The following is an excerpt (pages 84-100) from Ancient and Medieval History (1946) by Francis S. Betten, S.J. Although some information may be outdated, the Catholic historical perspective it provides remains pertinent. Use the link at the bottom of post to read the previous/following pages. Use the Search box above to find specific topics or browse using the Resources tab above.

CHAPTER X

A PERIOD OF PROGRESS

The preceding age had been a period of storm and stress. The next great period we are going to study now will not be without quarrels and bloody wars among the many little independent communities of Greece. We shall briefly mention the more important of these contests. We shall lay the main stress upon the institutions, customs, and other cultural features of the Hellenes. We want to learn what kind of people they were.

We shall have to consider six great movements, (1) The Hellenes awoke to a feeling that they were one people as compared with other peoples. (2) They extended Hellenic culture widely by colonization. (3) The system of government everywhere underwent great change. (4) Sparta became a great military power, whose leadership in war the other Greek states were willing to recognize. (5) Athens became a democracy. (6) A great intellectual development appeared, manifested in architecture, painting, sculpture, poetry, and philosophy.

NATIONAL UNITY

89. The Greeks imagined themselves to be the descendants of one man, Hellen, the first inhabitant of Hellas. The Achaeans, Dorians, Ionians, and a fourth obscure tribe, the Aeolians, they thought were named after his sons or grandsons. They all could converse in one language. Though the beautiful Greek tongue was not spoken in exactly the same way in every region, all the Hellenes could understand it, and all the works produced in it in any part of the Hellenic world at once became common property. The Greeks felt proud of their language. They looked with contempt upon all those nations who did not know it. They called them ” barbaroi,” barbarians (babblers), however

educated they might be, e.g., the Egyptians or Phoenicians. All the Hellenes, moreover, believed in the Olympian religion, as propounded by their great poet Homer, and worshiped the same gods and goddesses. Thus a fictitious common descent, a common language and a common religion distinguished them from all other nations, and caused them to entertain a racial pride and a sort of common patriotism. Several institutions, chiefly based on religion, increased this feeling of national unity.

A restoriation. At the left the round Philippeion, erected by Philip II (§ 171); next the Temple of Hera, the oldest stone temple in Greece; the high Niche of Herodes Atticus (died 180 A.D.), containing fountains; between it and the large Temple of Zeus, the treasuries holding donations of cities and articles used in the contests.

90. The Panhellenic Games. — In honor of certain gods great religious festivities, sacrifices, etc., were celebrated in particular places and at stated times. With these were connected contests in athletics — foot races, chariot races, wrestling, and boxing. All Hellenes, from whatever place they came, and only they, could compete in them. These games commonly drew immense crowds from all parts of the Hellenic world. Here the Hellenes saw themselves really as one people. Here merchants offered their wares. Heralds proclaimed treaties. Although the victor received only a wreath of olive leaves or of grass, he was a famous man. His city would receive him in a triumphal procession and celebrate his victory by inscriptions and statues. Especially famous were the Olympic Games, celebrated every fourth year at Olympia in the Peloponnesus. Very soon contests in poetry and other arts were added. Gradually these intellectual contests became the chief feature, though no prize was given to the winner. (See D. R., I, No. 44; and H. T. F., “Olympiads.’’)

91. The Oracles. — The Greeks believed that the gods in certain places revealed the future, or gave directions in the conduct of affairs. These places were called oracles, as were also the answers returned by the gods. Remarkably famous was the Oracle of Apollo, the special god of prophecy, at Delphi. From a fissure in the ground volcanic gases poured forth. Over it a tripod was placed for a priestess to sit on. The gases would soon reduce her to a state of frenzy, in which she uttered words or inarticulate sounds. The priests made up an answer from these sounds for the questioner. Sometimes they gave good advice. When the matter was doubtful to them, they returned evasive or ambiguous replies. The oracles, especially the Delphic, enjoyed great popularity. Private men as well as governments often applied to them in their difficulties.

COLONIZATION

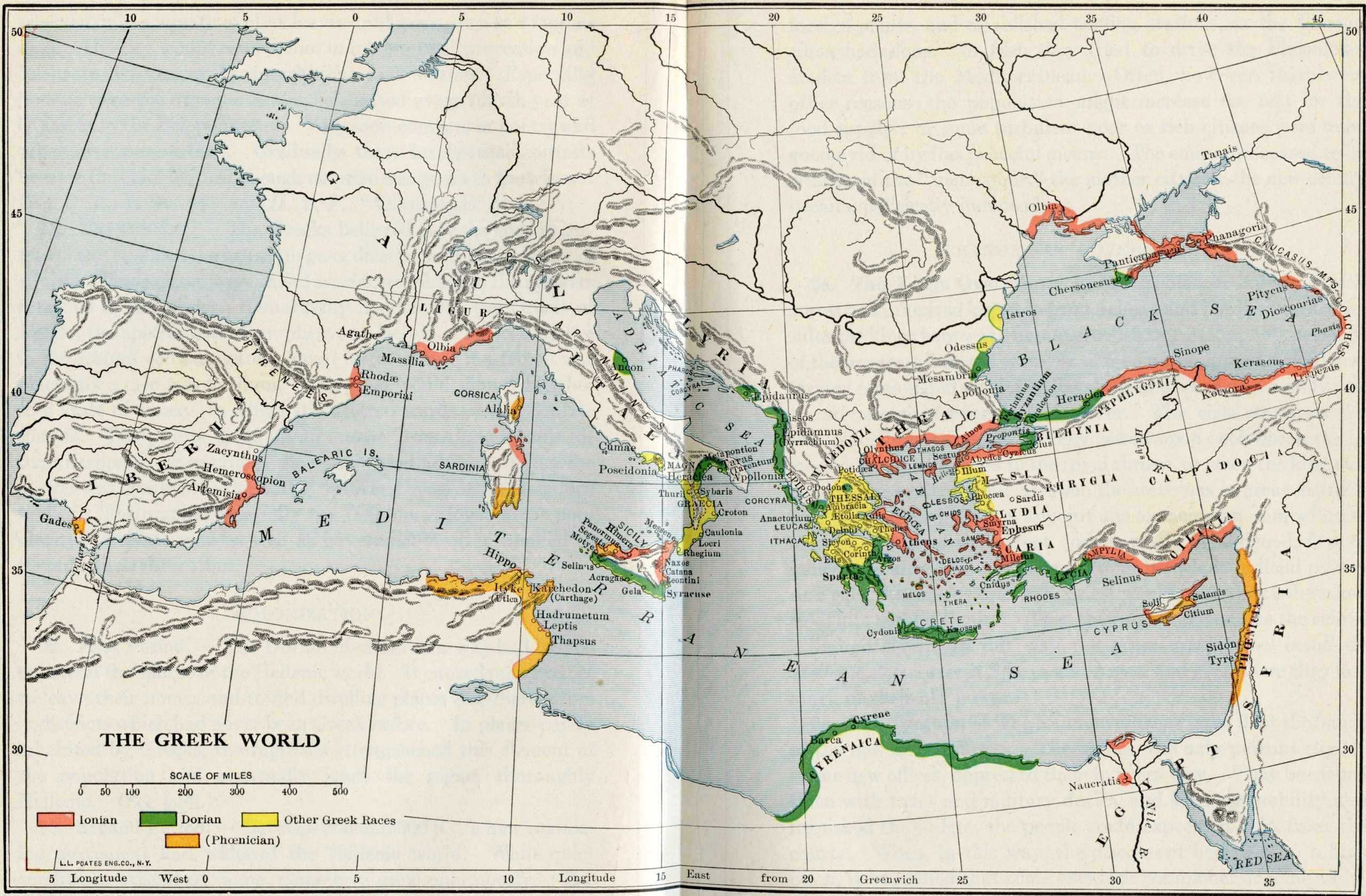

92. First Period. — The Dorian invasion in a way had helped to extend the sphere of the Hellenic world. It caused many tribes to leave their homes and to find dwelling places elsewhere, often in districts which had never been Greek before. In places partly inhabited by Greeks, the fugitives strengthened this element of the population and eventually made the region thoroughly Hellenic. (See § 88.)

93. Second Period. — Between 800 and 600 B.C. a new colonizing movement had widened the Hellenic world. While quiet conditions existed at home, commerce grew enormously. The more powerful cities looked for securing the trade at certain foreign points, and established trading stations, as the Phoenicians had done. In fact, they tried to drive the Phoenician traders from the Mediterranean. Often, however, there were other reasons: the population might increase too fast for the food supply; or some turbulent poor or rich citizens were to be gotten rid of by this peaceful means. The emigrants ceased to be citizens of the “metropolis,” the mother city, for the new colony became politically independent.

CHANGES IN GOVERNMENT

94. The Kings Overthrown by the Nobles. — All the Greek states had inherited kingship from Achean and Dorian times. Besides the king there was a nobility, consisting perhaps of the heads of the former tribes and clans, or of men whose ancestors had performed some signal service to the state, or of such who merely had the advantage of riches in their favor. This class strove for the first place in government. They seized upon such occasions as when a minor succeeded to the royal throne, or when the king was disliked for arbitrariness, or when the state was in great distress. They would, for instance, appoint one of their own number commander of the army. Next, judges would be assigned, first to relieve the king, and then to take over his whole judicial power. As a rule, the king’s position as priest would be the last to be taken from him and his family. Thus the rule of one became the rule of a limited class. In this way the kings disappeared in all the Hellenic states, except Sparta and Argos, and even there they lost much of their old power.

95. The Tyrants. — The common citizens fared ill at the hands of the new governments. The nobles, the only persons eligible to the new offices, oppressed them in every way. They burdened them with taxes and military duties, and since the nobility also furnished the judges, the people could expect no help from the courts. When, in this way, the discontent had risen to a high pitch, it happened that some energetic commoner or some ambitious noble put himself at the head of the masses, overthrew the government of the nobles, killed or exiled the officials, and began to rule the state himself. Such men the Greeks styled tyrants. This name did by no means imply that they all ruled in what we now call a tyrannical manner. On the contrary, since they had risen by the people, they were bound to govern for the people. Commonly, they put more burdens upon the nobles, and had the dangerous ones executed or banished. Many of these tyrants were able rulers, who built harbors and roads, erected public buildings, and patronized art and literature. Before 500 B.C. every city on the peninsula had such a tyrant or had had one. In the other parts of Hellas, tyrants are met with at later periods also.

One reason for the disappearance of the tyrants was the general dislike of the Hellenes for one-man rule. Very often, too, the tyrant, though perhaps in the beginning a good ruler, had recourse to acts of gross injustice and violence, thus justifying the meaning which we now attach to that word. The party of the nobles could always represent him as an enemy to popular liberty. Any gross blunder on his part, together with their own intrigues and secret and open propaganda, would undermine his personal popularity and lead to his expulsion or death. Yet the nobles had been weakened in the whole process, and the people had gained confidence. In Ionian cities generally a democracy followed; in the Dorian states an aristocracy, though on more liberal lines. Thus the tyrants unintentionally prepared the way for a government by the people.

THE STATE OF SPARTA (LACONIA)

96. Early History — The Dorians had chiefly settled in the Peloponnesus. At first they formed a large number of petty states, which in the course of a rather short time consolidated into several larger ones (page 102). The one called Laconia eventually obtained the headship, inasmuch as all the other states, with the exception of Argos, became its allies. Messenia, west of Laconia, was conquered and its inhabitants reduced to a state of slavery. The city of Sparta was the capital of Laconia. The people thought that a man named Lycurgus had established all their institutions, though it is more probable that these developed gradually. After they were once fixed they remained unchanged for five hundred years.

97. Classes of Society. — The ruling class in Laconia was the Spartans. They were professional soldiers, either at war or preparing for war. They did not work. Their farms, the best in the land, were worked by a class of slaves, the Helots. The Helots, much more numerous than the Spartans, were the property of the state, not of individuals. The harshness with which they were treated made them a danger for the state. When they increased too much in numbers, whole crowds of them would often vanish in some mysterious way. In fact, it was no crime to kill a Helot without reason. The loss of one Helot was hardly felt by the state, and was no loss at all for the individual.

A third class, the Laconians, owned farms of moderate size. They were free, and could engage in commerce if they so pleased, but they had no part in the government. In war they served as heavy-armed infantry. Generally they seem to have been well treated and well content.

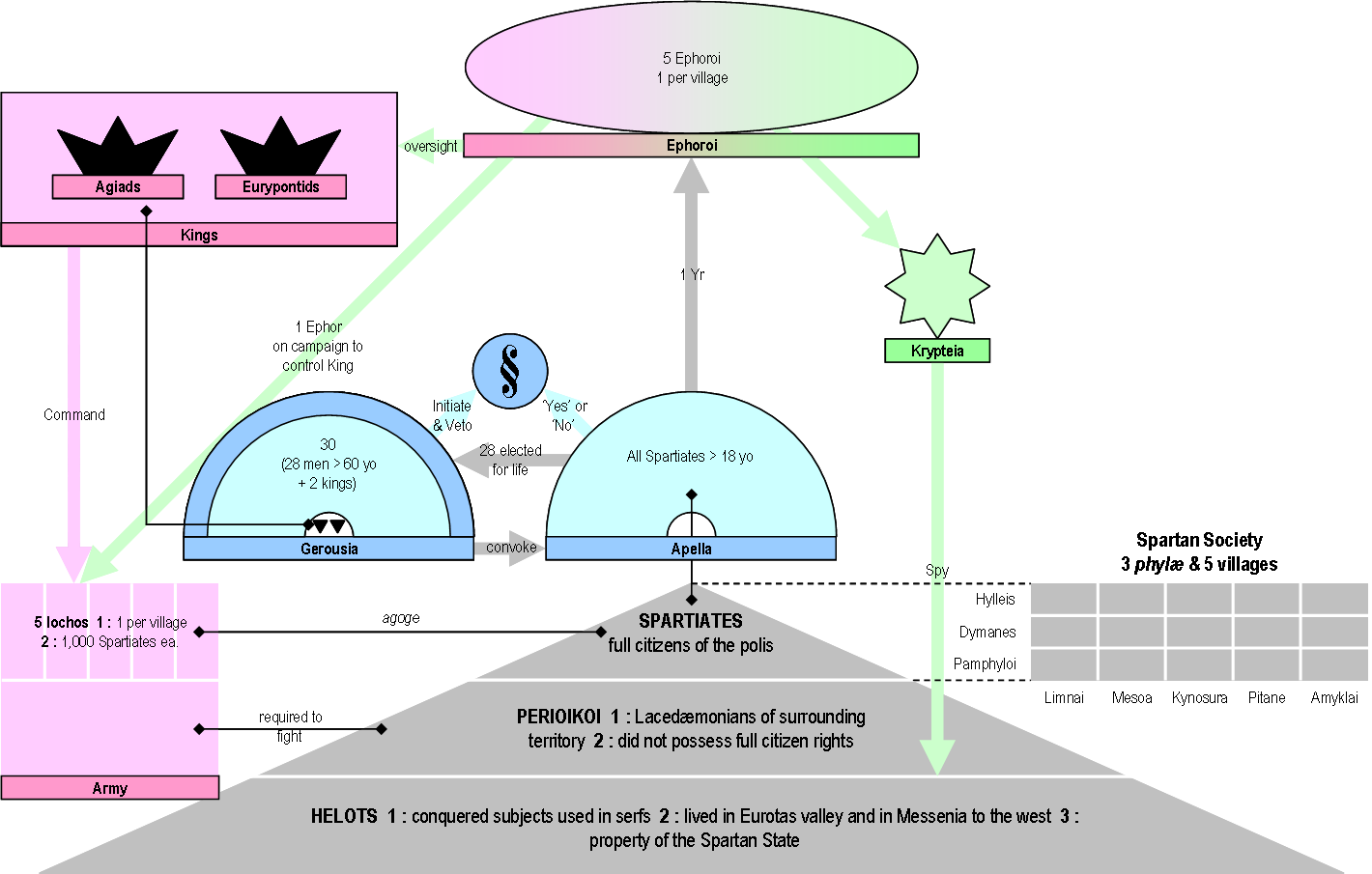

98. The Government. — Sparta had two kings. An old legend explained that this peculiar arrangement was due to the birth of twin princes. At any rate, the kings had very little power, though they enjoyed some honor.

The government, itself, consisted of three parts: the Senate, the Popular Assembly, and a group of five magistrates called the ephors. The Senate was made up of thirty senators, each over sixty years of age. This body was the most important force in the government, for they alone could introduce new measures or propose new laws. The Popular Assembly consisted of all the Spartans. They chose the senators, elected the ephors, and had the privilege of voting Yes or No on all governmental questions. The ephors appeared about 725 B.C. They were selected each year and any Spartan might be chosen. They called the Assembly, presided over it, and acted as judges in all important matters. One or two of them accompanied the king in war, with the power to control his movements, and even to arrest him and put him to death, if they thought it necessary. In practice, the ephors acted as the servants of the Senate.

99. Spartan Discipline. — The sole aim of the famous Spartan discipline was to make soldiers. This it did; but it was harsh and brutal, and in some points criminal.

The Spartan belonged first to the state and then to the family. The ephors examined each new-born boy. If he appeared too weak to make a good warrior, he was exposed on the mountains to die. Otherwise he was left to the parents for seven years. After that age the boy never slept under his parents’ roof. He lived with other boys in barracks to be educated by public masters, who taught him reading, a little martial music, and accustomed him to show respect for his elders. They gave him no mental or cultural training, but plenty of athletic exercises. On certain days the boys were whipped at the altars to test their endurance. It is said that some would rather die than utter a cry. At twenty the young man became a regular warrior, and lived in the barracks where he was one of a mess of fifteen. His whole time was given to military drill. At thirty he was required to marry, but he still ate with his companions in the barracks. He had no real home.

The Spartan built his house with no other instrument than ax and saw. He did not possess any gold or silver. To keep him from engaging in commerce, the state minted only iron money. In contrast with the noisy Greeks all around, his speech was brief and pithy (“Laconic”). Once the mighty King Philip of Macedonia wrote a long letter to the Spartans threatening them, “when I come to Sparta, you will be sorry for your resistance, etc., etc.” Their whole reply was, “when.” The girls received a training similar to that of the boys. The women were famous for beauty and health, and for public spirit and patriotism.

It is no wonder that with institutions like these the Spartans did nothing for arts and sciences of any kind, though by their military prowess they helped to save Greek culture from foreign foes.

THE STATE OF ATHENS (ATTICA)

GOVERNMENT BY NOBLES

100. The Eupatrids. — The little peninsula of Attica had been spared the terrors and changes caused by the Dorian invasion. Its population had increased greatly (§ 88). Through peculiar circumstances, the whole state had become thoroughly consolidated. Every man living in Attica was thought of as a citizen of the capital, Athens. Although the country was ruled by a king, there was a numerous nobility, — consisting chiefly of the heads of the several clans — called the eupatrids (“well-born”), who acquired more and more powers. As explained in § 94, they finally dislodged the king. From their own number they elected nine archons to attend to the functions formerly performed by the king. The eupatrids thus ruled the state. The assembly, the Areopagus, was closed to all the other citizens. Had they otherwise treated the people fairly, all the citizens might have put up with their domination. However, since the eupatrids owned nearly all the land, they demanded very high rents from their numerous tenants. In case of a bad harvest or hostile ravages, the tenants were forced to borrow seed and food, which they frequently found impossible to return at the stated time. In this event the law, made by the eupatrids themselves, allowed the creditor to take everything the debtor possessed, and even to sell him, his wife, and children into slavery. We can understand how, under these circumstances, there grew up a bitter dissatisfaction and a feeling of revolt.

101. Introduction of the Four Classes. — A little change for the better came when Attica adopted the Dorian method of fighting by forming the heavy-armed infantry, the “hoplites” (§ 88). So far the eupatrids, as heavy-armed cavalry, had been the main force in war, while the infantry amounted to very little. Since every soldier had to supply himself with arms, only the richer citizens could be expected to serve as hoplites. So the whole population was divided according to their landed possessions into four classes, the first two to serve as knights or cavalry, the third as hoplites, and the fourth, which was rarely called out, as light-armed infantry. Thus it could happen that the rich commoners were enrolled in the second or first class, while poorer eupatrids sank into the second. It was natural that the new classes should also decide the question of war and peace. A new assembly of the classes was formed, excluding, however, the fourth class. Gradually other matters, too, came before this assembly instead of the Areopagus. The greatest privilege of the eupatrids, noble birth, gave way before the principle of landed wealth, a fact which could not but strengthen the self-confidence of the lower classes. For the time being, it is true, the eupatrids continued to hold the real power, but the first step towards democracy had been made.

There followed a rather rapid succession of political changes in Athens, which were connected with the names of four men: Draco, Solon, Pisistratus, and Clisthenes.

DRACO AND SOLON

102. Draco. — The eupatrids alone furnished the judges. Only they were supposed to know the laws according to which questions of right were decided and crimes punished. Now the commoners demanded that these laws should be written down, so that everyone could know them. Draco was appointed to do this. He could not alter them. It still happened that men who had received wounds in the wars for their country were led in chains to the market place to be sold as slaves. Little stone pillars marked almost every small farm as mortgaged for debt.

103. Solon. — The eupatrids finally, driven by fear of revolt, consented to have the laws changed. Solon, a eupatrid himself, but known for his fairness to the common people, was elected sole archon with the power to change the laws as he would see fit. Solon did not disappoint the confidence placed in him. He held his office for two years, 594 and 593 B.C., important years in the history of Athens.

104. THE LAWS OF SOLON. —

A. Economic Reforms: Several radical measures were calculated to sweep away the economic evils and prevent their return:

(а) The old tenants were given full ownership of the lands they had so far cultivated for the nobles;

(b) All debts were canceled, so as to give a new start;

(c) All Athenians sold into slavery and still in Attica were set free;

(d) Henceforth no Athenian could be sold into slavery;

(e) Henceforth no one was allowed to own more than a certain quantity of land.

B. Political Reforms:

(a) The economic reforms indirectly brought on political changes. Land, which was the sole basis of political power, could now be bought much more freely. Rich merchants, for instance, by buying land, could rise to the first class, while the nobles, who lost all the land so far worked by their tenants, might sink into the second or even third class. Thus the influence of the nobles in state affairs shifted considerably. Soon the name of eupatrids disappeared.

(b) Solon also made a number of direct political changes.

(1) He created a senate to prepare measures for the Assembly. The senators were chosen each year by lot, so that neither wealth nor birth could control the election.

(2) He greatly enlarged the Assembly by admitting the fourth class to the vote. He widened its power; it now not only voted on, but also discussed the proposals laid before it by the Senate; it elected the archons, and could try them for misgovernment.

(3) The Areopagus was made up of the ex-archons, and so was indirectly elected by the people. Its power was confined to the trial of murder cases, and to a general supervision of the morals of the citizens.

C. Additional Measures: Solon replaced the bloody code of Draco by a milder one; introduced coinage (§ 66); and limited the wealth that might be buried with the dead.

105. The Generation after Solon. — The Athenians were right in considering Solon one of their greatest statesmen. The keenness of mind required to see the roots of the existing evils; the boldness with which he conceived the right remedy; and the courage with which he formulated and enacted his thoroughgoing measures are worthy of the highest admiration. The clause which excluded the men of the fourth class from holding office will not surprise us, when we remember that the high state officers in those days drew no salaries.

After removing existing evils by drastic measures, even Solon could not prevent others from cropping up. The strife between the nobles and the people in the economic and political field was gone for good, but other parties arose, which fought for their class interests. They were especially “the Plain” (the rich land- owners) ; “the Shore” (merchants); “the Mountain” (shepherds and poor farmers). The disorders caused by these party quarrels were so great that twice within ten years no archons could be elected. This time a tyrant of the old stamp prevented a state of complete anarchy.

PISISTRATUS AND CLISTHENES

106. Pisistratus. — This man of noble descent rose twice against the nobility, and was twice defeated by them. The third time he kept himself in the saddle. He did not alter the constitution and laws of Solon. He merely took care that none but his friends were elected to the offices. He kept down disorder by means of his armed retainers. He led the life of an ordinary citizen without any pomp and display. The confiscated estates of banished nobles he divided among landless citizens. He beautified Athens; built an aqueduct to bring good water into the city; and drew around himself a brilliant circle of poets, sculptors, painters, and architects. To make rural life attractive, he set up religious festivals and courts of justice in the country. He died after a long reign in 527.

Pisistratus’ sons, who succeeded him, were by no means his equals. One of them, Hipparchus, was killed in a private quarrel, whereupon Hippias, the other, became a real tyrant in the worst sense. He was expelled in 510, and fled to the King of Persia.

107. Clisthenes, an exiled noble, now became the most prominent citizen. First, indeed, Athens had to defend itself against an attempt to bring back the tyrant. It forced an army sent by Sparta to withdraw, and also defeated the Thebans and Euboeans. It even captured the city of Chalcis on Euboea, introduced there a domocratic form of government, drove out thousands of nobles, and gave their land to four thousand landless Athenians. Contrary to the custom of the Greeks when founding colonies, these men remained citizens of Athens under the name of cleruchs. It was a new way of colonization and afforded a means to care for poor citizens without losing their interest and active assistance.

Meanwhile, however, Athens had still some serious problems to solve. The old rivalry between the Shore, the Plain, and the Mountain still caused great friction. There was besides a large class of aliens, that is, foreigners who had immigrated into Attica on account of business, and many of whom had become very rich. According to Greek views, they were not citizens, nor could their children or children’s children become citizens. Yet they would have made an excellent addition to the power of the state.

108. How Clisthenes Reformed the Constitution. —

(1) Clisthenes divided the whole of Attica into a hundred regions, called demes. The citizens then living in any one of these geographical sections were entered into a special roll, as a recognition of their rights of citizenship. The hundred demes were grouped into ten tribes. The demes of the Shore or the Plain or the Mountain were promiscuously ascribed to the tribes, so that each tribe contained demes of each of the three classes. As a result, each tribe consisted of ten separate patches of land, situated perhaps miles apart. The old three divisions of the land, Shore, Plain, Mountain, were therefore broken up and their party strife was impossible.

(2) He used this opportunity to enroll into the list of each deme all the aliens that actually lived in it, thus ending a situation which might have grown into a danger of the state. (Aliens arriving after this did not become citizens.)

(3) Clisthenes furthermore greatly increased the power of the Assembly of the People. It was no longer necessary that the Senate, now known as the Council of Five Hundred, pass on a measure before it be put before the Assembly. The Assembly settled all matters of taxation, dealt with foreign powers, and gave directions to the commanders of army and navy. The power of the archons, too, was greatly curtailed; ten generals, elected yearly by the Assembly, took over most of their duties. The real head of the Athenian state was the Assembly of the People. It attended to nearly all the functions which our Constitution assigns to Congress and President together.

(4) Another very peculiar measure brought about by Clisthenes is to be mentioned: ostracism, a device to prevent the rising of another tyrant or of any influential man who might cause civil strife. Once a year the Assembly was asked to vote against any man whom it considered too powerful. (Potsherds, ostraca, and similar things served as ballots.) If at least 6000 votes were cast, the one who had the largest number against him was obliged to leave the city for ten years, but without any prejudice to his property or civic rights. While it may have served a good purpose in the beginning, ostracism later on often was abused by ambitious politicians to get rid of their opponents.

109. Neither the Greeks nor the Romans invented the system of representation. The Assembly was not a gathering of men elected by the citizens and representing them, as our congressmen and senators represent us, but a meeting of the citizens themselves. Only the Council of Five Hundred was a sort of representatives. In Sparta, too, the Assembly consisted of the Spartans themselves, though their elected little senate of thirty had considerable power.

ARTS AND SCIENCES

110. Architecture, sculpture, and painting were well on their way to the brilliancy they were to manifest in the next age.

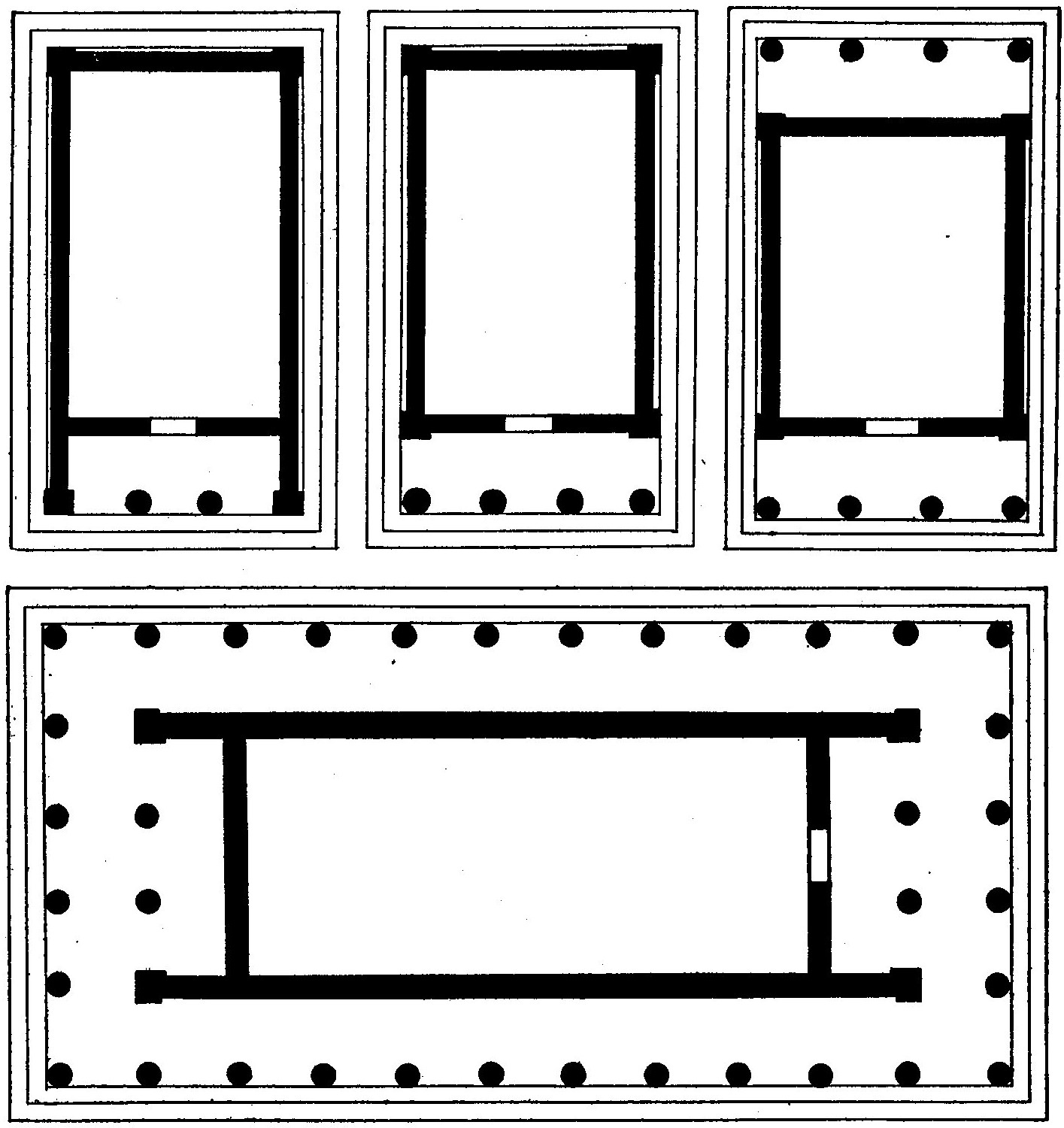

The variety is much greater than can be shown here. The lower is the ground plan of the so-called Temple of Theseus at Athens.

Architecture in particular showed the lines by which Greek buildings were to be marked for all times to come. The most beautiful and most prominent structures, however, were the temples, in the erection of which every city took its greatest pride. At a later date, the theater also became conspicuous.

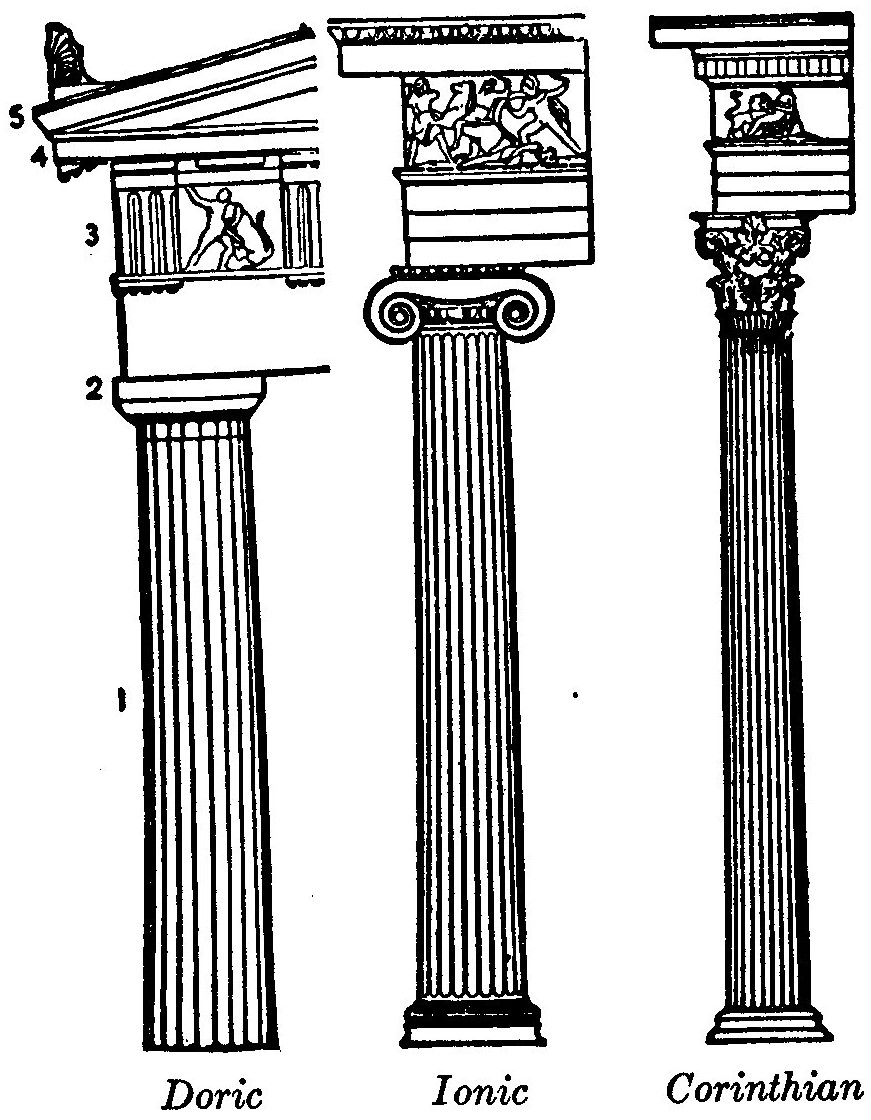

GREEK COLUMNS

1, shaft; 2, capital; 3,frieze; 4, cornice;

5, part of roof, showing low slope.

The walls of a Greek temple enclosed one room, commonly rather small, for the statue of the god or goddess. Usually another still smaller compartment served for the safe-keeping of the offerings. Only the priests entered the temple; the people when praying stood in front of it. The temple commonly had columns, either in front, or in front and rear, or Corinthian surrounding the walls on all sides. The roof projected beyond the walls, so as to extend over the columns also. According to the character of the columns, the Greeks distinguished the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian “orders.” In the Doric order the column has no base of its own, but rests directly upon the foundation from which the walls rise. The shaft is grooved lengthwise with some twenty flutings. The capital is severely simple, consisting of a circular band of stone, capped by a square block, without ornament. Upon the capitals rests a plain band of massive stones (the architrave), and above this is the frieze, which supports the roof. The frieze is divided at equal spaces by triglyphs, a series of three flutings; and the spaces between the triglyphs are filled with sculpture. The Doric style is the simplest of the three orders. It is almost austere in its plainness, giving a sense of self-controlled power and repose. (See page 125.)

The Ionic order came into general use later. In this style, the column has a base arranged in three expanding circles. The shaft is more slender than the Doric. The capital is often nobly carved, and it is surmounted by two spiral rolls. The frieze has no triglyphs: the sculpture upon it is one continuous band.

The Corinthian order is a later development and does not belong to the period we are now considering. It resembles the Ionic; but the capital is taller, lacks the spirals, and is more highly ornamented, with forms of leaves or animals. (See illustration on opposite page.)

Let the student realize the difference between the temples of the Orientals, especially the Egyptians, and those of the Hellenes. The Oriental temple, massive, majestic, awe-inspiring, magnificent, has a certain gloominess. This latter quality is totally absent in the Greek temple. The colonnades which hide the walls, the flutings of the columns, the capitals and friezes, the many sculptured representations, produce a pleasing variety of appearance.

111. Poetry. — During the earliest part of our period Homer was the poet. He had many imitators, more or less skillful, who produced epics, i.e., narrative poems, of the style of the Iliad and the Odyssey. But Homer’s works continued to be read, memorized, studied, declaimed, and sung, during the whole of Greek history. The great variety of subjects treated in them with consummate elegance was bound to give this practice an ennobling influence and produce great refinement in literary art. While Homer always remained in vogue, the seventh and sixth centuries also saw the beginning of lyric poetry, which describes feelings rather than events. Two women, Sappho of Lesbos, and Corinna of Boeotia, are especially famous. Pindar of Thebes glorified the Olympic games. Simonides and Tyrtaeus wrote odes to arouse patriotism. The purpose of the works of Hesiod is to impart useful knowledge in poetical form, and to acquaint the Greeks with the fabulous origin and genealogy of their gods. (One of his books may be styled a “Textbook on Farming” in the garb of poetry.)

112. Philosophy. — At this time Greeks began to think about the nature of things and their origin. Thales of Miletus taught that all things come from water. Heraclitus of Ephesus believed that “ceaseless change” is the very nature of everything. The great Pythagoras, the founder of the school of the Pythagoreans, directed philosophy to the regulation of man’s conduct. These men looked upon mathematics, physics, and astronomy as branches of philosophy. They predicted eclipses of sun and moon with tolerable accuracy. Of course they knew that the earth is a globe. To Pythagoras is ascribed the famous demonstration about the square on the hypotenuse of a right triangle.

Summary. — We have now reached the threshold of a new and most eventful period. The Greeks were a people vastly different from those we learned to know in the Orient. In the Orient we met with governments controlled by the most absolute monarchs. In Greece we find the cities tending toward democratic constitutions. Oriental culture is more or less strange to us. With Greek literature and with Greek architecture we feel at home.

We shall now see the contest between the Orient and Europe. Europe’s champions were the Greeks. They were prepared for the struggle. They had developed a new fighting machine, the heavy-armed infantry, and they possessed in Sparta a military leader of great power and ability.

From now on, too, the details of Greek history are much better known and a more connected story is possible.