The following is an excerpt (pages 118-136) from Ancient and Medieval History (1946) by Francis S. Betten, S.J. Although some information may be outdated, the Catholic historical perspective it provides remains pertinent. Use the link at the bottom of post to read the previous/following pages. Use the Search box above to find specific topics or browse using the Resources tab above.

CHAPTER XIII

THE ATHENIAN EMPIRE AND ITS CAPITAL IN PEACE

THE GOVERNMENT

140. Population and Revenue of the State. — The Athenian Empire probably counted some three million people. Attica itself had 300,000, nearly half of whom were slaves. Some 35,000 citizens were able to bear arms. There were, besides, the cleruchs (§ 107), that is, citizens with full rights who had been settled outside of Attica. Though these numbers are small if compared with the seventy or more millions of the Persian Empire, we have seen what they meant in a contest of arms. The Athenian Empire probably was the mightiest state of its time.

From mines and other state property, from harbor dues and taxes of the subject cities the empire drew about a million dollars. Athens treated all this money as her own and used it also for the beautification of the capital. She fulfilled, however, all her duties faithfully. The cities could not even have kept down piracy for the money they paid to Athens. The taxes of the Asiatic cities were only one sixth of what they had been paying to the Persians.

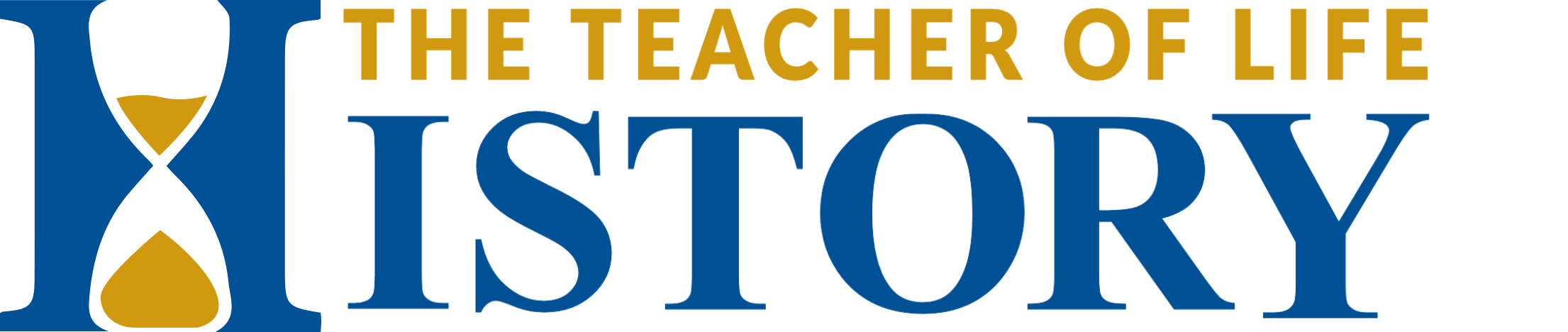

This shows some structures of the Roman period. The term “stoa,” which appears so often in this map, means “porch” or portico. These porticoes were inclosed by columns, and their fronts along the Agora formed a succession of colonnades. Only a few of the famous buildings can be shown in a map like this. The Agora was the great public square, or open market place, surrounded by shops and porticoes. It was the busiest spot in Athens, the center of the commercial and social life of the city, where men met their friends for business or for pleasure.

141. Archons and Generals. — After the abolition of royalty, ten archons acted as supreme magistrates. Their power was limited under Clisthenes by the introduction of the office of the ten generals (§ 108, 3). Gradually, more by custom than bylaws, the powers of the generals increased greatly at the expense of the archons. The cause of this change was the fact that Athens was obliged to keep up a considerable fleet and to be ready for all kinds of warlike operations if she meant to fulfill her duties as head of her empire. The generals were commanders in chief of the contingents of the ten tribes. They controlled the administration of army and navy, appointed the captains, conducted the levy of the soldiers, had charge of the depots of ammunition and weapons, collected the property tax, and took a prominent part in the negotiations with foreign powers. In the Assembly they might at any moment introduce proposals, which had to be taken up immediately. They could even summon extraordinary sessions of the Assembly. The archons had little left beyond honorary duties connected with religion. Even the war-archon had lost all power in military affairs. The first archon, however, always enjoyed the distinction that the year was named after him.

142. The Council of Five Hundred originally prepared all measures which were to come before the Assembly. By the time we speak of, any citizen present at the Assembly might propose new matter, and if the Assembly approved of its being taken up, it was referred to the Council to report on at the next session. Our United States Senate has a special committee for financial laws, another one for foreign relations, another one for matters of war. All these functions were combined in the Council of Five Hundred. The Council, moreover, and this was one of its heaviest duties, kept strict supervision over the expenditures, examined bills and receipts, and saw that all moneys were expended according to law. To be a councilor was no sinecure. The councilors were appointed by lot from the candidates whom each of the hundred demes (§ 108) had proposed.

143. The Assembly. — This consisted of all male citizens who cared to be personally present (§ 108, 3). The Assembly was really the head of the state. All magistrates were responsible to it, and it could at any time depose them, or bring them to trial, or interfere with the conduct of any business. Special officials summoned it forty times a year for regular meetings, and for extraordinary meetings as often as they were required. They also published, five days before every regular meeting, a program of the business to be transacted. But the Assembly was not bound to adhere to it. Several times a year a vote was taken to decide whether the officials were carrying on their business correctly. Though the decrees of the Assembly were to conform to the existing laws, any law could be attacked by a citizen, and if the Assembly approved of the reasons against it, the matter was referred to a board of a thousand “lawgivers,” who were at liberty by their final vote either to uphold the old law, or to modify it, or to substitute a new one.

144. The Law Courts. — In the Athenian law courts there was no difference between judges and jurymen. The jurymen not only decided the question whether or not the man was guilty; they also determined the penalty. Every year six thousand jurors were appointed by lot from those who offered themselves for the service (mostly older men past the age of hard work). A thousand were held in reserve. Each of the ten Athenian law courts consisted of five hundred jurors with a president. They decided criminal cases, civil cases (i.e., such as refer to property), and political disputes. (Cases of murder were tried by the Areopagus, § 104.) The decision was given by secret ballot, and there was no appeal to any higher court.

146. Leaders of the People. — The people gathered in the Assembly would naturally look for guidance. They had their chosen magistrates, and certainly gave them their confidence. But as a matter of fact, there was commonly some prominent citizen on whom they principally relied, a man who enjoyed the reputation of unselfishness and ability. Such men could exercise an influence much greater than many officials. They could sway the Assembly as they wished. They were popularly styled demagogues, “leaders of the people.”

Pericles, mentioned several times, was the demagogue of his time. For a quarter of a century he ruled the commonwealth of Athens almost as absolutely as any tyrant had ever done. Though he was often elected general, he owed his power to his personal ability alone. With rare insight he perceived what enterprises would promote the greatness and glory of Athens; and with an eloquence, equally rare, he always knew how to make even hard things acceptable to the people. He had antagonists, who opposed the measures suggested by him. But he always carried the Assembly with him by the force of his reasoning, or, sometimes, by the thunder of his voice. Under his direction Athens became a mighty and magnificent city. Those who after his death tried to step into his shoes were not his equals.

146. Political Training. — Some 20,000 men, more than half of the body of male citizens, were constantly in the pay of the commonwealth, either as soldiers or as civil officers. Among the latter were the 6000 jurymen, the five hundred councilmen, then the army of city officials, harbor masters, officials of the treasury department, collectors of taxes and harbor dues, both in Athens and throughout the empire. The salaries of these men were not large. The pay of the jurymen for a session just sufficed to support a frugal man for one day. The highest offices were not salaried at all. It was the duty towards the state that kept these men at their tasks. This naturally generated a high degree of public-spiritedness, a dominating desire for the city’s greatness, a kind of forgetfulness of self. (We do not read of defraudations of public moneys, though they probably happened, partly because there was too much inspection and examining and auditing and counter-inspection of all those offices where money was handled.) We may not like the idea that the assembly of the common people decided the most weighty matters. But unquestionably “the Athenian, by constantly hearing questions of foreign policy and domestic administration argued by the greatest orators the world ever saw, received a political training which nothing else in the history of mankind has been found to equal.” “The Assembly was an assembly of citizens, of average citizens without sifting or selection; but it was an assembly of citizens among whom the average stood higher than it ever did in any other state.”

ATHENS AS THE PRINCIPAL HOME OF GREEK CIVILIZATION

Greek civilization, more or less uniform all through Hellas, had nowhere reached so high a degree as it did at Athens during Pericles’ administration and greatly through his encouragement and support. Its perfection can nowhere be better realized than in the culture of that imperial city.

147. Architecture and Sculpture. — Athens became the most beautiful city of the world, so that ever since her mere ruins have enthralled the admiration of men. Under the charge of the greatest artists arose temples, colonnades, porticoes, inimitable to this day.

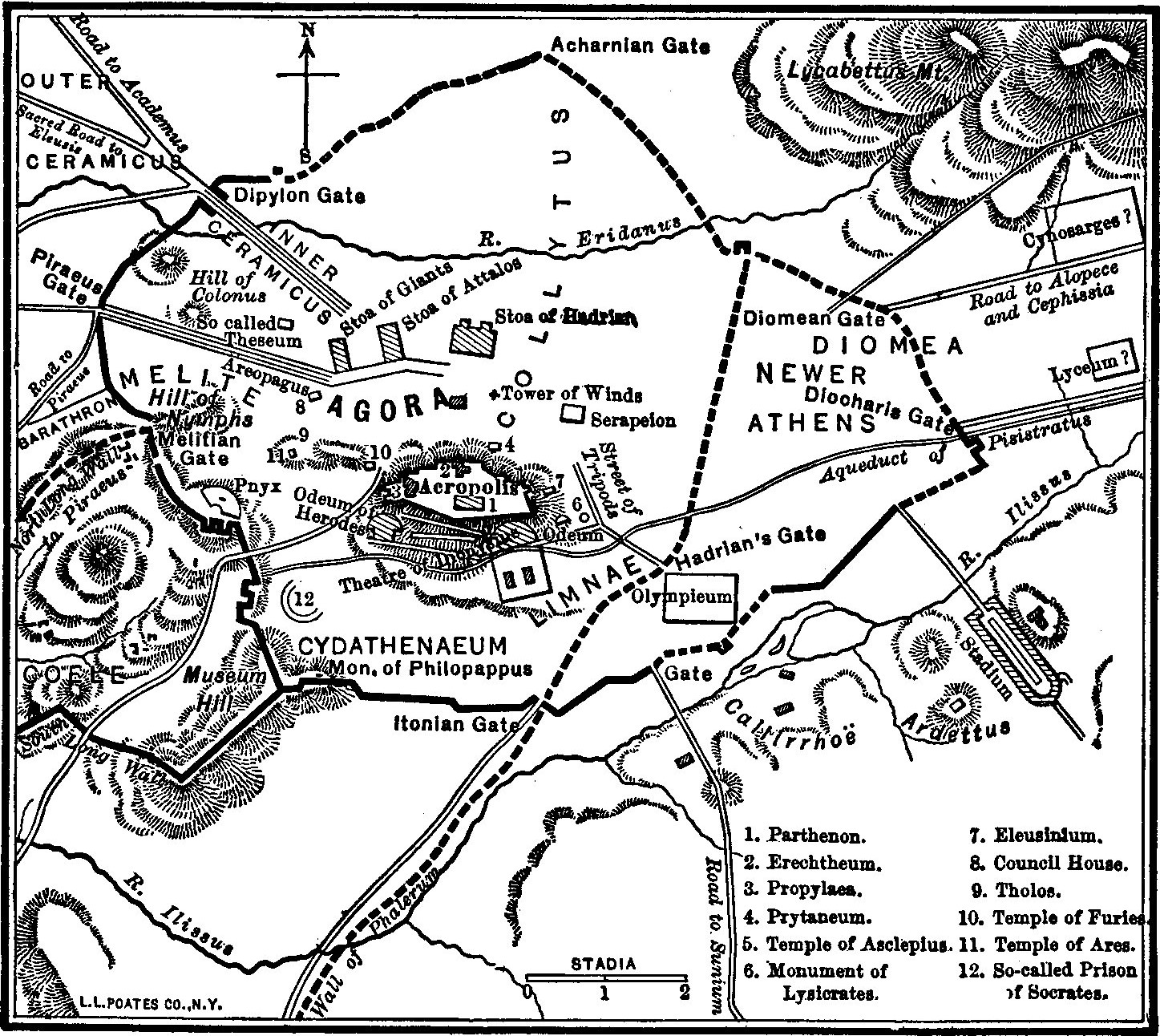

The center of architectural splendor was the Acropolis, formerly a strong fortress upon a steep hill. It was now exclusively devoted to religion and art. A stately stairway of sixty marble

steps led to a series of colonnades and porticoes (the Propylaea) from which the visitor emerged upon the leveled top of the hill, to find himself surrounded by temples and statues, any one of which might make the fame of the proudest modern city. The eyes were attracted above all by the Parthenon (Maiden’s Chamber), the temple of the virgin goddess Athene. It remains absolutely peerless in its majesty and loveliness among the buildings of the world. It was built in the Doric style, not very large, some 250 feet by 100. The effect was due not to the sublimity

and grandeur of vast masses, but to the perfection of proportion, to exquisite beauty of line, and to the delicacy and profusion of ornament. Fifty large statues adorned the pediment (see illustration, page 125), and nearly 500 different figures were carved upon the frieze. Many of the sculptures were the work of Phidias, who besides produced a gigantic bronze statue of Athene, which stood upon the Acropolis, and a much more beautiful one of gold and ivory inside the Parthenon.

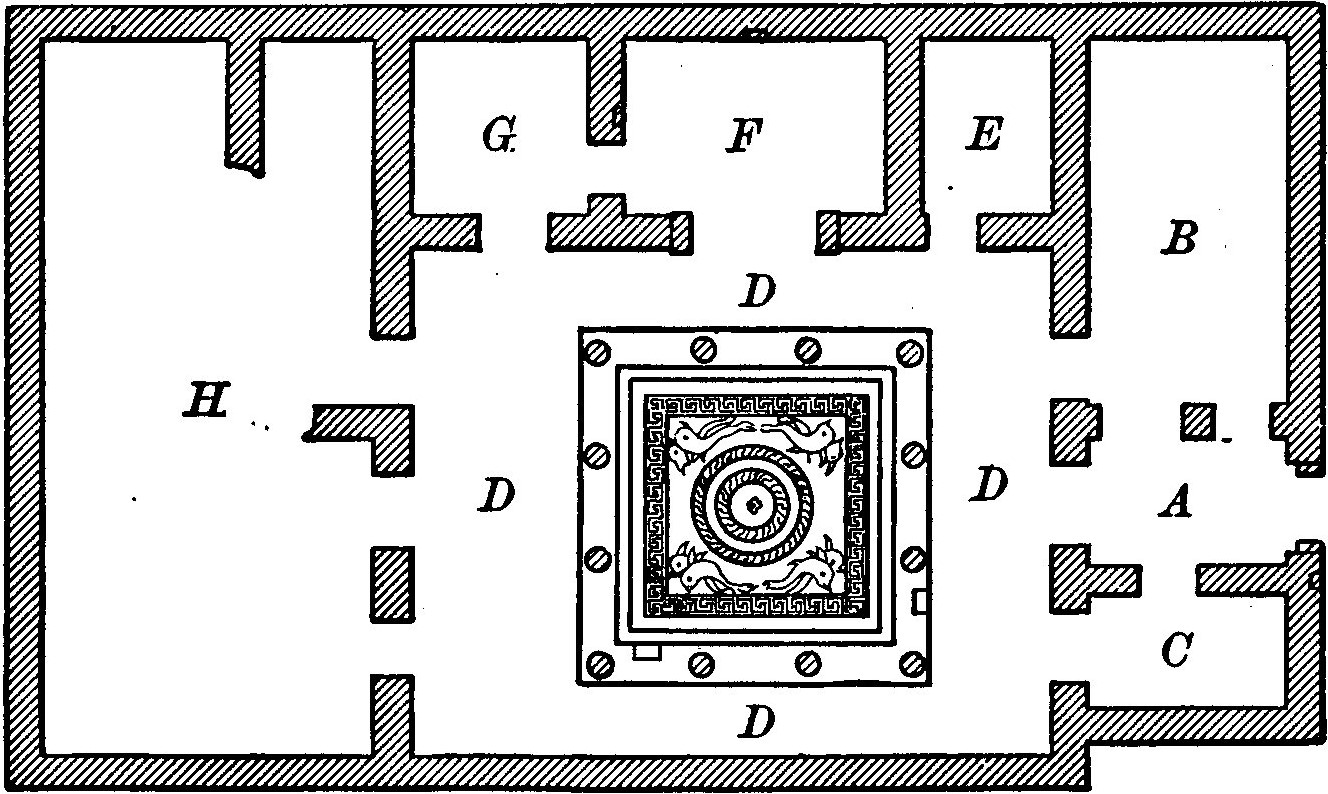

To the right, foundations of the stage building. The circle in front of it was a sort of subordinate stage for the chorus, which by songs, dances, and processions supported the action of the play.

148. The Drama and the Theater. — As the tenth century was the epic age of Hellas, and the seventh and sixth centuries the lyric (§ 111), so with the fifth century begins the dramatic age. The great literary productions of this time are tragedies, that is, plays of a solemn and serious character, and teaching some high moral doctrine. The most famous tragic poets are Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, all of Athens. Their tragedies, of which only thirty-one survive, are all high-class plays, though very simple in their external make-up. Comedies, too, came into vogue, the sole purpose of which was to amuse and entertain. The Greek comedy frequently was of a low and coarse character, and was abused for political purposes; for instance, to ridicule men like Pericles or Socrates. The comedies were given between the acts of the tragedies as a sort of relaxation. The Greeks were very fond of their classic tragedies. Pericles made it possible for every citizen to have free access to these noble performances.

Every Greek city had its theater. A theater consisted of rows of seats, rising in tiers in a semicircular shape, commonly cut into the rock of a hillside — and a building of moderate size with the open stage standing in front of the seats. (See the pictures on page 126.)

Every Greek city had its theater. A theater consisted of rows of seats, rising in tiers in a semicircular shape, commonly cut into the rock of a hillside — and a building of moderate size with the open stage standing in front of the seats. (See the pictures on page 126.)

149. Oratory was practiced and studied in all Greek cities, but in none more zealously than in Athens. It was needed in the courts and in the political meetings. Unfortunately, the great Pericles did not preserve his orations, which so often held the vast gathering spellbound. But we have still many of the speeches of Demosthenes, of the next century, which excel in the arrangement of the matter and the polished beauty of language. Demosthenes is considered the greatest orator of the world. He was the model of Cicero, the famous Roman. The orations of both are still studied in our schools.

150. History. — At this time lived the father of Greek history-writing, Herodotus, born at Halicarnassus in Asia Minor, and a personal friend of Pericles. Among other works he wrote a history of the Persian Wars. Thucydides, an Athenian, the historian of the Peloponnesian War, is the first “scientific” historian.

151. Philosophy, too, saw a rapid development during the age of Pericles, and Athens was its most important home. Anaxagoras of Ionia, a friend of Pericles, taught that the ruling principle in the universe was Mind: “In the beginning all things were chaos; then came Intelligence and set all in order.” Others tried to answer the question, “How does man know about the universe ?” Since their explanations were not very satisfactory, the class of the Sophists came up. They said that we can know nothing and must be satisfied with appearances. The Sophists also taught the art of oratory, and were the first to demand pay for their instruction. They were accused of teaching youth “how to make the worse appear the better reason,” and the name “sophists” received an evil significance. But many Sophists were really good thinkers.

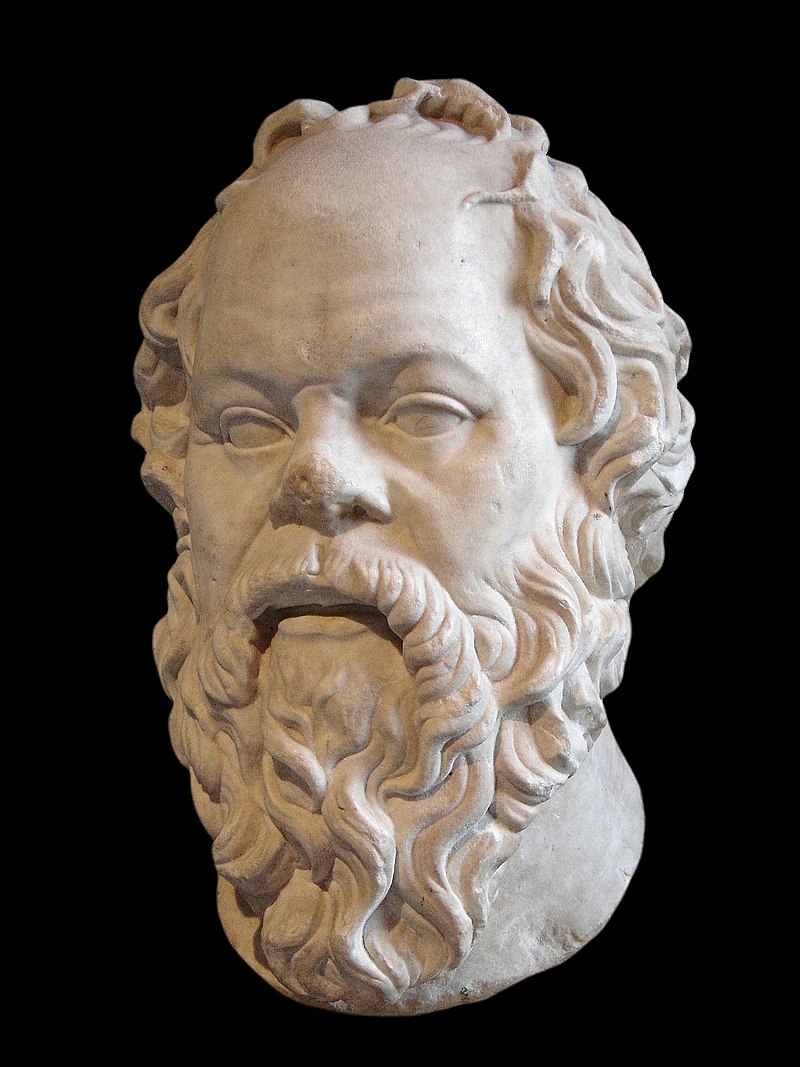

152. Socrates. — Few Greeks had so wholesome and lasting an influence on their fellow men as did Socrates, who blazed the way for a new and important school of philosophy. He made it his vocation to gather around him young men, and instruct them how to lead good moral lives. Unlike other philosophers he accepted nothing for his teaching, though only great frugality enabled him to live on the revenue of his little sculpture shop without working himself. His numerous antagonists, chiefly the Sophists, he put to shame by asking them innocent-looking questions, and showing how foolish their answers were, much to the merriment of his numerous friends. He discoursed preferably on the problem how one must live in order to be a truly good man. By independent thinking he moreover convinced himself that man’s soul is vastly different from his body; that it cannot die, that there must be a life of bliss after death for those who lead a good life. He also approached very closely to the belief in one God. His way of teaching, the “Socratic method,” consisted in proposing questions to his disciples, and in leading them with sympathetic kindness to see, or rather to find out for themselves, the truth he wished to bring home to them. Socrates left no writings. What we know of him we owe to his devoted friends and disciples, especially Xenophon and Plato. The latter became one of the greatest philosophers of the world. Plato’s immortal philosophy (§ 188) grew out of the doctrines of his teacher Socrates.

Socrates had many enemies who could not brook his stern preaching of morality. They finally trumped up a charge against him. One of the Athenian Courts of Five Hundred condemned him to drink the poison cup. When asked by his followers how they should bury him, he replied, “Bury ME? you mean to say, bury my body; my body is not I. You will not succeed in burying ME.”

Summary. — The amazing extent and intensity of Athenian culture overpower imagination. Artists, philosophers, and writers swarmed to Athens. The names that have been mentioned give only a faint impression of the splendid throngs of brilliant poets, artists, philosophers, and orators who met each other in the public halls, the houses of the great, and in every street. “Never before or since,” says a modern critic, “has life so richly developed as it developed in the beautiful city which lay at the feet of the virgin goddess.”

163. Limitations. — This brilliant life of Hellenic culture had its limitations.

(a) It rested on slavery. As already stated, half the population consisted of slaves, who performed the more menial labor in city and country, while the citizens lived for politics and, if necessary, warfare. Nobody thought of educating them. They were white people, many of them Greeks. On the whole they were not treated very harshly, though those laboring in the public mines succumbed in large numbers to the hardships.

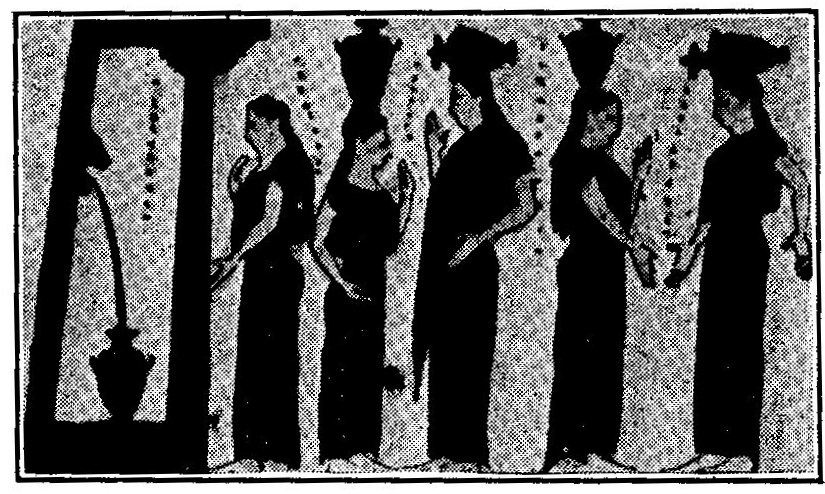

(b) Greek culture was for men only. Very little education was given to girls. The women of the better classes were rarely seen on the street. They never met other men than their relatives. The lower classes were forced by circumstances to permit their women a larger amount of freedom. (See picture on page 131.)

(c) Culture did not extend to moral conduct. Religion merely demanded that religious festivals, processions, sacrifices, etc., be kept regularly, and this was done at Athens with a quite uncommon splendor. Moral ideas are to be sought in the works of poets (dramatists, for instance) and philosophers. The Greeks accepted a rather unlimited search for pleasures as unobjectionable. Self-sacrifice had little place in their moral code. They lacked altogether the Jewish and Christian sense of sin. Their chief motive for right conduct, as far as it went, was a certain natural respect for moderation. Individual characters at once lofty and lovable were not numerous. In beautiful Hellas, in the most cultured population, grew up that moral degradation which in due time was to spread along the shores of the Mediterranean.

(d) Greek science did not try to find out the truths of nature by experiment. The ancients had chiefly such knowledge of the world about them as they had chanced Upon. Nor did they add anything to what knowledge of nature men possessed before them. This is one of the causes of the incredible simplicity of their lives. Even the best houses were without plumbing or drains of any sort, the clothes without buttons or even hook and eye. This fact, however, is rather instructive than bewildering. There is a higher civilization, more essential than material achievements. (See IT. T. F., “Civilization.”) The average Athenian no doubt excelled the average man of our times in brain power, and the Greek mind performed wonders in literature and art and philosophy.

The lack of control over nature, however, had another serious drawback. Without our modern inventions and machinery, it has never been possible for man to produce wealth fast enough so that many could take sufficient leisure for a more refined living. Even with us too much wealth remains in the hands of a proportionately small number of the very rich. With the Greeks it was still less possible to give to many an ample share. There was too little to go around.

EVERYDAY LIFE IN THE AGE OF PERICLES

154. The houses were very simple in comparison with ours. A man thought his house of little account. It was merely a place to keep his women folk and little children and his movable property, and to eat and sleep in. His real life was spent outside. The poor man’s house was a one-story mud hut with one or two, or perhaps three rooms. Even a “well-to-do” house was merely a wooden frame covered with sun-dried clay. Houses were built flush with the street, and on a level with it — without even a sidewalk or steps between. The door, too, usually opened out, so that passers-by were liable to bumps, unless they kept well in the middle of the narrow street.

The principal room was a square court open to the sky, but partly covered on one or several or all four sides by a roof supported by columns. From this court several doors opened into the dining room with a kitchen, and into other rooms used for storage or sleeping. This was the men’s section. If the owner could afford it, there was another section arranged in a similar fashion for the women. This, however, often formed a second story. Sometimes the house had a small garden in the rear. The few windows were filled with a close wooden lattice.

155. Streets. — Splendid as were the public portions of Athens, the residence streets were narrow and irregular, hardly more than crooked dark alleys. They had no pavement, and they were littered with all the filth and refuse from the houses. It was in later times that the wealthy built more comfortably on the hills near the city.

156. The Family. — Greek laws recognized only “monogamous” marriages, though this does not mean that they came up in any way to the perfection of Christian matrimony. We no longer find lovely pictures of family life as in former times. To the age of seven, boys and girls lived together in the women’s apartment. Then the boy began his school life and received his intellectual and military training. The girl was instructed in the household duties, and if the family could afford it she spent a great deal of her time at music and play. She did not leave the house except on some festival occasion, when she walked with the maidens of the city in religious processions. Practically, her childhood lasted until she married. She was not asked in the choice of her partner for life. The parents settled this matter for her. Law and public opinion allowed a father to expose a newborn child to die. Divorce was lawful, and the husband easily found a sufficient plea for it.

157. Dress. — The pictures and sculptures represent women dressed in flowing garments, fastened at the shoulder with clasp- pins and gathered in graceful folds at the waist. The chief article of men’s dress was a shirt of linen or wool, which fell about to the knees, and was often clasped with a girdle. Over this they threw a long mantle falling in folds to the feet. (See picture on page 127.) They commonly wore sandals, though there was a great variety of footgear.

158. Occupations. — Most of the hand labor consisted of tilling the soil. The Greek farmer manured his field skillfully, but otherwise he made no advance over the Egyptian peasant. Some districts, like Attica and Corinth, did not furnish food enough for their population. They imported grain from other parts of Hellas, from Thrace, or from Egypt. They could do so, because they also exported their own manufactures. In Pericles’ time appeared factories, that is, places where certain articles were manufactured in large quantities. As there were no machines, this could be done only by multiplying the workers, who were commonly slaves. Commerce required much labor, too, for the building and loading and unloading of the ships. Trades and handicrafts were very numerous. There were smiths and carpenters, dyers, goldsmiths, ivory workers, painters, embroiderers, turners, wagoners, rope- makers, flaxworkers, tanners, shoemakers, and miners, and these men commonly took a noble pride in their work. Many of them were in the pay of the artist who produced those admirable buildings and other works of art. Their pay was usually very small, but a Greek needed little to live.

159. The men of leisure looked with disdain upon the working classes. Slave labor had degraded labor in general. The ideal of the Greek gentleman was to have his revenue without being obliged to work for it. After his very frugal breakfast, he would leave his house to find his friends and to walk with them in the shaded arcades of the market place and discuss matters of business or politics. About noon he would return home for a light lunch, and perhaps take a short rest; or he would prepare the speech he wished to deliver at the next Assembly. If he were interested in literature or philosophy, he would take to his rolls of papyrus. He would not omit the daily bath, either at home or in some public bathing house, where at the same time he held conversation with acquaintances. He took his principal meal in the evening, rarely, however, with his family. As a rule he had invited guests or was himself the guest of a friend. With playful talk, story-telling, singing, and other kinds of merrymaking the time passed often until late in the night. His life was more strenuous during the several years in which he held state offices. At other times, too, the Assembly, theater, and religious festivals encroached considerably upon his leisure time. (For a description of an Athenian banquet see Davis’s A Day in Old Athens, pages 181 ff.)

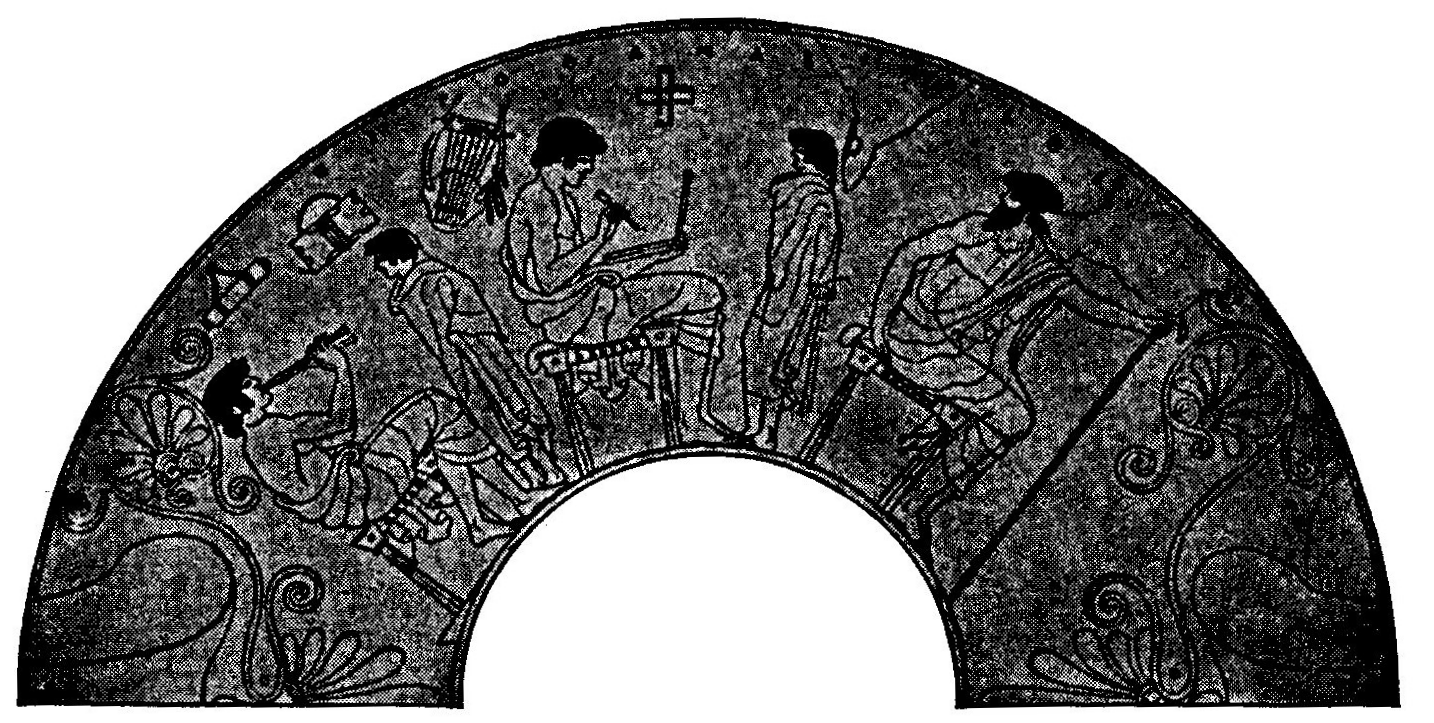

SCHOOL SCENE

(From a bowl painting.) One teacher is showing how to use the flute. Another is correcting a boy’s exercise. The seated bearded man is a “pedagogue.”

160. Education. — The rich man’s boy went to school, accompanied by a “pedagogue.” (This word means “boy-leader”; its use for “teacher” is of later date.) He wrote his elementary exercises on tablets coated with wax. The chief subjects were the reading of Homer and music. Homer was to the Greek at once Bible, Shakespeare, and Robinson Crusoe. The study of other great poets and dramatists came later. The witnessing of the best theatrical plays and the constant sight of the noblest edifices could not but contribute to develop his taste in the most favorable manner. Regular athletic exercises also began rather early. Though they were indulged in very freely, deliberate care was taken not to have them interfere with the youth’s more important mental development. When about eighteen, the youth devoted two years exclusively to certain military functions, and thus prepared himself more directly for active service in the army. The whole education was calculated to produce perfect gentlemen, with a taste for everything beautiful and worth the admiration of man, and at the same time to make him a valuable warrior for the service of his beloved city.