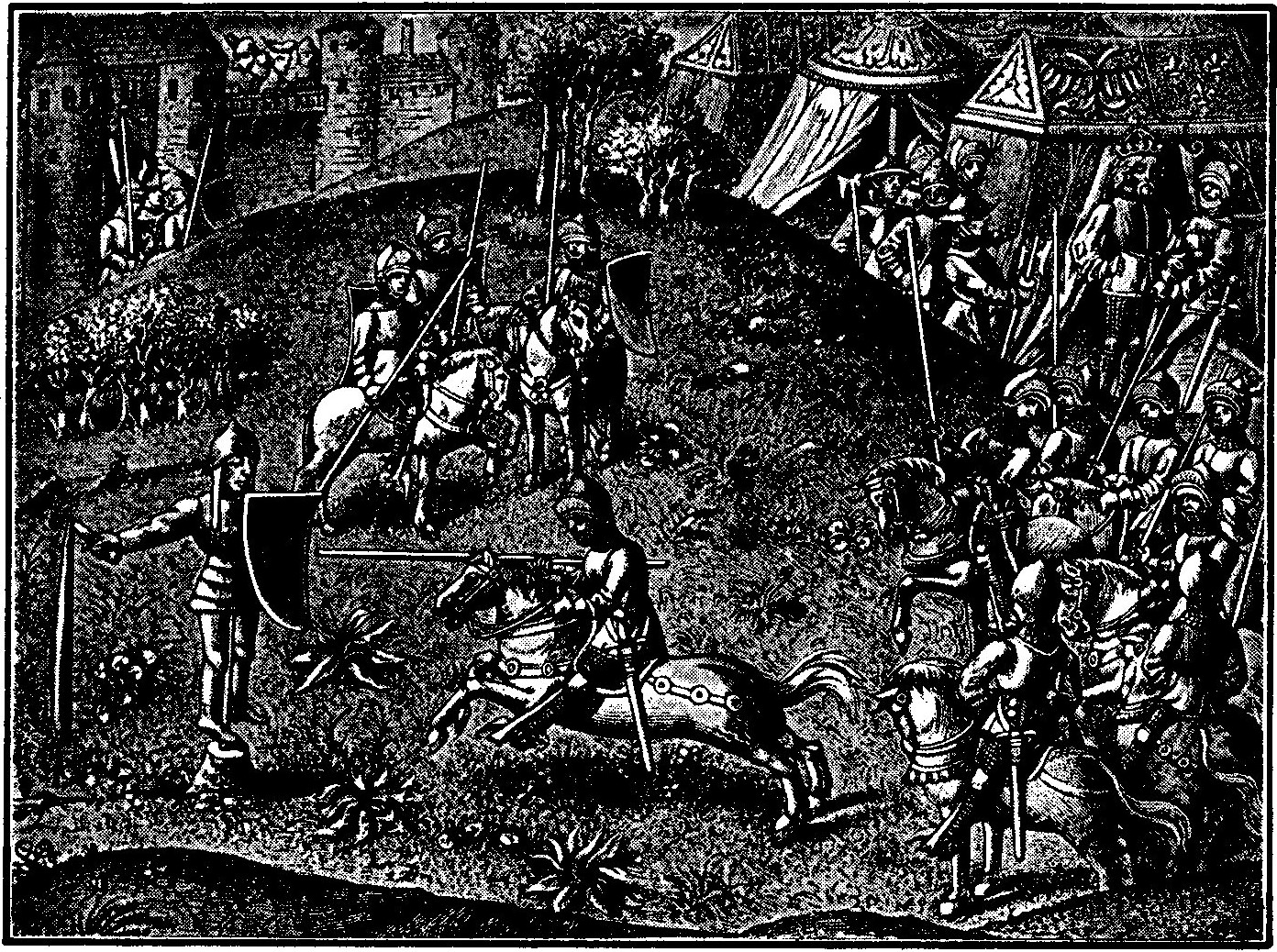

From a miniature in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris.

The assembly settled disputes between villagers, imposed penalties upon any who had broken “the customs of the manor,” and, from time to time, redistributed the strips of plow land among the village families. In England such gatherings sent their presiding officer and their “four best men” to the larger local assemblies.

LIFE OF THE NOBLES

484. Life in the Castle. — When not actually engaged in war or in some private feud, the nobleman lived in his castle and enjoyed the company of his family. He trained his sons or pages in the military arts and showed interest in their progress. He looked after the administration of his estates. The courts

(§ 470, 2) also took up much of his time.

The lady was the queen of the castle and herself supervised all the details of the household. The bunch of keys which hung from her belt was the exterior sign of her dominion. But she was well acquainted with the finer arts of embroidery as well, and took pride in displaying the work of her nimble hands. The famous Bayeux Tapestry (see pictures in § 504) is said to have been made by Mathilda, the wife of William the Conqueror; this is rather doubtful, but the fact that it is attributed to her shows what occupations and accomplishments were considered both honorable and desirable in ladies of rank.

After a drawing by Dürer.

485. The favorite sport of this fighting age was a sort of mock battle called a tournament. Kings and great lords gave such entertainments, to win popular applause, on all joyous occasions, — the marriage of a daughter, the knighting of a son, the celebration of a victory.

Every student should know the splendid story of the combats in “the lists of Ashby” in Scott’s Ivanhoe, and any mere description is tame in comparison. As there portrayed, the news of the coming event was carried far and near for weeks in advance. Knights began to journey to the appointed place, perhaps from all parts of a kingdom, in groups that grew ever larger as the roads converged. Some came to win fame; some to repair their fortunes, — since the knight who overthrew an opponent possessed his horse and armor and the ransom of his person, as in real war. The knightly cavalcade might be joined or followed by a motley throng journeying to the same destination; among them, jugglers to win small coins by amusing the crowds, and traveling merchants with their wares on the backs of donkeys.

The contests took place in a space (the “lists”) shut off from interference by palisades. The balconies above, gay with streamers and floating scarfs, were crowded with ladies and nobles and perhaps with rich townsmen. Below, a mass of peasants and other common men jostled one another for the better chances to see the contestants. Sometimes two or more days were given to the combats. Part of the time, one group of knights “held the lists” against all comers, affording a series of single combats on horseback and on foot.

486. Chase and Falconry. — Hunting was the second most important sport of the nobles, and it was a monopoly possessed by that class, protected by cruel and bloody custom. Indeed, it was more than sport. The table of every castle depended in large measure upon a steady supply of game. The larger wild animals, —- bear, deer, wild boars, — were brought to bay with dogs, and slain by the hunter with spear or short sword. (This was the “chase.”) Smaller game, — herons, wild ducks, rabbits, — were hunted with trained hawks. (This was “falconry.”) Each castle counted among its most trusted servants a falconer, who saw to the capture of young hawks (falcons) and trained them to fly at game and to bring it back to the master. Many a noble lady, even on a long journey of many days, rode, falcon on wrist, ready at any moment to “cast off” if a game bird rose beside the road.

487. Feasting filled a large part of the noble’s life. Meals were served in the great hall of the castle, and were the social hours of the day. Tables were set out on movable trestles, and the household and visitors gathered about them on seats and benches, — the master and his noblest guests at the head. A profusion of food in many courses was carried in from the kitchen across the open courtyard. Peacocks, swans, whole boars, or at least boars’ heads, were among the favorite roasts; and huge venison “pies” were a common dish.

At each guest’s place was a knife, to cut slices from the roasts within his reach, and a spoon for broths, but no fork or napkin or plate. Each one dipped his hand into the pasties, carrying the dripping food directly to his mouth. Loaves of bread were crumbled up and rolled between the hands to wipe off the surplus gravy, and then thrown to the dogs under the tables; and between courses, servants passed basins of water and towels. The food was washed down with huge drafts of wine, usually diluted with water. A prudent steward of King Louis IX of France tells us how he “caused the wine of the varlets (at the bottom of the tables) to be well watered, but less water to be put in the wine of the squires, and before each knight [he] caused to be placed a huge goblet of wine and a goblet of water,” — a judicious hint which it is to be hoped some knights accepted.

During the midday and evening meals, there was much opportunity for conversation, especially with strange guests, who repaid the hospitality by the news of the districts from which they came. Intervals between courses, too, were sometimes filled with story-telling and song, and with jokes by the lord’s “jester” or “fool.”

After a medieval miniature in brilliant colors. Many great lords kept such Jesters.

488. Chivalry. — This grim life had its romantic and gentle side, indicated to us by the name chivalry. The term at first meant the nobles on horseback (from the French cheval, horse), but it came to stand for the whole institution of “knighthood.” Chivalry grew up slowly between 1000 and 1200 a.d. We will look at it in its fully developed form.

There were two stages in the training of a young noble for knighthood.

(1) At about the age of seven he was sent from his own home into the household of his father’s suzerain, or of some other noble friend, to become a page. Here, for seven or eight years, with other boys, he waited on the lord and lady of the castle, serving them at table and running their errands. As soon as he was strong enough, he was trained daily, by some old man-at-arms, in riding and in the use of light arms. But his attendance was paid chiefly to some lady of the castle, and by her, in return, he was taught obedience, courtesy, and a knight’s duty to religion and to ladies,

(2) At fourteen or fifteen the page became a squire to the lord. He oversaw the care of his lord’s horse and the cleaning of his shining armor; he went with his lord to the hunt, armed him for battle, carried his shield, and accompanied him in the field, with special care for his safety.

The boys ride, by turns, at the wooden figure. If the rider strikes the shield squarely in the center, it is well. If he hits only a glancing blow, the wooden figure swings on its foot and whacks him with its club as he passes.

After five or six years of such service, at the age of twenty or twenty-one the squire’s education was completed. He was now ready to become a knight. Admission to the order of knighthood was a matter of imposing ceremonial. The youth bathed (a symbol of purification), fasted, made his confession to a priest, and then spent the night in the chapel in prayer, “watching” his arms. In the morning there followed solemn religious services with a sermon treating of knightly duties. Then the household and vassals gathered in the castle yard, along with many visiting knights and ladies. In the background of this gay scene a servant held a noble horse, soon to be the charger of the new knight. The candidate knelt before the lord of the castle, and there took the “vow” to be a brave and gentle knight, to defend the Church, to protect ladies, to succor the distressed, especially widows and orphans. The lord of the castle or some other prominent knight struck him lightly over the shoulder with the flat of the sword, exclaiming, “In the name of God, of St. Michael, and of St. George, I dub you knight.” This was the “accolade.” Next the ladies of the castle put his new armor upon him, gave him his sword, and buckled on a knight’s golden spurs. When thus accoutered the newly made knight vaulted upon his horse and gave some exhibition of his skill in arms and in horsemanship; and the festival closed with games and feasting and the exchange of gifts.

More honored still was the noble who had been dubbed knight by some famous leader on the field of victory, as the reward for distinguished bravery. In such case, there was no ceremony except the accolade.

489. The Christian character of knighthood is clearly shown in the ceremonies of the solemn knighting and the oath taken by the young nobleman. There were never wanting men who carried out their obligations most conscientiously. Thus chivalry exercised a salutary effect upon the views of the higher classes. It put a high ideal, founded on both reason and faith, before the eye of the knight. Gallantry, as long as it was based upon the veneration of the Lady of Ladies, the Virgin Mother of God, could not fail to produce nobleness of sentiment, purity of morals, and elegance of manner. The knight’s example was certainly wholesome for the lower classes. When, in later times, wealth and with it the level of life rose among all classes, the cultured manners of chivalry were eagerly copied, to the great benefit of society.

490. Drawbacks. — Not every knight’s breast harbored these lofty sentiments. Hideous crimes disfigured the record of many a “noble” warrior who had performed great deeds of valor. The lawless “robber knight” who made his living by preying upon the fortune of defenseless wayfarers was, however, chiefly the product of later centuries with completely altered social and economic conditions. The respect for women often degenerated into knight-errantry, an exaggerated and ridiculous cult of the female sex, of which the Spaniard Cervantes, in his famous Don Quixote, gives an amusing caricature. The whole system, too, by conferring great privileges upon the nobility, was apt to lead to a contempt of the lower classes. Yet all this should not lead us to a wholesale condemnation of a system which was, at any rate, the best those times could devise, and which in itself was calculated to emphasize the practice of eminently Christian virtues.