The following is an excerpt (pages 517-526) from Ancient and Medieval History (1944) by Francis S. Betten, S.J. Although some information may be outdated, the Catholic historical perspective it provides remains pertinent. Use the link at the bottom of post to read the previous/following pages. Use the Search box above to find specific topics or browse using the Resources tab above.

CHAPTER XLIV

THE GERMAN LANDS AFTER THE CRUSADES

EMPIRE AND EMPERORS

649. The Interregnum, 1255-1273. — Toward the end of the Hohenstaufen period seven of the German princes had arrogated to themselves the exclusive right of choosing the King of the Romans. After the death of Conrad IV (§567) these seven “electors” could not unite on one candidate. One faction elected Richard of Cornwall, brother of Henry III of England (§ 529). Richard visited his kingdom three times without exerting much influence. The other faction decided for Alphonso of Castile, who never saw Germany. The period 1254-1273, during which these two foreigners were supposed to rule, while in reality nobody ruled, is called interregnum (time between reigns). It was the heyday of club-law, when robber knights in ever-increasing number infested the country. To combat the evils of the period the city leagues grew into power (§ 612) and, as far as their influence reached, safeguarded the roads for traveling merchants.

650. Rudolph of Hapsburg (1273-1291) was a man of sterling character, and likely to bring some order out of the chaos. His moderate possessions, southern Alsace and some territory in the Alps, made him acceptable to the great princes who did not want too powerful a king. His election was hailed with unbounded joy by the people. Rudolph was sincerely religious. From the first he had the active support of the popes. He showed little inclination to interfere in Italian affairs, but gave his undivided energy to the welfare of Germany itself. The robbers soon found out what kind of man the new king was. Along the Rhine alone he demolished a hundred and fifty of their castles, and on one memorable occasion hanged twenty robber knights at a single execution.

Rudolph was forced to draw the sword also for the integrity of the realm. King Ottokar of Bohemia (§ 454) had brought that country to a high degree of prosperity. But he sought to withdraw his possessions from the overlordship of the Empire and refused to give up other fiefs which he had occupied with very questionable right. With greatly inferior numbers Rudolph defeated him. Ottokar fell in the battle. Rudolph bestowed Bohemia and Moravia upon Ottokar’s infant son. Most of the other fiefs, among them the dukedom of Austria (founded as the East Mark by Otto I, § 551), he granted to his own son Albrecht. Thus the family of the Hapsburgs was established in the land on the Danube, which was destined to grow into the Austrian Monarchy under Rudolph’s descendants.

Rudolph’s rule proved an immense blessing for Germany. But his actual influence did not extend very far into the north. The short reigns of the contemporary popes — there were eight during his own reign — must be assigned as one of the reasons that prevented his imperial coronation.

651. For fifty years after Rudolph’s death the crown passed from one family to another. Henry VII, of the House of Luxemburg, again went to Rome and was crowned Emperor, only to die in Italy after a short while. His successor, King Louis, Duke of Bavaria, was for sixteen years at war with a rival, and lived in unending opposition to the popes, who then resided at Avignon (§ 666). He led an immoral life and broke the most solemn pledges. His reign is remarkable only because of the favor he bestowed upon the free cities.

Here is the place to sum up the chief causes of the decline of Germany. They are: the disastrous Italian policy of many of the emperors; the complete electiveness of the royal office; the large number of short reigns; and the continuous change of the ruling houses. (§ 556, note.) To these causes will be added in the coming centuries the aggressiveness of strong foreign powers, chiefly France and the Turks, and the internal disunion fostered enormously by the Reformation.

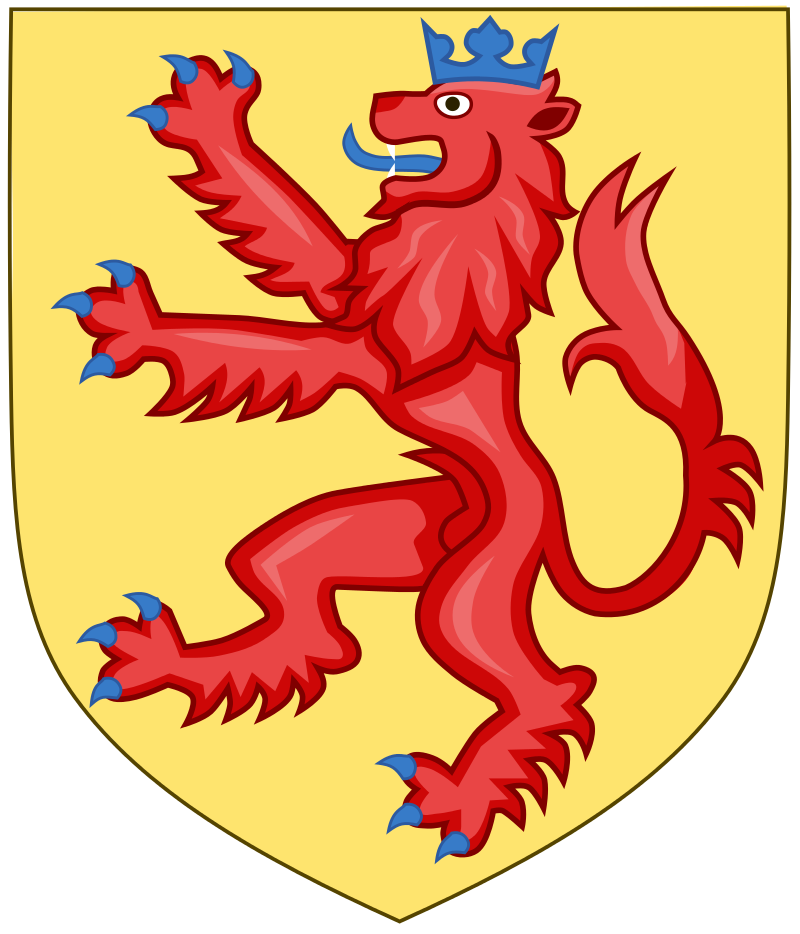

652. Charles IV (1347—1378), grandson of Henry VII, was a good emperor. He had received his education in Paris, spoke Bohemian, German, French, and Latin, and was a great promoter of learning and art. In his residence, Prague, he established a university, the first in Germany, which was soon frequented by thousands of students. With the power of his rich private dominions he might have consolidated Germany or at least greatly retarded its disintegration. The cities and the lower nobility would have been his mighty allies. But his was too conservative a nature. On the whole, however, his rule was a happy one. He formally sanctioned the privileges of the seven electors. His Golden Bull defined exactly how the “ College of Electors ” should make elections, and fixed its members as the three archbishops of Mainz, Cologne, and Treves, the King of Bohemia, the Duke of Saxony, the Margrave of Brandenburg (§ 550), and the Count Palatine by the Rhine. Thus he forestalled arbitrariness in the royal elections at least to some degree.

The apple of his eye was his own kingdom of Bohemia. “Under the long reign of this wise and learned king,” says a Bohemian writer, “the Bohemians themselves became wise and learned. The surrounding nations now sent their sons to the new university. Bohemians obtained the most important positions in the Empire. Several foreign bishoprics received Bohemian bishops. The Bohemians were the most learned, the dominant nation in Europe. It was thought a great honor to be a Bohemian. The neighboring princes bought or built houses in Prague to live among the Bohemians.”

Another, prominent ruler of the Luxemburg family was Sigis- mund (1410-1437) the son of Charles IV. In addition to his private possession of Bohemia he acquired by marriage the kingdom of Hungary. His greatest merit was the prominent part he played in the happy termination of the Great Western Schism (§ 673). This will be seen later. In the Empire he fulfilled the expectations entertained of him much less than Charles IV.

(See § 656.) From a fifteenth-century manuscript.

653. From 1437 onward all the emperors were elected from the House of Hapsburg, the descendants of Rudolph. The dignity did not, however, simply become hereditary. The election always remained a reality. More than once the imperial crown was on the point of slipping away and nearly every election resulted in a further limitation of the royal power. One more reign during the present period is important, that of Maximilian I (1493-1519). He found it impossible to go to Rome for his coronation, and the Pope permitted him to style himself Emperor Elect. The only German ruler that was crowned Emperor after him was Charles V. The others obtained the same privilege as Maximilian. The title of “Roman King” (§ 554) was now reserved to those few who were elected during an emperor’s lifetime to succeed him after his death.

Maximilian I, called “the last of the knights,” was one of the most romantic figures of the closing Middle Ages. Most of his noble efforts to bring Germany abreast of England and France were frustrated by the jealousies of the princes and partly by his own dreamy nature.

Until 1806 Germany was simply called “The Empire,” and its ruler “The Emperor,” because there was but one emperor in the Christian world. Historians, however, occasionally use the appellation of “German Empire” and “German Emperor” with reference to those centuries. There was no Emperor of Austria then. But the ruler of the dominions of the House of Hapsburg, to which belonged the Archdukedom of Austria, was the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation.

654. Institutions of the Empire. — The Diet. — During this period the German “national assembly,” called the Diet, took form. It consisted of three houses, the Electors, the Princes, and the Representatives of the “Free and Imperial Cities.” To be binding a resolution had to be passed by at least two houses and signed by the emperor. The execution of laws thus adopted was always difficult for the emperor.

The honest endeavors of Maximilian I had scored at least some success. Under him private feuds were completely forbidden, a Supreme Tribunal was instituted to settle disputes, and for the purpose of a better enforcement of the laws and of carrying out the verdicts of the tribunal, Germany was divided into ten “circles.” It took some time before both institutions were in working order and able to do a limited amount of good.

SWITZERLAND, BURGUNDY

We have to register two events in the history of the Hapsburg dominions, one a loss, small but significant, the other a great and important gain.

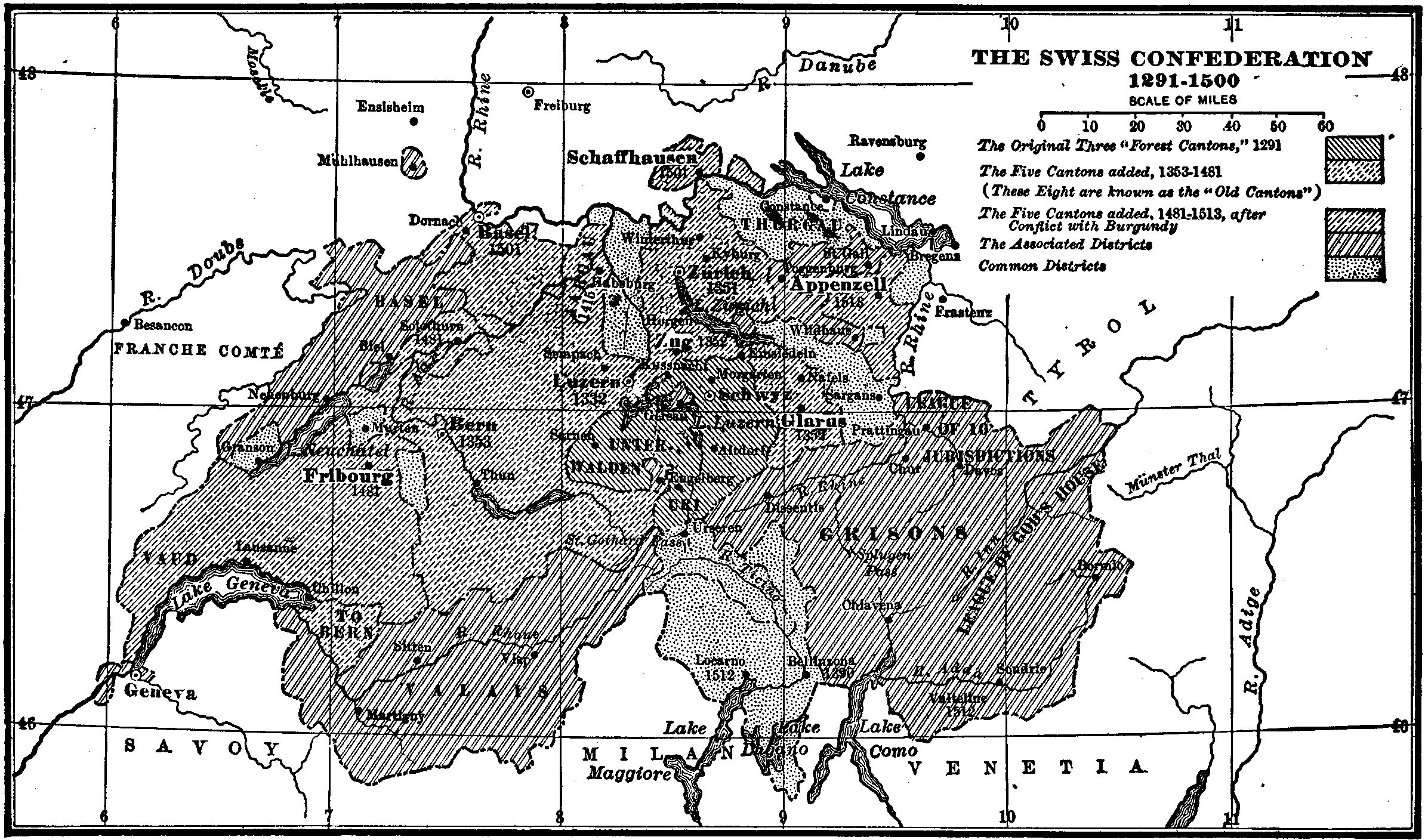

655. Switzerland. — In the mountains around Lake Lucerne there dwelt a sturdy race given to the pursuit of a simple agricultural and pastoral life. They had been under the sway of the Hapsburg dynasty long before King Rudolph. About 1300 they claimed independence, and several non-Hapsburg kings granted them the right to rule themselves and be directly under the emperor. The Hapsburg dukes refused to recognize the lawfulness of this grant. Duke Leopold advanced with a strong army of knights to enforce what he thought was his right. The brilliant army was completely routed by the peasants. The battle of Morgarten, November 15, 1315, was the birthday of Swiss liberty. In several other battles, assisted always by the nature of their rugged country, the brave mountaineers maintained their freedom, and by and by increased the number of the little “cantons” from the original three “Forest Cantons” to eight and more. (The myth of William Tell belongs to the period of Morgarten. It is a good subject for special reports.) A rather loose tie connected the cantons, each of which ruled itself independently. In 1481, when the whole alliance was on the point of breaking up, it was saved by the sudden appearance of a famous hermit, Blessed Nicholas of Flue, who within one hour settled all the difficulties. Within the Empire the Swiss Alliance ranked with the princes. It remained politically a German country until the Peace of Westphalia, 1648.

The Swiss victories, won by peasant infantry over the feudal array of armored knights, together with the battles of Legnano, Crecy, and Poitiers (§§ 559, 630, 631), mark the beginning of a new mode of warfare. The time of the mailed horseman was gone. The developments in the use of gunpowder completely sealed his fate.

The Swiss acquired fame as redoubtable warriors, whose assistance, either as allies or mercenaries, was sought by foreign powers. Many a throne was faithfully guarded by these free sons of the mountains. The last remnant of this custom is the little Swiss “arm” in the Vatican.

656. How the Hapsburg Power Grew by Marriages. —

(1) The Hapsburgs acquire the Burgundian inheritance. One of the kingdoms into which the realm of Charlemagne was finally divided was Burgundy, between the Rhone River and the Alps. This kingdom eventually became annexed to Germany (§ 556), but much of it was lost to France in the course of several centuries. To the northwest of the kingdom, there was the Dukedom of Burgundy, which had always been a French fief. There was also a County of Burgundy, which as part of the kingdom still owed allegiance to Germany. It was commonly called Franche Comte. (See the map after page 418.) Both the duchy and the county were finally united. The mighty Dukes of Burgundy found opportunities to incorporate other large provinces, in particular THE NETHERLANDS, that is, the greater part of present Holland and Belgium with some districts now belonging to France.

(The Netherlands was one of the most flourishing countries in Europe. The several duchies and counties comprised under this name contained very rich and populous cities, where merchants from Italy exchanged wares with those of the Hansa towns. It might even be said that they were rather workshops than trading rooms. “Nothing,” says one historian, “reached their shores but received a more perfect finish; what was coarse and almost worthless became transmuted into something beautiful and good.” Early in the crusading age the cities had won or bought their liberties. Each province had its diet, where sat the nobles and the representatives of the cities. Mary, the daughter of Charles the Bold, had granted them The Great Privilege (1478) which further increased their influence upon the policies of their sovereign.)

Most of these acquisitions were German fiefs. Duke Charles the Bold (1467-1477) fell in an attempt to conquer the Duchy of Lorraine, which he intended to serve as a link between the northern and the southern part of his dominions. Charles the Bold’s daughter Mary, “the richest heiress in Europe,” married Maximilian of Austria (§ 653), the later Emperor, and thereby brought her vast inheritance to the House of Hapsburg. The kings of France remonstrated. They indeed occupied the Duchy of Burgundy, but the whole rest of the inheritance went to the Hapsburgs. Next to the winning of the Archduchy of Austria (§ 650), the marriage of Mary of Burgundy with Maximilian I was a most momentous step in the development of the Hapsburg power.

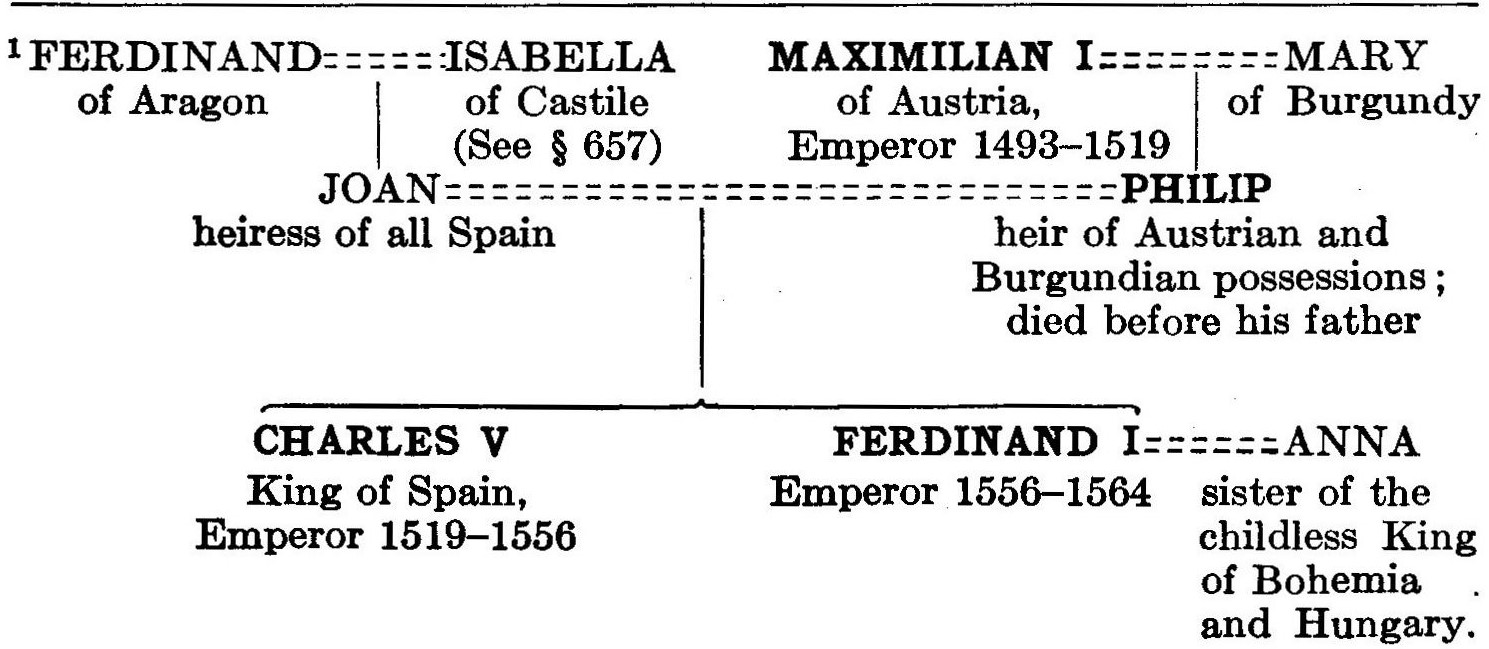

(2) The Hapsburgs acquire Spain by marriage. Philip, son of Maximilian I and Mary of Burgundy, married Joan, the daughter and heiress of the two Spanish monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella (§ 657), a marriage which brought to the Hapsburg family the crown of Spain with all the transatlantic dependencies of that kingdom in Central and South America (§ 683). Philip, who died before his father Maximilian, had two sons, Charles and Ferdinand. Charles became King of Spain by inheritance, and Emperor Charles V by election of the German electors.

(3) The acquisition of Bohemia and Hungary by marriage belongs to a later period, but may be mentioned here for the sake of completeness. Ferdinand, the brother of Charles V, received the old possessions of the House of Hapsburg, i.e., the Archdukedom of Austria with the other lands in the south of Germany. He was eventually elected Emperor Ferdinand I. By marriage with the heiress of Bohemia and Hungary he united these lands with his hereditary possessions, and thereby founded the power of his house in central Europe.

Thus the House of Hapsburg rose to the zenith of its might by the peaceful means of three marriages, all of which took place within the short space of seventy years.