The following is an excerpt (pages 160-172) from Ancient and Medieval History (1946) by Francis S. Betten, S.J. Although some information may be outdated, the Catholic historical perspective it provides remains pertinent. Use the link at the bottom of post to read the previous/following pages. Use the Search box above to find specific topics or browse using the Resources tab above.

CHAPTER XVII

FORMATION OF THE ROMAN CONSTITUTION

ROME UNDER KINGS

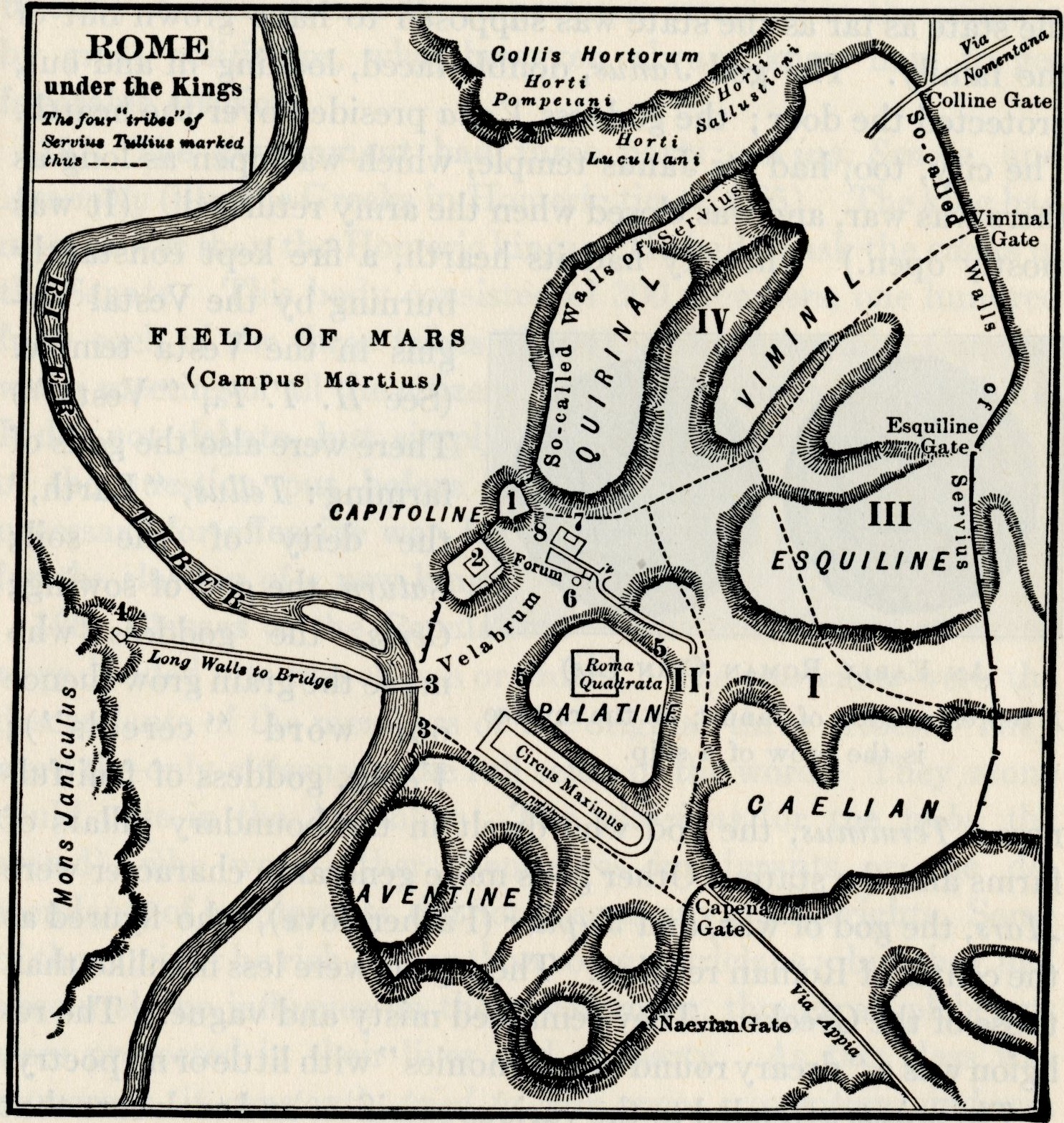

194. The City on the Seven Hills. — The thirty tribes of Latium, each settled around some hill fort, formed an alliance which was both religious and political. Its head was Alba Longa (the Long White City). Rome, too, in the beginning seems to have consisted chiefly of a fortified settlement on the Palatine Hill, often referred to as Roma Quadrata, “Square Rome.” Walls have been discovered there which must reach back to about 1200 B.C. There seems to have been an early settlement of an Etruscan tribe on the Quirinal Hill, and another of a Sabine tribe on the Caelian Hill. Eventually these three, no doubt after a period of strife, found it advisable to unite under one king on an equal footing. They chose the low ground between the hills as a place for political assemblies and as a common market. They fortified the steep Capitoline Hill, made it a common fortress, and erected a long-stretched wall around all these parts, which inclosed very much open space, thus providing for an increase in population. This wall was said to be the work of a King Servius Tullius. But the present remains are certainly of a later date.

The amalgamation of three tribes into one community indicated the policy of the Romans for part of their career. Rome grew principally in this way. Only the new members were not always admitted on a footing of equality.

The Year 753 B.C. is given by Roman authors as the date of the foundation of their city. This is indeed the year which we must mark for that event, because at one time some Romans and many later authors after them counted the years from it, as we do from the year of the Birth of Christ. (See H. T. F., “Era,” 3.) But this year is by no means certain.

195. Early Conquests. — The new community was aggressive. Before the year 510 B.C. Rome had acquired by wars with the neighboring Etruscans, Sabines, and Latins the whole south bank of the Tiber from the sea to the highlands, and about one third of all Latium. The inhabitants of destroyed towns had been brought to Rome. Even Alba Longa was destroyed, and Rome succeeded to the headship of all Latium. Thus the open spaces inside the city walls were gradually settled with newcomers. (Rome became the “City of Seven Hills.”)

196. Roman religion centered around the house, and around the state as far as the state was supposed to have grown out of the family. The god Janus, double-faced, looking in and out, protected the door; the goddess Vesta presided over the hearth. The city, too, had its Janus temple, which was open as long as there was war, and was closed when the army returned. (It was mostly open.)

The city had its hearth, a fire kept constantly burning by the Vestal Virgins in the Vesta temple. (See II. T. F., “Vesta.”) There were also the gods of farming: Tellus, “Earth,” the deity of the soil; Saturn, the god of sowing; Ceres, the goddess who made the grain grow (hence our word “cereals”); Venus, goddess of fruitfulness ; Terminus, the god who dwelt in the boundary pillars of farms and the state. Other gods more general in character were Mars, the god of war, and Jupiter (Father Jove), who figured as the center of Roman religion. These gods were less manlike than those of the Greeks. They remained misty and vague. The religion was a “dreary round of ceremonies” with little or no poetry.

The priests attended to the various sacrifices and took care that the festivals were celebrated on the correct dates. This gave them charge of the Roman calendar (H. T. F., “Calendar,” 3.) The augurs found out the will of the gods from auspicia, that is, the flight or cries of certain birds, or their conduct when feeding. Priests and augurs were state officers. (The haruspices, who told the will of the gods from the color or size of the entrails of sacrificial animals, were a sort of private soothsayers, but were often employed on political occasions.) Auspicia had to be taken officially before every state action — for instance, before elections of any kind. The common people believed that once the gods had declared their will, it was a duty to carry it out. Hence the importance attached to the auspicia by great politicians, who, however, always knew how to get favorable auspicia.

197. The government had three parts: King, Senate, and Assembly (like the Greeks in Homeric times, § 85). The king had more power than the Homeric kings. He had to ask the advice of the Senate. This body consisted of 300 members, one hundred from each of the three tribes (§ 194). The Assembly, Comitia, was a meeting of all the citizens. It met at the call of the king. It did not debate, but simply expressed approval or rejection of the question put before it by the king. Its consent was necessary for offensive war, for any change in old customs, and for the election of a new king.

198. Classes of the Population. — The inhabitants of Rome were divided into two classes or orders. The patricians were the descendants of the members of the original three tribes. They were the only citizens in the full sense of the word. They alone could vote in the Assembly. The plebeians (or the plebs, the crowd), who were either themselves immigrants or the descendants of immigrants, did not possess any citizen rights. Some of them might be rich, richer than some patricians; but they had absolutely no influence on the government, though all plebeians were protected in their lives and property. As this class was numerous, it constantly tried to gain more recognition, and win rights and privileges. This endeavor makes part of the early political history of Rome. One of the greatest difficulties against their adoption to citizenship was the fact that they were looked upon as an unholy mob, which had no share in the family and clan worship of the patricians.

199. Patrician society was organized in families, clans, and curias. The family was almost a state in itself. The father ruled his household and even the households of his male descendants as priest, judge, and king. He could sell or slay his wife or any of his children, without incurring any guilt before the law. Of course no father was inclined to make use of this power. It is a curious fact that despite this legal slavery of women, the Roman matrons had a dignity and public influence unknown in Greece. When a daughter married, she left the family entirely and came under the control of her husband or her husband’s father. A patrician could not marry a plebeian woman. If he did, he was cast out from his family and became a plebeian. The Roman clan, called in Latin gens (plural, gentes), was supposed to have grown out of the family. There were 300 such gentes in ancient Rome. The gentes were grouped into 30 curias, ten to each of the three tribes. Each curia had its own religious festivals. In the assembly, the citizens, i.e., the patricians, met by curias, each curia having one collective vote. Thus it could happen that five men of one curia had as much voting power as a hundred other men, if these all belonged to one other curia.

TWO CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGES

200. A New Military Organization of the People. — Originally the army was made up of the patricians and their immediate dependents only. The plebeians were not allowed to bear arms. But as they gradually increased in number and wealth, it appeared desirable to enlist them also. So one of the kings — according to legend his name was Servius Tullius — introduced a new division of the entire people including the plebeians, without, however, abolishing the ancient curias of the patricians.

The new division was based on wealth, not on birth, on the ground that every soldier had to pay for his own equipment. There were five classes. The richest had to serve in the fullest kind of armor. The second and third, though less fully equipped, were also counted as “heavy-armed.” The fourth and fifth figured as “light-armed.” Each class was subdivided into companies supposed to count one hundred each, and therefore called centuries, from the Latin word centum, a hundred. The very richest men, however, who served on horseback and therefore had to maintain horses, were called “knights,” and with their eighteen centuries formed almost a class by themselves. There were in all 193 centuries. (Compare with the four classes at Athens, § 101.)

Since with the ancients the obligation to bear arms and the right to vote always went together, there was now established a second assembly, called the Assembly of the Centuries, for all men whether patricians or plebeians. Each century had one collective vote. This Assembly of the Centuries decided chiefly on political matters, which were thus withdrawn from the Assembly of the Curias.

At first sight this would seem to mean a great deal for the plebeians. In reality it did not amount to much. The centuries were not equally divided among the several classes. The first class, which consisted chiefly of patricians, had eighty, each of which as a rule numbered fewer than a hundred men. The centuries of the lower classes commonly counted many more than a hundred men. The knights and the first class together possessed 98 votes. If they voted in a body, they could carry any measure they pleased. After Roman custom the voting stopped as soon as there was a majority. So it could happen that the second and following classes, which consisted more and more of plebeians, did not even come to cast their vote at all.

Despite this great drawback the new arrangement was an advance. It was the first break in the barrier between patricians and plebeians.

201. The Disappearance of Royalty. — Probably more than the traditional seven kings ruled in Rome. (See Ancient World, § 335.) The last three seem to have been “tyrants” in the good sense of the word. They carried out great buildings and other works for the benefit of the city. They greatly favored the plebeians. Servius Tullius was the last but one. We are ill informed about the details which led to and accompanied the expulsion of the last king, Tarquin, surnamed the Proud. Historians have no doubt that it was the doing of the patricians. At any rate the patricians were the ones that gained by the change of government, as the following pages will amply show. Rome became a republic. This is said to have happened in 510 B.C., the same year in which Hippias was driven out of Athens (§ 106).

The main sewer of Rome, built by Etruscan masters, as it appeared in 2019.

202. The chief features of the republican government, which in substance remained for centuries, were these:

(a) Two consuls were elected from the patricians to rule simultaneously for one year. They possessed the full royal power as rulers and judges. They were not priests, however. The priestly functions were intrusted for life to one who continued to be called “king,” rex. The consuls called and dissolved the Assembly at will. They alone could propose measures or nominate magistrates. They ruled the city in peace, and commanded the army in war. In actual administration they changed off every month. As a mark of their dignity twelve “lictors,” who carried the “fasces,” that is, bundles of sticks with an ax in them, preceded in single file the consul who was officiating that month, while an equal number followed the other.

The power of the consul was limited in several ways. Each consul at all times had the right to forbid any measure which the other one wished to take. When they laid down their offices, they might be tried and punished by the Assembly of the Centuries for what they had done while in the office. Their short term, moreover, made them dependent upon the advice of the permanent Senate, against whose will it was almost impossible for them to act. Finally, while in the beginning there was no appeal from their verdict as judges, they could not later on condemn a citizen to death without the approval of the Assembly of the Centuries.

(b) The Senate and the Assembly remained as before. But the Senate’s power grew by the fact that the consuls were more dependent on its “ advice ” than the life-king had been. On the other hand, the consuls filled the vacancies in the Senate that occurred during their year of office.

(c) The dictatorship was an extraordinary office for times of great danger. It might happen, in a war for instance, that the two consuls with their different opinions were not likely to carry on a strong attack or defense, while it was necessary to follow one plan strictly and in every detail. In such cases either of the consuls, upon the request of the senate, might appoint a dictator, who remained in office as long as the case required, though not longer than six months. During this time he was the sole master of Rome, and at full liberty to take any measure he thought to be necessary to keep the state from suffering harm. He was independent of Senate and assemblies. Dictators were appointed repeatedly, and always with good results.

IMPORTANT GAINS OF THE PLEBEIANS

203. Condition of the Plebeians. — The expulsion of the kings enhanced the power of the patricians. They alone could hold any office, and the importance of their senate had risen enormously. The plebeians had won nothing. On the contrary they had lost a protector, and were delivered over entirely to the patrician government. They had in particular three grievances:

(a) The exclusion from public lands. The Roman state possessed extensive farm lands, acquired mostly by conquest. The kings had permitted the plebeians to settle on these lands, though the greater part was used by the patricians. Now these domains were closed to the plebeians. The patrician officers even neglected to collect the small rent which the patricians were bound to pay to the state for the public lands they held.

(b) Their unjust debts. When the plebeian served in war, he had to neglect his farm, or he might find it devastated by the enemy. He was forced to borrow money or grain. Maybe this happened several years in succession. Thus his little farm became heavily mortgaged. According to Roman law the creditor might take away his farm, or throw him into a dungeon, or sell him, his wife, and his children into slavery. The large number of such debtors made this a crying evil.

(c) The laws were not written. In case of an injustice done to him the plebeian had to recur to the patrician judge, who was not only partial to those of his class, but also decided the case according to laws which the plebeian was not supposed to know. So even in the courts of justice the plebeian was completely helpless, and saw himself surrendered to the mercy of a prejudiced judge.

Even the rich plebeians were utterly dissatisfied with their lot. This was especially true of the descendants of the ruling families of conquered towns, who had been forced to come to Rome. They felt sorely grieved, because they now belonged to a class looked upon as inferior and unfit for any office. These became the natural leaders of the downtrodden plebeians.

204. The Struggle. — Years of the fiercest civil dissension were the result. Repeatedly the anger of the plebeians broke out into violence against those whom they especially charged with oppression. Several times they drove a consul, after his term of office, out of the city. The patricians replied by similar acts, in particular against those of their own number who were large- hearted enough to see the injustice of the treatment meted out to the plebs. In 494 B.C. the plebeians had received the solemn promise that their grievances would be redressed if they would go to war that year. Once before this promise had been given and broken. This time, too, they found, when returning from the war, that nothing was going to be done for them. Thereupon, armed as they were, they left the city, threatening to build a Rome of their own on the “Sacred Mount,” some three miles away. No power of persuasion could induce them to return before a great concession had been made. A new office was created for their protection.

205. The Tribunes of the Plebs. — The plebeians were to elect from their own number two (later on ten) men vested with a very peculiar power. Whenever a plebeian thought he was wronged by any magistrate, he could appeal to a Tribune of the Plebs, who might stop the official by calling out, veto, “I forbid.” So that they might always be within reach, the tribunes were forbidden to leave the city, or to lock the doors of their houses by day or night. Later their power increased, so that they could even “veto” state actions, such as the proposing of a law in the Assembly, or the passing of a Senate’s decree, if they thought it would be harmful to the interests of the plebs. This power was indeed such that the tribunes could bring the whole government to a standstill. It is highly to the credit of the Roman people that on the whole the Tribunes of the Plebs used their privilege with moderation.

206. Written Laws. — It took nearly a half century of agitation to force the patricians to consent to the writing down of the laws. Tradition combines it with another emigration to the Sacred Mount. A “Commission of Ten” (Decemviri, ten men) was appointed for this purpose. These officials had the existing laws engraved on twelve tables, which were set up in the market place. The “Laws of the Twelve Tables” were the beginning of Roman legislation. They were very harsh. But at least everybody could see for himself how the judges were required to decide, and these laws applied equally to patricians and plebeians. This event is placed in 449 B.C.

207. A Third Assembly. — Under the kings the whole state had been divided into twenty sections, called “tribes,” four of which were in the city. (They had nothing to do with the three original tribes of the patricians, §194.) Since the plebeians had no organization like that of the patrician curias, they had gradually begun to gather in an assembly of their own, in which the vote was taken by tribes. Though according to Roman views the patricians could not be kept out of these meetings, the Assembly of the Tribes became essentially a plebeian gathering. With the introduction of the Tribunes of the Plebs it acquired greater influence. It elected these officers, who afterwards had the right to summon it and to preside in it. Its decrees were binding upon the whole plebs. At a much later date, laws thus passed, called plebiscites, became binding upon the whole people, like those of the Assembly of the Centuries, subject, however, to the Senate’s veto. (H. T. F., “Plebiscite.”)

FULL EQUALIZATION OF PLEBEIANS AND PATRICIANS

208. Patrician Evasions. — The plebeians rightly remained dissatisfied. The harsh debtor laws were not abolished. Nor did the patricians stop occupying almost exclusively the public lands. In 445 B.C. the plebeians had the satisfaction to see the prohibition of marriages with the patricians repealed, a step which made possible the social fusion of the two orders. But their aim was admission to the consulship.

The patricians did not want to see the religious office of the consuls polluted by unholy plebeians. They perceived at the same time that some concession had to be made. So they separated the religious functions and some political powers from the consular office and gave them to new officers, the censors, who were to be patricians. Two censors were chosen every five years. Among other duties they revised the lists of the citizens and might strike out a citizen’s name from them; they might deprive a knight of his rank; they filled the vacancies in the Senate, and expelled unworthy senators. There was no appeal from their verdicts. When all this business was finished, which commonly took some eighteen months, they offered up a sacrifice for the propitiation of the gods. This important and mighty office was always much respected and looked upon as the most dignified in the state.

The consulship thus shorn of its highest privileges was to remain patrician nevertheless. Instead of consuls certain other officers were to be elected, who might be taken from the plebeians. As a matter of fact few plebeians secured this selection. For some eighty years the quarrel went on with the old fierceness, the patricians not shrinking even from bloodshed.

209. The Licinian Laws. — Nevertheless the power of the plebs increased. In Licinius Stolo they found an able champion, who led them to victory. In the year 367 B.C. the “Licinian Laws,” named after him, went into force. The most important of them were these three:

(1) From now on consuls will be elected, and one of them must be a plebeian.

(2) No citizen will be allowed to hold more than 500 jugera (about 300 acres) of public land.

(3) The payment of debt is to be postponed for three years, and the interest already paid is to be deducted from the capital.

The student will perceive that the first law is political, the second and third economic (§ 104). The third law offered only a temporary remedy for a crying evil. The second bid fair to end a great deal of misery among the poor, who now could hope to get a share in the public domain. Let us keep this law in mind. Two hundred years later it will again loom up big on the horizon of the economic world of Rome.

210. Final Plebeian Successes. — The patricians had again separated part of the powers of the consul from that office and had created the patrician office of praetor for the functions of supreme judge. Thus three great offices remained closed to the plebeians, namely, those of dictator, censor, and praetor. All these devices were in vain. The plebeian consul was the entering wedge. It was the consuls that proposed the names of candidates for all elective offices and at critical times appointed the dictator. So it was only a question of time, when these positions, too, would be filled by plebeians. As a matter of fact by the year 300 B.C. all offices, including even those of priests and augurs, and the Senate itself, were open to the plebs.