The following is an excerpt (pages 186-195) from Ancient and Medieval History (1946) by Francis S. Betten, S.J. Although some information may be outdated, the Catholic historical perspective it provides remains pertinent. Use the link at the bottom of post to read the previous/following pages. Use the Search box above to find specific topics or browse using the Resources tab above.

CHAPTER XIX

CONQUEST OF THE WESTERN MEDITERRANEAN

ROME AND CARTHAGE COMPARED

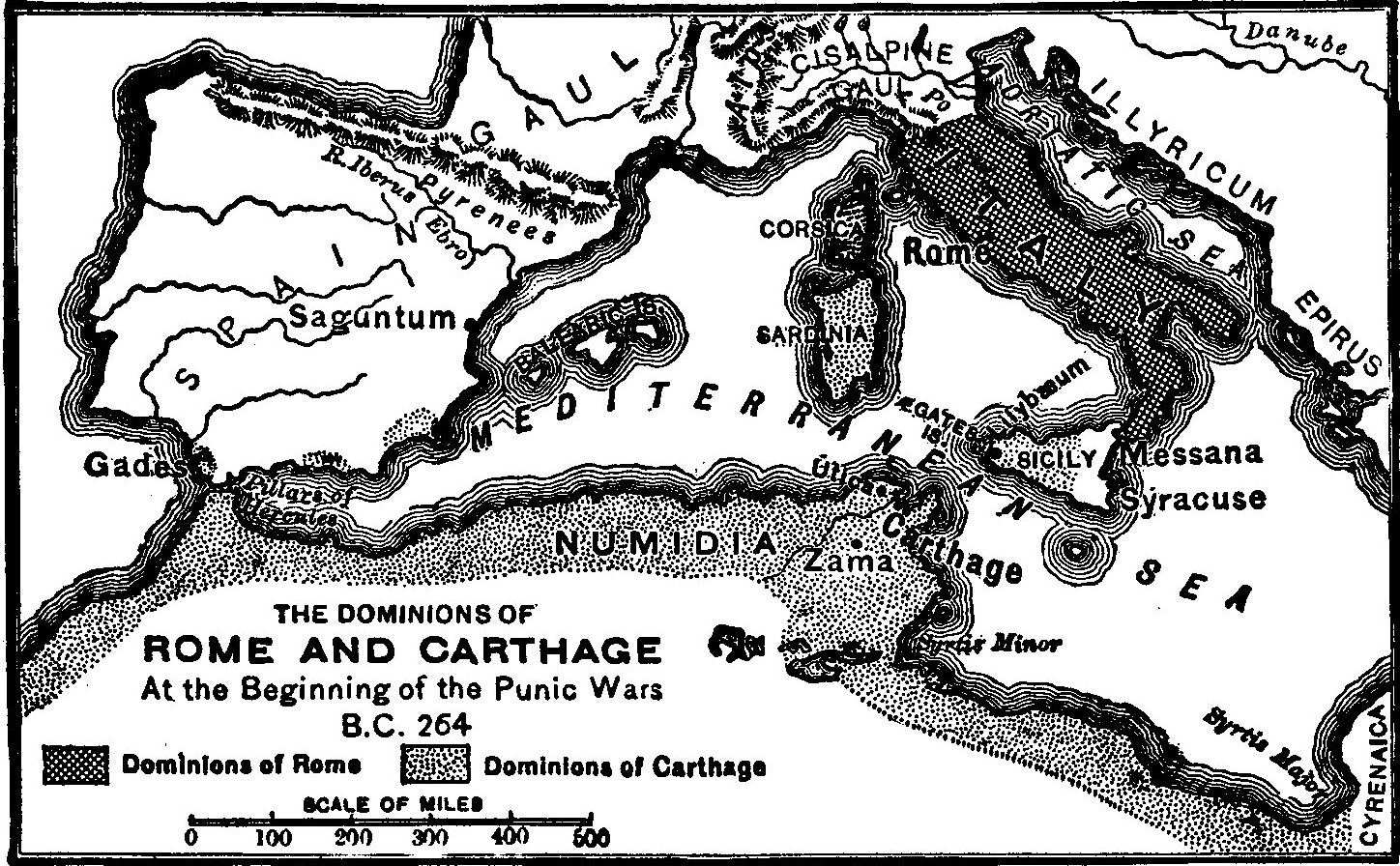

By the conquest of Italy, Rome had become a new great power on the Mediterranean. On the shores of that midland ocean there extended in the east the kingdoms of Egypt, Syria, and Macedonia, the heirs of the empire of Alexander the Great (see § 183). In the west there were now two states, both of them republics, Rome and Carthage. Carthage, the ancient foundation of the Phoenicians (§ 53), had on the whole successfully withstood the encroachment of the Hellenic cities in Sicily. But now the boundaries of Rome were several hundred miles nearer to those of the Carthaginian possessions, though still separated by the districts of some Greek towns. Since both parties were bent on extending their dominions, it was evident that a bloody conflict was to come. Like that of the Greeks against the Persians, it was to be a war between Europe and Asia, Asia being represented by the great Phoenician colony situated on the opposite shore of Africa.

231. Carthaginian Culture. — Being in constant touch with the highly developed civilization of the Orient, the Carthaginians possessed everything that made for material refinement, though their own artists and craftsmen were imitators rather than originators. Of their poetry, philosophy, science, etc., we have no records, probably because of the thorough destruction of the city by the Romans. Their religion, however, was the gloomy worship of the old Phoenician gods, attended by great lasciviousness and numerous human sacrifices (§ 54).

232. The Resources of the Two Powers. — Rome was at the head of a well-knit state, with most of its men having a direct interest in the common cause as citizens, and the rest tied to them by bonds of loyalty and the hope of reward. None of them had anything to gain if Rome was defeated, but much to hope for if Rome was victorious. Rome had an excellent army. Her greatest weakness was the lack of a navy. In Carthage a limited number of very rich people held all the political power. The subject cities and regions were either loaded down with heavy tribute or practically treated as slaves. None of them had any interest in the victory of the ruling merchants of the capital. Her armies consisted entirely of mercenaries. One of her troubles was the spirit of mutiny among soldiers. Her navy, however, was the first in the world. It made her a formidable opponent wherever ships could be of service.

233. The real cause of the wars between Rome and Carthage was the mutual jealousy of the two states. Carthage not without reason considered the enormous increase in Roman power resulting from the Italian wars as a threat to herself. She did not think Rome would stop at the shores of Italy. Rome, on the other hand, noticed with alarm how her rival gained ground in Sicily, and feared that, with this large island under her control, Carthage would not hesitate to cross the narrow strait between Sicily and the Italian peninsula. The three wars which resulted are known as the Punic Wars, Punic being another word for Phoenician.

THE FIRST PUNIC WAR, 264-241 B.C.

234. Occasion. — A band of mercenaries, who had been dismissed by the tyrant of Syracuse, instead of marching home, took possession of the city of Messana, and from this stronghold harassed the whole northeast corner of Sicily for many years. The tyrant of Syracuse, “King” Hiero, undertook a war against them. One party of them appealed to Rome, the other to Carthage for aid. Rome decided to aid the mercenaries who had appealed to her. In 264 her legions for the first time crossed the sea. They found the Carthaginians already in possession of Messana. The First Punic War had begun.

235. The War. — For many years Rome could make no headway, because Carthage was the undisputed mistress of the sea. She reinforced her troops on the island at pleasure, and made good the threat that without her consent no Roman soldier would wash his hands in the sea. But the Romans, too, built a fleet, and successfully met the Queen of the Seas in her own element. They had fitted out their galleys with bridges, some five or six feet wide, which before the battle were raised on one end. When a Roman ship came near enough to a Carthaginian, they let the bridge fall upon the latter, and an iron hook would engage and hold it. The Roman soldiers could rush over, and thus change the sea battle into a land battle. After their first great naval victory the Roman consul Regulus boldly crossed over to Africa and inflicted several defeats upon the enemy in their own country. But the following period of the war again made Sicily the scene of the contest.

The Carthaginian hero Hamilcar established himself with a small force upon the summit of a rugged mountain, and for six years kept large Roman armies in check. His troops grew their own food on the slopes. Unexpectedly, he would swoop down, eagle-like, to strike telling blows — earning from friend and foe the surname Barca, “Lightning.” Through lack of naval ability in the commanders the Romans lost four fleets with armies on board. One sixth of her citizens had perished. The treasury was empty. In this critical time private capital came to the rescue. Lavish loans built and equipped a fleet of two hundred vessels, which won a brilliant victory. This ended the war.

236. Peace. — Carthage gave up all possessions in Sicily. King Hiero of Syracuse, who had been a faithful ally of Rome, retained his dominions. The rest of the island became Roman. It was the first land outside of Italy to which Roman dominion extended. It was not admitted in any way into the Roman system which existed in Italy. It became a Roman province. (The manner of government of provinces will be explained in § 265.) Besides giving up Sicily, Carthage paid a very heavy war indemnity.

237. Between the First and the Second Punic Wars the Romans made several important conquests. They put down a revolt of Carthaginian mercenaries in the islands of Corsica and Sardinia, forced the Carthaginians to pay the cost of the expedition, and then, contrary to right and justice, retained the islands for themselves. They defeated a band of pirates in Illyricum, on the Adriatic, who had greatly disturbed Greek commerce, and though they occupied no new territory, they taught the Greek cities to look to Rome for aid against oppression. And when the Gauls to the north, alarmed by the establishment of colonies near their border, invaded the Roman domain, the Romans in a vigorous campaign subjected Gaul as far as the Alps.

THE SECOND PUNIC WAR, 218-202 B.C.

238. The Barca Family — Carthaginian Conquest of Spain. —

The cause of the enmity between the great rivals, Rome and Carthage, had by no means disappeared. On the contrary, the Carthaginians were more than ever resolved to humiliate the proud Italian city. The high-handed manner of Rome in dealing with Sardinia and Corsica embittered them still more. Hamilcar Barca was the real embodiment of this hatred. But his practical mind showed him that for the present there could be no question of a war of revenge. To offset the loss of the islands he resolved to conquer Spain. Spain’s rich mines would furnish the needful wealth, and its hardy tribes if disciplined would make an excellent soldiery. Before he left, he led his son Hannibal, a boy of nine years, to an altar and made him swear eternal hatred of Rome.

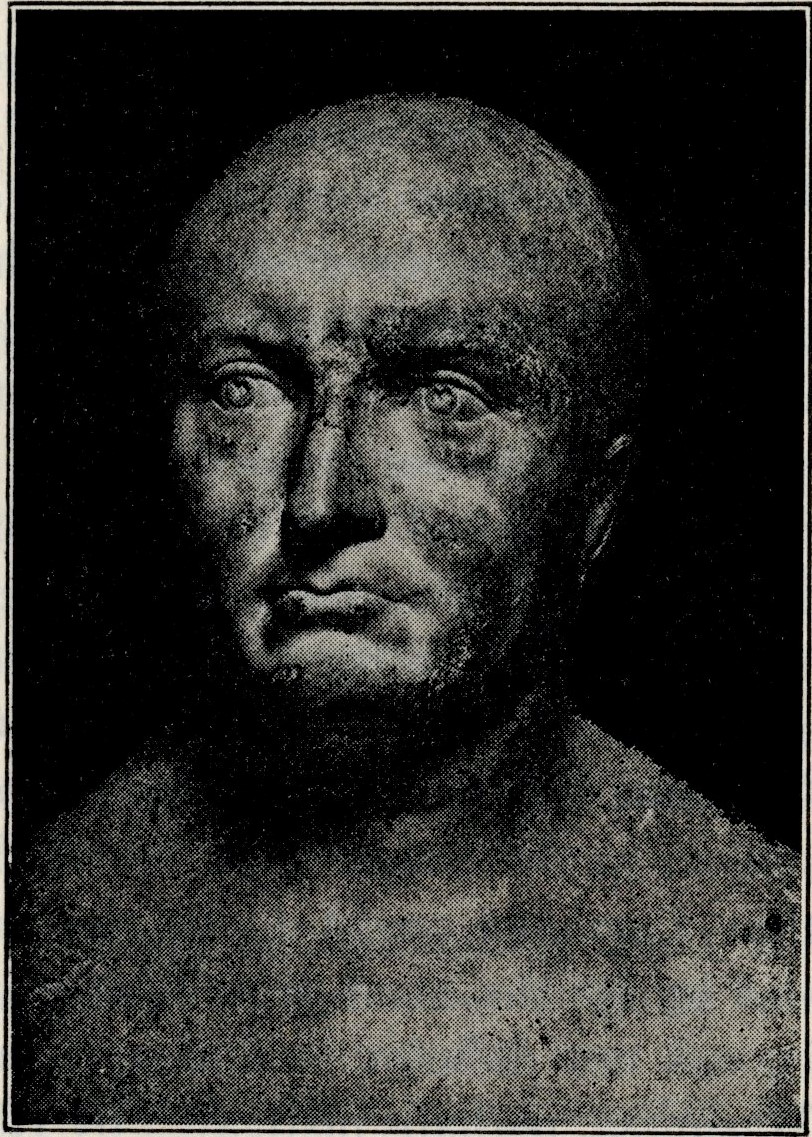

The conquest of Spain proceeded quickly. Hamilcar was succeeded by his son-in-law Hasdrubal. After Hasdrubal’s assassination Hannibal, then at the age of twenty, took the reins of power into his hands. He was already the idol of the soldiers. Rarely have men been as able as he to hold the enthusiasm of hired troopers. He was both a statesman and a general of the highest order. Roman historians, the only ones that tell of him, sought to stain his fame with envious slander. But through it all his character shines out chivalrous, noble, heroic, radiant in patriotism, and pathetic in misfortunes.

239. Occasion of the Second Punic War. — When the Carthaginian dominion in Spain extended with an ominous rapidity, the Romans forced an agreement upon Hasdrubal that the Ebro River should be the ultimate boundary. Contrary to this they themselves concluded an alliance with Saguntum, south of the Ebro. Hannibal, however, attacked that city. Thereupon Rome demanded that Saguntum be left alone, and that Hannibal be surrendered to them. This, of course, was refused, and Rome declared war.

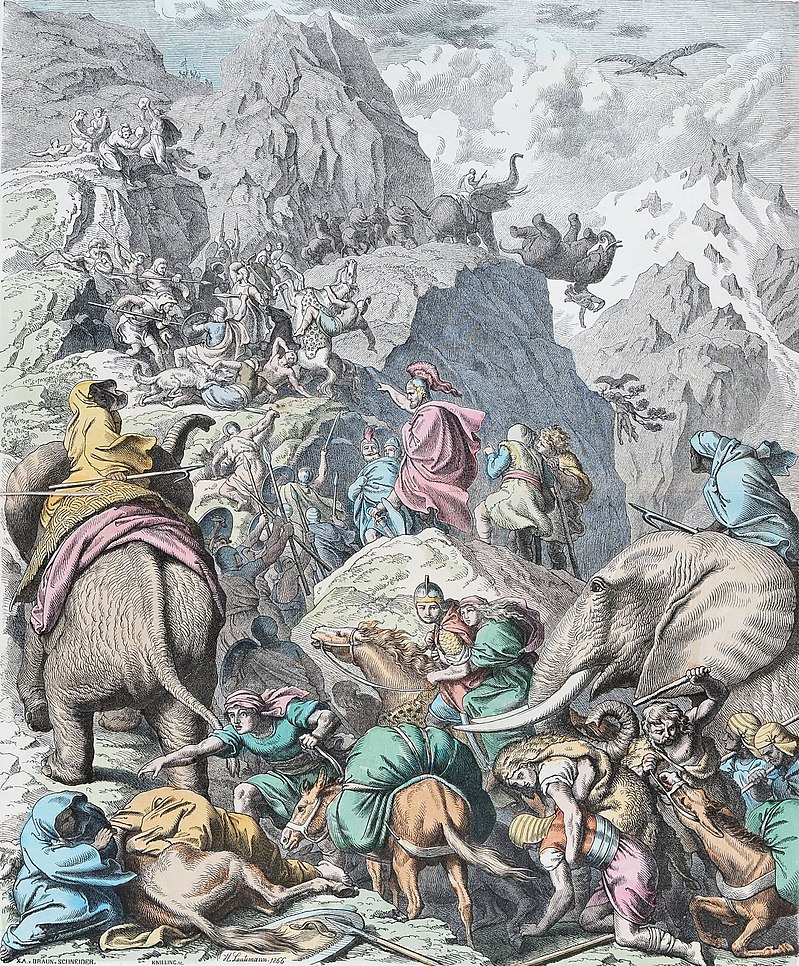

240. First Period: To the Battle of Cannae. — The Romans evidently thought that Hannibal would sit still in Spain and wait for them to come and attack him. They dispatched one consul to Sicily with orders to cross over to Africa; and the other to Spain. Meanwhile Hannibal, at the head of a hundred thousand

men, had left Spain, crossed the Pyrenees, fought and bought his way through southern Gaul, and now the news came to Rome, like a thunderbolt, that he was already in the valleys of the Alps on his way to Italy. Hastily the consuls returned, to meet with two defeats at his hands in the valley of the Po. The Gauls of that wide country, just subdued forcibly by Rome, received Hannibal as deliverer and flocked to his standards. The following spring he marched south, ambushed a Roman army of forty thousand men blinded with morning fog on Lake Trasimene, and annihilated it completely.

The Roman allies, however, instead of following the example of the Gauls, remained faithful to Rome, though Hannibal returned their prisoners to them without ransom, and spared their territories, while he frightfully devastated those of the Roman citizens. He could not think of attacking Rome. He marched through the hill country down to the south. For some time a Roman dictator, Fabius Maximus, kept him at bay by following him closely and inflicting losses upon him, but avoiding a pitched battle.

241. The Battle of Cannae. — Fabius, surnamed Cunctator, the Laggard, was succeeded by two consuls who were more convinced of the invincibility of the Roman army. They followed Hannibal to Cannae, and forced him to battle. He had only forty thousand men against their ninety thousand. But he never attacked as his enemies expected. Within a short time the whole Roman army was entirely surrounded, and then began “a carnival of cold steel, a butchery.” Hannibal lost six thousand men, the Romans eighty thousand in prisoners and dead. It was the most terrible defeat the Romans had ever suffered. A fifth of the fighting population, a fourth of the senate, nearly all the officers, and one of the consuls had perished.

242. The Romans after the Battle of Cannae. — The sterling character of the Romans never showed more gloriously than after this terrible blow. Although most of the allied tribes and cities of the south of Italy, among them the mighty Capua, now joined the invader, Rome refused to treat with Hannibal, even about the exchange or redemption of the captives. Instead of recalling their small forces from Sicily and Spain, they increased them considerably, and began to wage war vigorously in these distant lands. By superhuman exertion they raised their fighting strength to 150,000 men.

The Carthaginians meanwhile lost their opportunity. The aristocrats of Carthage had never had much liking for the Barca family. They left Hannibal without further support, and did little for the protection of Syracuse in Sicily, which had concluded an alliance with them. They made no effort to regain their superiority at sea.

In constant minor war operations Hannibal’s forces slowly dwindled away, and he tried in vain to strengthen them by alliances with other states. The Romans took Syracuse after a three years’ siege and reduced it to a condition in which it was no longer a commercial rival of Rome. New forces were hurried over to Spain, after Hannibal’s brother, Hasdrubal, had inflicted a dreadful defeat upon the Romans. The Romans laid siege to Capua, which Hannibal had made his headquarters. To draw the besiegers away he marched against Rome itself and ravaged the fields to its very walls. There was a terrible fright in the city. The cry, Hannibal ante portas, “Hannibal is before the gates,” remained for centuries the expression for the highest degree of danger. But the Senate did not lose its head. Just then an army was dispatched to Spain. Hannibal was too weak to undertake a real siege or even an assault. The Romans did not give up the siege of Capua, and that city soon paid by a fearful punishment for its defection.

243. The Last Efforts of the War. — In Spain Hasdrubal had meanwhile gathered another large army, had eluded the Roman commander, and had set out to join his brother in Italy. The Romans captured a messenger with communications for Hannibal, telling him of the details of Hasdrubal’s approach. They immediately turned against the new invader with overwhelming forces, and defeated and killed him on the Metaurus River in 207 B.C. When Hannibal saw his brother’s head thrown with brutal barbarity into his camp, he exclaimed, “Now I see the fate of Carthage.” He was right. After a few more years, Carthage was obliged to call him to the defense of her own walls, because a Roman army under Publius Cornelius Scipio had landed in Africa. With tears in his eyes he left the land in which for seventeen years he had been fighting and conquering, unvanquished on the field of battle, but betrayed by the apathy and envy of his own countrymen. At Zama he met his first and last defeat.

244. Peace — 201 B.C.— Rome imposed cruel conditions. Carthage had to give up all her possessions outside of Africa; deliver up her warships save ten; pay a huge war indemnity which was intended to keep her poor for many years; and promise to wage no war except with Rome’s permission. Rome was now the undisputed mistress of the western Mediterranean. She honored the victorious Scipio by bestowing upon him the surname Africanus.

245. Between the Second and the Third Punic Wars Rome secured and extended her conquests. Several cruel campaigns “pacified” Cisalpine Gaul in the region of the Po River. Roman bravery and generalship and their breaking of the most solemn pledges secured the submission of Spain; and Roman colonies and commerce served efficiently to Romanize the land and the people. By a friendly alliance, concluded years before, the acquisition of southern Gaul was prepared, which country in due time also became a Roman province.

THE THIRD PUNIC WAR

246. Cause and Occasion. — Under the able administration of Hannibal, Carthage began slowly to recover her prosperity. Though the taxes were not raised she paid her war indemnity regularly. The lower classes of the citizens were admitted to participate in political life. Her commerce, too, increased noticeably. Meanwhile in Rome the merchant class, using the enormous opportunities created by the latest wars, grew in importance, and viewed with envy the new success of the rival. The old senator, Porcius Cato, the living embodiment of all that was great and mean in the Roman character, saw with his own eyes, on the occasion of an embassy, the flourishing condition of Carthage. From that time on he concluded every speech on any subject in the Senate with the words: “and for the rest I think that Carthage ought to be destroyed.” Commercial rivalry was by far the most prominent cause of the Third Punic War. It was not difficult to find an occasion. The Numidian king, Masinissa, perhaps instigated by Rome, took piece after piece of Carthaginian territory. Roman embassies, sent to investigate, invariably declared Carthage in the wrong. Finally Carthage, contrary to one of the conditions of the peace, went to war against Masinissa, and sent an embassy to Rome to explain the matter. Rome was glad. It declared war without delay.

247. The Third Punic War. — A formidable army of 80,000 men landed in Africa. The trembling Carthaginians were told to deliver all their warlike stores. In long lines of wagons 200,000 stands of arms with vast military supplies were sent to the Roman camp and all their shipping was surrendered. Then came the final verdict: Carthage must be abandoned; the citizens may settle in four open villages, eighty stadia (about ten miles) from the sea.

Despair blazed into passionate wrath, and the Carthaginians chose death rather than ruin and exile. The town became one huge workshop. Rich and poor and slaves labored feverishly. Women gave their hair for the strings of war engines. The temples and houses were dismantled for timber and metal. Carthage stood a four years’ siege, holding out heroically against famine and pestilence. But the end was inevitable, though the Romans had to conquer the city house by house. Publius Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus, nephew and adopted son of the first Scipio, was the conqueror. By express order of the Senate, Carthage was given to the flames, and what was left of the population was sold into slavery.

It was the end of Carthage. Its territory became a Roman province under the name of Africa. The disappearance of Carthaginian commerce meant an enormous profit for the Roman merchants and money kings, who thus were rid of a most powerful competitor. — The younger Scipio too received the surname Africanus.

While we condemn the brutality and faithlessness by which the Romans did away with the African rival, we cannot but recognize that unwittingly they bestowed a benefit upon mankind, and upon Europe in particular. A victory for Carthage would have been a calamity for true culture. It would have brought to posterity the cultural elements of Asia, which were by far inferior to those of Hellas. Our civilization was destined to come from Greece.