The following is an excerpt (pages 527-532) from Ancient and Medieval History (1944) by Francis S. Betten, S.J. Although some information may be outdated, the Catholic historical perspective it provides remains pertinent. Use the link at the bottom of post to read the previous/following pages. Use the Search box above to find specific topics or browse using the Resources tab above.

CHAPTER XLV

THE CHRISTIAN COUNTRIES TO THE SOUTH, EAST, AND NORTH

THE STRUGGLE AGAINST MOHAMMEDANISM

657. The Spanish Peninsula. — The Mohammedan invasion of 711 A.D. (§ 422) separated the course of development in Spain from that of the rest of Europe. For a long time “Africa began at the Pyrenees.”

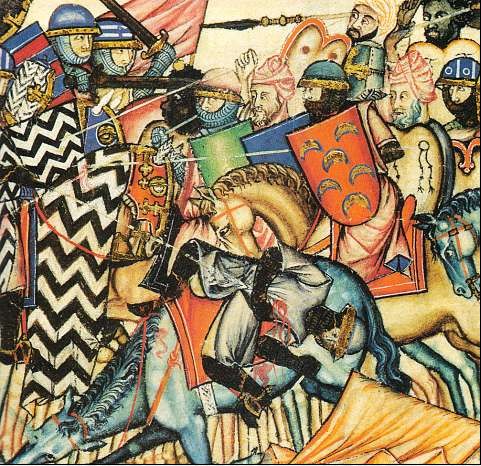

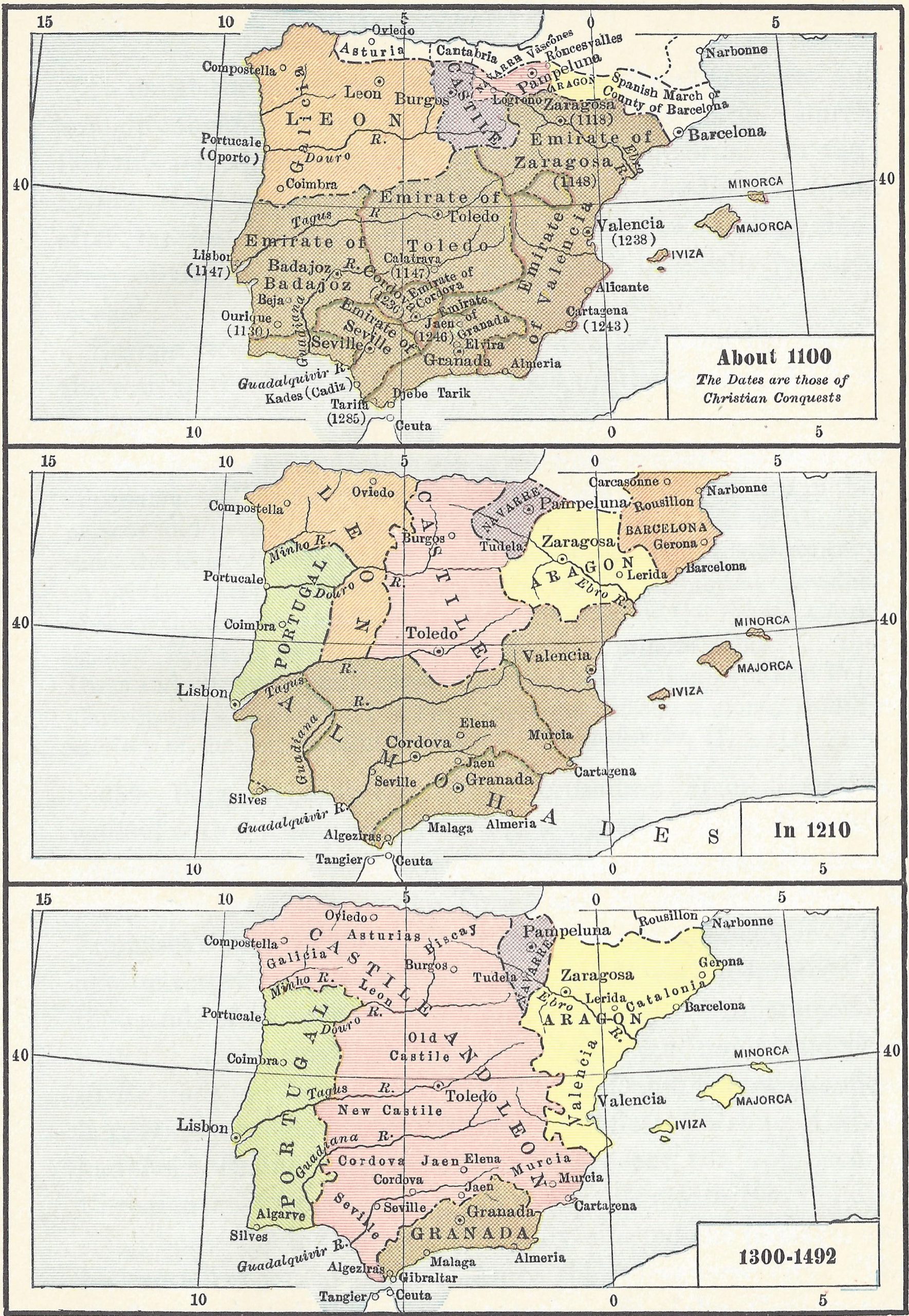

The wave of Moorish invasion, however, had left unconquered a few resolute Christian chiefs in the remote fastnesses of the northwestern mountains, and Charlemagne recovered part, also, of the northeast (§ 433). In these districts, Asturia and the Spanish March, several little Christian principalities began the long task of winning back their land, crag by crag and stream by stream. This they accomplished in eight hundred years of war, — a war at once patriotic and religious, Spaniard against African, and Christian against infidel. The long struggle left the Spanish race proud, brave, warlike, intensely patriotic, and enthusiastically devoted to the Church.

During the eight centuries of conflict, the Christian states spread gradually to die south and east, — waxing, fusing, splitting up into new states, uniting in kaleidoscopic combinations by marriage and war, — until, before 1400, they had formed the three countries, Portugal, Aragon, and Castile. Portugal remained independent. In consequence of the marriage between Isabella, heiress of Castile, with Ferdinand II, “the Catholic,” heir of Aragon (1469), the other two countries were eventually united and in later times were known as the Kingdom of Spain. In 1492 this combined power captured Granada, the last Moorish stronghold on the peninsula, and Spain at home achieved national union. In 1505 Ferdinand added the Kingdom of Naples to the Spanish domain.

Portugal as well as Spain entered upon a period of discovery and colonization which made both mighty European states (§ 683). But in European politics Spain by far outdid her smaller neighbor.

The feudal lords of the many Spanish kingdoms had been the most uncontrollable in Europe. In each petty state they elected their king, and took the oath to obey him in forms like this: “ We, who are each of us as good as thou, and who together are far more powerful than thou, swear to obey thee if thou dost obey our laws, and if not, not.”

The towns of Spain, too, had possessed charters of liberties of the most extreme character, and in various kingdoms they had sent representatives to the assembly of estates, or the “ Cortes,” for more than a century before a like practice began in England. But Ferdinand of Aragon began to abridge all these privileges, and in the next two reigns the process was carried so far that Spain became one of the most nearly absolute monarchies in Europe.

658. The Balkan Peninsula. — While the Mohammedan Moors were losing Spain, the barbarous Turks (§ 599) were gaining southeastern Europe. They established themselves on the European side of the Dardanelles for the first time in 1346. In 1361 they conquered Adrianople and made it their capital. A crusade under Sigismund, then king of Hungary, was a failure (§ 652). The Serbians and Bulgarians yielded more and more. The Greek Empire shrank to a narrow fringe along the coast in the immediate neighborhood of Constantinople. At Varna (1444) King Wladislaw III of Hungary and Poland, and Cardinal Cesarini, the papal legate, found a noble death on the battlefield.

A chief cause of these successes was the “Tribute of Children” imposed on the conquered Christians. At stated times a certain proportion of strong and promising boys had to be delivered up, to be educated in Mohammedanism and trained in the use of arms. For three centuries the janizaries, “new soldiers,” recruited in this worse than barbarous fashion, formed the most dreaded part of the Turkish army. The strength of the Christians themselves was turned against Christianity.

To enlist the assistance of the West, the Greek emperor had brought about a union of the Greek with the Latin Church. But this remedy proved unpopular on the Bosphorus. In 1453 Sultan Mohammed II entered the city of Constantine the Great, after the last emperor, likewise a Constantine, with a small army of Greeks and Latins, had defended it heroically for eight weeks.

Europe stood aghast. The popes, who had been the soul of the resistance to the Turks, again took up the defense of Christianity.

“But the apathy and selfishness of the rulers rendered united action impossible. While the popes sold the treasures of art collected in their palaces and even their own table service for the benefit of the crusade, the king of Naples spent the crusading moneys in his pleasures or on private wars; Charles VII of France (§ 639) prohibited the export of the collected sums and sent the fleet equipped by the French Church against England and Naples; the German princes talked in their Diets and intrigued against each other and against Emperor and Pope; Christian of Denmark and Norway stole the crusading money from the sacristy of the cathedral of Roskilde.” Guggenberger, II, § 115.

659. Pope Calixtus III, of the crusading Spanish nation, worked with untiring energy for a new crusade. John Hunyady, administrator of the Kingdom of Hungary, who had for many years been warring with the Turks, and St. John Capistrano, a Franciscan friar, whom the Pope had sent out as preacher of the new enterprise, collected an army which was reenforced by thousands of Frenchmen, Germans, and Poles. Mohammed II, with the same army that had reduced Constantinople, laid siege to Belgrade on the southern bank of the Danube, now the most important stronghold of Christianity. A fleet, the ships of which had been chained together, was to prevent the approaching Christian host from crossing the river. But with two hundred small boats the indomitable Hunyady effected the passage, and his crusaders joined the garrison of the beleaguered city. The Turks continued their fierce attacks. St. John Capistrano’s addresses kept up the courage of the Christians. Finally a desperate sortie drove the Mohammedans into a headlong flight with the complete loss of their camp and most of their artillery, August 6, 1456. (The Sultan’s sumptuous tent was sent to the Holy Father, Pope Calixtus III. To commemorate this victory, the feast of the Transfiguration was instituted, to be celebrated in the whole Church on August 6.) The two heroes of this success, John Hunyady and the saintly Franciscan friar, died soon after.

During the same time the little country of Albania was saved for a generation by a handful of mountaineers under their invincible leader George Castriota, commonly called by his Turkish epithet, Scanderbeg (Prince Alexander).

Dissensions among the Turks under less warlike sultans gave some periods of respite to the Christian nations. The popes meanwhile endeavored to strengthen the resistive power of Hungary, until the greater part of that country, too, in 1522 succumbed for a time to the Crescent. Unable to assimilate European civilization, the Turks remained like a hostile army encamped among subject Christian populations, and their baneful influence blighted and largely destroyed the ancient culture of many a conquered land.

THE COUNTRIES TO THE EAST AND NORTH

660. Poland, Prussia, Lithuania. — Poland had recovered from the helpless condition in which we found her at the beginning of the thirteenth century (§ 597). The Teutonic Knights now possessed a strong, well-ordered state between the Baltic Sea and Poland. But grave charges began to be raised against them. They insisted with rigor, nay cruelty, upon what they called their rights, and failed to respect Polish territory. In the course of the fourteenth century numerous frictions led to an ever-increasing enmity between the two neighbors. The intervention of vigorous popes, no doubt, would have prevented much of the dissension and removed many causes of hostility. But this was just the period of the unfortunate Western Schism with all its disastrous effects upon the general interests of Christianity. (See the map after page 480.)

East of both Poland and Prussia was the country of the Lithuanians, still practically pagan (§ 600). The Lithuanians and the Knights were regarded by Poland as her hereditary foes.

In 1386, however, Princess Hedwig, the heiress of the Polish crown, consented to marry Jagello, the chief of the Lithuanians, on condition that he with his whole nation should become Christian. This momentous fact united the two countries under one king, now called Wladislaw II, against the Teutonic Knights. The war, long evaded by the Knights, finally broke out. In 1410 the Knights were completely defeated in the battle of Tannen- berg (west of Kulm). This battle marks the downfall of the Teutonic Order. Fifty years later (1466), after another disastrous war, the Grand Master was forced to cede the land west of the Vistula to Poland, receiving the eastern portion as Polish fief. This is the first great “secularization” of ecclesiastical territory on record.

The Poles have reason, from the national standpoint, to celebrate the victory of Tannenberg. From the standpoint of the Christian we must regret the robbery thus committed by a Catholic power. To some extent, however, it can be excused. The Knights had by this time lost the purpose for which their order had been originally established. Several attempts to find another field where they might serve the cause of Christianity with the sword had failed — not without their own fault. During the period of prosperity religious discipline within the order had suffered greatly. The Prussian cities, justly or unjustly, complained of oppression, and made common cause with the Poles. The kingdom of the united Poles and Lithuanians, on the other hand, had to fulfill in due time a providential mission; namely, to assist valiantly in the defense of western Europe against the Turks.

661. Scandinavia had sent the Northmen into all parts of Europe (§ 450 ff.). After the formation of the three kingdoms of Denmark, Sweden, and Norway a complete Christian hierarchy of bishops and archbishops kept in touch with Rome and the ecclesiastical life of the continent. But after the dissolution of the brief empire of Knut the Great (§ 502), Scandinavia took no prominent part in European politics. The story of these northern lands is romantic. The very names of the Norse kings make a portrait gallery, — Eric Broadax, Hakon the Old, Hakon the Good, Olaf the Thickset, Olaf the Saint. In 1397 the three kingdoms were united under Queen Margaret of Denmark by the Union of Calmar, which left to each realm its own laws and administration, but placed the management of all foreign affairs in the hands of the Danish ruler. In practice the two states of the northern peninsula became dependencies of Denmark. Both Norway and Sweden rebelled several times. In 1521 Gustavus Wasa succeeded, after a career of daring adventures, in freeing Sweden, which elected him hereditary king. Norway remained united with Denmark until 1815.