The following is an excerpt (Chapter IV, pages 19-24) from Ancient and Medieval History (1946) by Francis S. Betten, S.J. Although some information may be outdated, the Catholic historical perspective it provides remains pertinent. Use the link at the bottom of post to read the previous/following pages. Use Search to find specific topics or browse using the Resources tab above.

CHAPTER IV

EGYPT

THE LAND AND ITS INHABITANTS

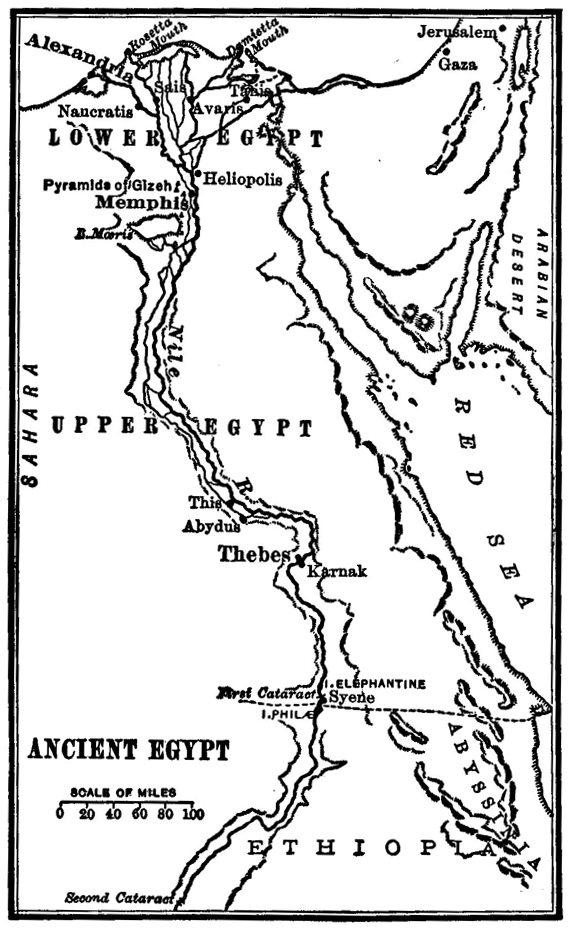

10. The Land and the River. — The real Egypt is composed of a narrow valley averaging not more than ten miles in width, through which runs the Nile River, and the triangular Delta at the several mouths of the river. The valley itself is called Upper Egypt, which is thought to begin at the first cataract. The Delta is known as Lower Egypt. It has been built up out of the debris and mud carried down in earlier periods by the Nile and deposited upon the old sea bottom.

In this narrow valley and on the broadening Delta lay all the numerous cities and villages. Let the student locate on the map the chief cities, especially Memphis, the capital of Lower Egypt, and Thebes, the capital of Upper Egypt.

Rain rarely falls in Egypt. There are eight practically rainless and cloudless months, toward the end of which the land seems gasping for moisture, “only half alive, waiting for the new Nile.” But in July the river begins to rise, swollen by tropical rains at its upper course in distant Ethiopia, and it does not fully recede into its regular bed until November. While the flood is at its height, Egypt is a sheet of turbid water, spreading between two lines of rock and sand. As the water retires, the rich loam dressing, brought down from the hills of Ethiopia, is left spread over the fields, renewing their wonderful fertility from year to year; the long soaking supplies moisture to the soil for the dry months to come. We now understand why the Greeks called Egypt the “Gift of the Nile.”

11. The Inhabitants. — Egypt is far away from the place where, after the Deluge, the new mankind began its existence.

It was even separated from those cradle lands by barriers of desert and water. Yet, our natural sources of information show

that as early as five thousand years before the coming of Christ there was living in Egypt a numerous population, well versed in most features of civilized life. Over what roads they journeyed to the land of the Nile will probably never be discovered. The Egyptians known to history were a sturdy race, exhibiting a definite type of men, which has remained to the present day. During the greatest part of her several thousand years of history Egypt was ruled by one government, and there existed also, in spite of provincial differences, a pretty well marked national unity in language, religion, and customs.

GOVERNMENT AND PEOPLE

12. The King and the Higher Classes. — The Egyptians, like all other Oriental nations, knew nothing of the republican form of government. They were ruled by a king, whom they worshiped as a god. His title, Pharaoh, means The Great House, implying that the ruler was to be the refuge for his people.

The pharaoh was the owner of the soil. This made him absolute master of the inhabitants, though in practice his authority was somewhat limited by the power of the priests and by the necessity of keeping ambitious nobles friendly. Part of the land he reserved for his own use, to be cultivated by peasants under the direction of royal stewards. The greater part he parceled out among the nobles and the temples.

In return for the land granted to him, a noble was bound to pay certain amounts of produce, and to lead a certain number of soldiers to war. Within his domain the noble was a petty monarch. Like the king he held part of his land in his own hands, and let out other portions to lesser nobles, who were dependent upon him much as he was dependent upon the king.

About a third of the land was turned over by the king to the temples to support the worship of the gods. This land became the property of the priests. The priests were also the scholars of Egypt, and they took an active part in the government. The pharaoh chose most of his high officials from them, and their influence far exceeded that of the nobles.

13. Officials and Soldiers. — For the service of the state the king needed many officials, who were organized in grades like the officers of an army. Especially the collection of taxes required large numbers of public servants. Until the seventh century B.C. the Egyptians had no money, and the immense royal revenues had to be paid “in kind.” Cloth, metals, jewels, grain, wine, oil, cattle, geese, ducks — “all that the heavens give, all that the earth produces, all that the Nile brings from its mysterious sources,” as one king puts it in an inscription, were delivered into the royal treasury. To receive and register and care for all this required an army of royal officials. The great nobles, too, for a like reason needed a large class of trustworthy servants.

The soldiers formed an important profession. Campaigns were so deadly that it was hard to find soldiers enough. Accordingly recruits were tempted by offers of special privileges. Each soldier held a farm of some eight acres, a large farm for Egypt on account of the fertility of the soil. He was free from taxes, and was kept under arms only when his services were needed. Besides this regular soldiery, the peasantry were called out upon occasion for war or for garrison duty.

14. The Lower Classes. — In the towns there was a large middle class, made up of merchants, shopkeepers, physicians, notaries, builders, artisans of every kind, and below them all the unskilled laborers. These latter would sometimes resort to a strike to obtain better laboring conditions, as laborers do in our own days.

On one occasion we are shown the workmen turning to the overseer, saying, “We are perishing of hunger, and there are still eighteen days before the next month.” (Rations were allowed at the end of the month.) The overseer makes profuse promises. When nothing comes of them, the workmen will not listen to him any longer. They leave their work, and gather in a public meeting. The overseer hastens after them, and the police commissioners of the locality and the scribes mingle with them, urging upon the leaders to return. The workmen only say, “We will not return. Make it clear to your superiors down below there.” The official who reports the matter to the authorities seems to think the complaints well founded, for he says, “We went to hear them, and they spoke true words to us.”

The peasants were not unlike the peasants of modern Egypt. They rented small farms, for which they paid at least one third of the produce to the landlord. This left too little for the support of a family. It became necessary for them to increase their revenue by working as day-laborers in the fields of the nobles and priests. For their labor they were paid “in kind,” that is, by receiving a certain amount of grain and other produce.

Throughout Egyptian society the son usually followed the father’s occupation, but he was not obliged to do so. Sometimes the son of a poor herdsman rose to wealth and power. Such advance was most easily open to the scribes. From the ablest scribes the nobles chose confidential secretaries and stewards, and some of these who showed special ability might be promoted to the highest dignities in the land.

15. Life of the Wealthy. — For most of the well-to-do life was a very delightful thing, filled with active employment and varied with many pleasures. Their homes were roomy houses, consisting of wooden framework plastered over with sun-dried clay. Light and air entered at the many latticed windows, where, however, curtains of brilliant hues shut out the occasional sand storms from the desert. About the house stretched large gardens with artificial fishponds gleaming among the palm trees. In these households women held a very honorable position, much more so than in any other ancient nation except the Jews. (The same is true of the women in the families of the less fortunate classes.)

16. The life of the poor, too, does not seem to have been void of pleasures. In many places they were the object of marked consideration on the part of the rich. As will be seen later on, the Egyptians had saved much of the original religious knowledge of mankind. “I have not despoiled the poor and widows and orphans,” is one of the consolations put into the mouth of deceased persons. There was, moreover, not the misery of extensive slavery, because Egypt had few slaves. Generally speaking, Egypt believed in free labor, though the freedom had narrower limits than with us. The lower working classes lived in unhealthy mudhovels, in the villages or the outskirts of the cities, sometimes a whole family in one room. There was little sewerage, if any. The streets were covered with filth, and only the exceedingly dry climate kept down pestilences. Often without their fault, often through lack of frugality and foresight — even ample provisions were consumed within a short time — the poorer people found themselves in direst need, especially at the time when the tax collector came around. On such occasions, the whip was freely employed, as was also the case in the forced labors on pyramids and canals. Still, judging from Egyptian literature, the peasants must have been happy-go-lucky folk, gay and careless, too much so, playing with their cattle, and enjoying themselves by singing even at their work.