The following is an excerpt (pages 196-199) from Ancient and Medieval History (1946) by Francis S. Betten, S.J. Although some information may be outdated, the Catholic historical perspective it provides remains pertinent. Use the link at the bottom of post to read the previous/following pages. Use the Search box above to find specific topics or browse using the Resources tab above.

CHAPTER XX

CONQUEST OF THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

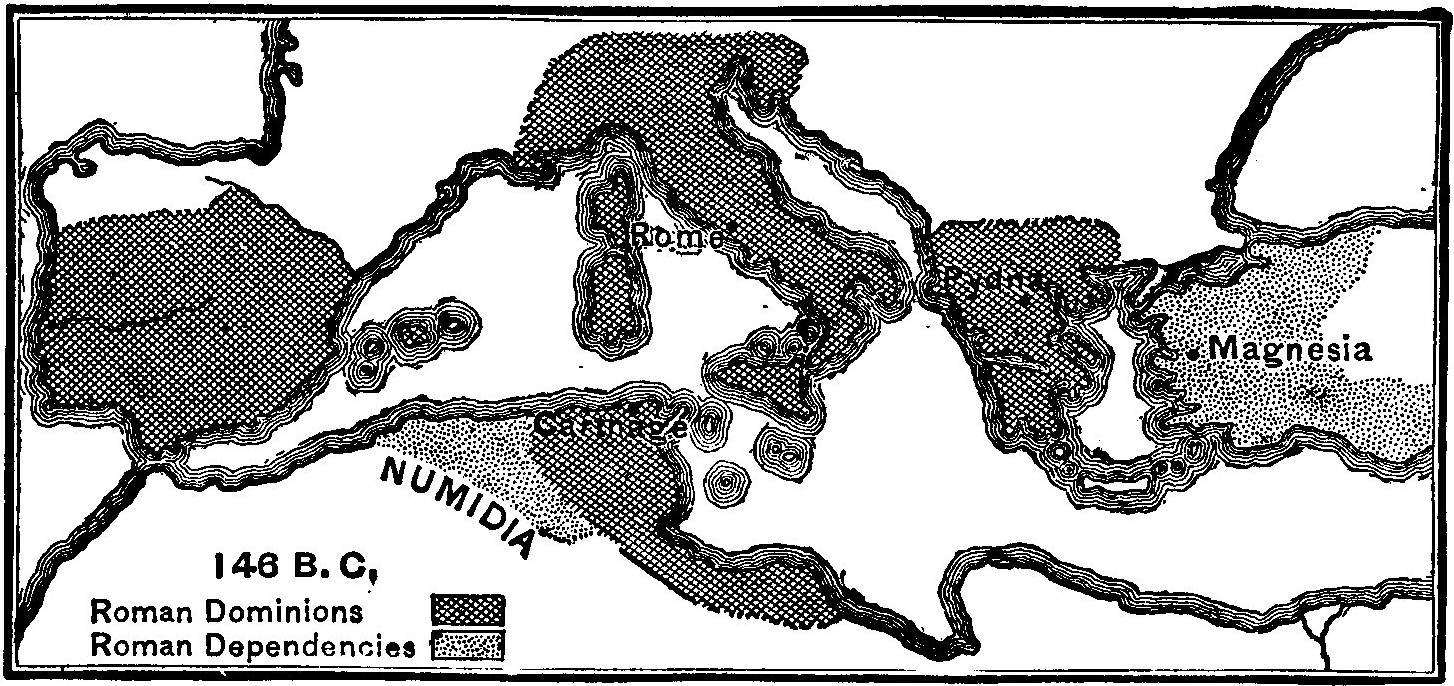

We have seen how the conquest of the western lands of the Mediterranean was continued and, in a way, finished during the half century following the Second Punic War. During the same half century Rome also strenuously began the conquest of the lands on the eastern part of that sea. These wars we shall have to study now. The great powers in the East were Macedonia, Syria, and Egypt. The Romans never fought a war with Egypt. This rich country fell their prey in consequence of a series of wars with the two other states, Macedonia and Syria.

248. First Macedonian War.—When the Romans victoriously attacked the Illyrian pirate states (§ 237), the King of Macedonia, Philip V, began to realize that after some time the aggressive Italian commonwealth might come to attack his own power also, especially since Rome was already in friendly relations with some Greek cities. So during the Second Punic War he joined Hannibal. The Romans, through their Greek allies, waged against him the First Macedonian War. It closed before the end of the Second Punic War without much gain or loss.

249. The Second Macedonian War, 201—196, was all of Philip’s making, though it was welcomed by the politicians and the money men of Rome. Philip attacked Greek cities which were Rome’s confederates, and with King Antiochus of Syria planned a division of territory belonging to Egypt, a country with which Rome also had an alliance. The war dragged on for several years because of the inability of the generals. But when Flamininus, a friend of Scipio, the conqueror of Zama, was appointed leader, fortune turned. In the battle of Cynoscephalae (Dogs’ Heads) Philip was decisively defeated. His phalanx could not stand against the flexible array of the Roman legions. Philip V had to diminish his army to 5000 men, deliver up all but ten of his warships, and confine his power strictly to Macedonia. This country was now a second-rate power. Flamininus declared all the Greek states “free,” which meant that Rome controlled the foreign relations of each of them. Rome annexed no territory for herself.

250. The war with Syria, 192—189, was similarly brought on by the aggressions of Antiochus III against Egypt and Greece. The blunders of Antiochus and the excellent generalship of Lucius Scipio, who was assisted by his brother, the victor of Carthage, made this war a brilliant success for the Roman arms. The decisive battle was fought at Magnesia on the coast of Asia Minor. Again Rome took no territory. Antiochus III had to pay an enormous war indemnity, reduce his army, and give up large provinces to the smaller states in Asia Minor, which became Rome’s allies. Syria was no longer to be feared.

251. The Third Macedonian War, 171—168. — By his endeavors to shake off the restrictions imposed by the Romans upon Macedonia, Perseus, son of Philip V, provoked a new war. He found allies among the Greeks, who felt that their “freedom” under Roman control did not permit them their ceaseless warfare with one another. The battle of Pydna sealed Macedonia’s fate. Perseus was carried to Rome as prisoner. His land was divided into four “independent” republics under Roman supervision. When these made another attempt to restore the old monarchy, the Romans annexed the land and organized it into the first Roman province in the East.

252. War with the Greek States. — A severe punishment was inflicted upon those Greeks who had openly sided with Perseus or had not given the Romans that whole-hearted support which they expected. Some twenty years after the battle of Pydna the Achaean League, practically alone, renewed the war against Rome. The end was to be foreseen. Chiefly at the instigation of the merchant class, Corinth was completely destroyed in the same year in which Carthage sank in ashes, 146. The Greek cities still retained a vestige of home rule with the aristocrats in power. For a time the Roman governor of the province of Macedonia controlled Greece also. Later it became a separate Roman province under the name of Achaia.

253. Further Conquests. — Among those states which had been favored after the war with Syria (§ 250) was Pergamum, which indeed included a considerable part of western Asia Minor. The King of Pergamum, to keep himself in possession of his power while he lived, willed the land to Rome. Upon his demise Rome made it into a province under the name of Asia. There existed also a confederacy of Rhodes, which through all the wars had faithfully assisted the Romans. Now her services were no longer needed, but her trade was an obstacle to the enterprises of Roman financiers. Rome was mean enough to deprive her of her little power and to throttle her commerce. The island remained, however, a foremost seat of learning for many centuries more.

254. Retrospect of the Century of Conquest, 264—146. — We should realize the magnitude of the Roman achievements during this period. When the First Punic War began, Rome was one of five world powers. (See beginning of chapter XIX, page 186.) Now she was the only one. Carthage and Macedonia were no more. Syria was dependent and helpless. Egypt was in submissive alliance with the Queen of the World. The most utopian political dreams had become a reality. The spoils taken from Hellenic and Macedonian cities were so enormous, and the tributes from provinces and other “confederates” so ample that taxation of citizens could be stopped. The fabulous success produced an unbounded pride, and increased the old Roman selfishness and brutality.

Yet the Roman rule was not without great benefits to the conquered. Above all, the wars, large and small, that had torn the Mediterranean world, with all their destruction of life and goods and happiness, were now a thing of the past. Rome settled all disputes between her “subjects” — fairly and justly, too, unless the interests of the lords on the Tiber were at stake. Rome extended to the newly conquered lands her system of roads and saw to it that these were safe for travel.