The following is an excerpt (pages 173-185) from Ancient and Medieval History (1946) by Francis S. Betten, S.J. Although some information may be outdated, the Catholic historical perspective it provides remains pertinent. Use the link at the bottom of post to read the previous/following pages. Use the Search box above to find specific topics or browse using the Resources tab above.

CHAPTER XVIII

UNIFICATION OF ITALY

CONQUEST OF ITALY

211. Events before 367. — The expulsion of the kings in 510 was followed by a weakening of Rome’s exterior power. She even lost territory to neighboring peoples. But when the interior struggles were abating, in 449, Rome made slow gains. In 396 she destroyed Veii, a dangerous Etruscan rival, and brought its inhabitants to Rome. In 390 the Gauls from the north (§ 192 c) approached Rome, and defeated a Roman army on the Allia River, some twelve miles from the city. Rome fell into their hands, with the sole exception of the Capitol (see map on page 161), which was bravely defended by an heroic garrison under Marcus Manlius. Having plundered and partly destroyed the city, the Gallic hordes left after seven months.

212. THE ITALIAN WARS. — By the Licinian Laws the process of unification within Rome had come to a close. Patricians and plebeians now formed one Roman people. United Rome turned to the work of uniting Italy. This task filled a century, about 367-266, a time during which the Romans performed deeds of the greatest valor and showed a wonderful determination and admirable consistent statesmanship, though we cannot say that all their wars had a just cause or that Rome always made a moderate use of her victories. We enumerate only the most important conflicts.

213. The Latin War, the last attempt made by the cities of Latium to gain equality with the city on the Tiber, in 338 ended in a complete victory for Rome. Rome dissolved the Latin confederacy, and concluded a separate treaty with each city. The inhabitants of some became Roman citizens, and were listed in the Roman tribes. Others were made subjects, but in different degrees, so that there was no common interest to bind them together. Their inhabitants were not allowed to carry on commerce with those of other towns except through Rome.

214. Wars with the Samnites. — The Samnites were less civilized, but brave, warlike, and strongly attached to their land and liberty. They were numerous enough to be a match for Rome. Before the Latin War there had been a first war between the two powers, but with no gain for Rome. In 326 Rome provoked the Samnites into a declaration of a second war. Smaller nations joined both parties. Fortune varied greatly. Rome suffered terrible defeats, without, however, even considering the giving up of her aim. During the second war she tried, more than she had done before, to secure her conquests by the foundation of fortified colonies in important localities. At the end of this war, 304, the Samnites, besides giving up much of their possessions, were forced to become “allies” of the Romans.

The third Samnite war was in reality fought by a coalition of Samnites, Etruscans, Gauls, and minor nations. It was almost a war of Italy against Rome. It brought Rome to the verge of ruin. But undaunted bravery and excellent generalship decided for Rome. By 266 all central Italy had come under her control. She organized it into one state. As in the case of the Latins (§ 213) she gave various rights and privileges to the cities and regions, so as to make impossible a unity of interest. Numerous strong Roman colonies helped to secure the permanence of Roman dominion.

215. The Conquest of Southern Italy. — Rome had her eye on the cities of Magna Graecia. Contrary to a treaty Roman ships entered the harbor of Tarentum and were destroyed by the infuriated people. When Rome sent an envoy to settle the dispute, the mob grossly insulted him, whereupon war was declared. The Tarentines, too unwarlike themselves, sought help from Pyrrhus, the chivalrous King of Epirus on the other side of the Adriatic.

Pyrrhus was a distant relative of Alexander the Great. He had been forced to give up the throne of Macedonia, and now wished to become an Alexander in the West. He hoped to unite the Greek cities in Italy and Sicily against Carthage. He landed in Italy with an excellent army. He defeated the Romans in two battles. In the second his own losses were so great that he exclaimed, “One more such victory, and I am lost.” But when he offered a favorable peace, the Roman Senate replied that Rome would not treat with an invader as long as he stood on Italian soil. In a third battle he was completely conquered. He left the Greek cities to the Romans to be incorporated into their Italian state.

GOVERNMENT OF ITALY

The inhabitants of Italy, about 5,000,000, fell into two classes: the ruling community of Roman citizens numbering about 1,400,000, and the subjects outside the Roman state proper.

216. The Roman citizens enjoyed the four rights of Roman citizenship: —

Private rights: (1) To hold property in any of Rome’s possessions ; (2) to intermarry in any Roman community;

Public rights: (1) To hold office in Rome; (2) to vote in Rome.

The badge of the possession of these rights was the enrollment in one of the tribes. The number of the tribes had been increased to 35. Whereas at the time of the organization (§ 207) a man could transfer himself to another tribe simply by moving into it, now those once enrolled in one tribe remained with it no matter where they fixed their abode, and their descendants, too, became members of the same tribe.

Only a small number of the citizens actually lived in Rome or in the neighborhood. Many dwelled in places called municipia and Roman colonies. The municipia were cities acquired by peaceful means or otherwise, which had been given full citizenship. The Roman colonies were founded by settling Roman citizens in some important spot, chiefly for military purposes. The colonies helped to make rebellions of the subject nations impossible. Both municipia and Roman colonies enjoyed home rule, that is, they controlled their local affairs independently of Rome. However, if they wished to make use of their right to vote, they had to go to Rome. (See § 109, and H. T. F., “Representative Government.”)

The organization of bodies like the municipia and Roman colonies with the privilege of local self-government is a new contribution to the art of ruling. The municipia in particular had another advantage in that they were a means of increasing the number of citizens. Athens, which had something like colonies in its cleruchies (§ 107), never admitted allied or conquered cities to full citizenship as the Romans did in the case of municipia.

217. The subject communities differed greatly in the possession of privileges. There were three classes: —

(a) The Latin colonies differed from the Roman colonies in that their inhabitants possessed only the private rights of Roman citizenship, though they enjoyed complete home rule. The Latin colonies, too, were founded for the defense of threatened localities, often in the heart of a subjected nation, in order to prevent attacks and risings. The colonists came from the poorer Roman citizens, who gladly gave up their public rights in return for a substantial farm. — Both the Roman and the Latin colonies spread the views, customs, and language of Rome through all the parts of Italy and thus greatly promoted the unification of the peninsula.

ROMAN ROADS

(b) The allies, the most numerous class among the Italians, had neither the private nor the public rights of citizenship, but retained self-government in local affairs. Each city or tribe was individually joined to Rome by a special treaty, and these treaties varied widely.

(c) The prefectures were the least numerous. They were the lowest rung of the ladder. They had neither public nor private rights nor self-government. Their local affairs were administered for them by “prefects” sent from Rome.

218. Rome’s Relation to the Subject Communities. — Rome’s grasp on all the various classes of subject was firm and efficient. They were most strictly isolated. Alliances among them or with other powers and the coining of money were prohibited. Each city had to deal directly with Rome, and Rome alone. Commonly a city had not even the right to carry on commerce with any other city except through Rome. Often the roads existing between larger cities were destroyed and only those were left that led to Rome. At this time the burdens placed on the subjects were not heavy; they consisted chiefly in moderate levies for the Roman army.

On the other hand, Rome defended the interests of the subjects, kept up law and order, and made impossible the disastrous wars they had been waging formerly. It kept them in good humor by not interfering with local customs and religion, and by holding out the hope that they might rise to a higher class by good behavior and might eventually even receive the full rights of Roman citizenship.

219. The Roman roads were a very peculiar feature of the administration of Italy by the imperial city. They were devised in the first place for military purposes. During the second Samnite War Rome began the construction of the famous Via Appia, Appian Way, so named after the censor Appius Claudius, to connect Rome with Campania. Afterwards all Italy, and then the growing empire outside Italy, were traversed by a network of such roads. Nothing was permitted to obstruct their course. Mountains were tunneled; rivers were bridged; marshes were spanned for miles by viaducts of masonry. They were so well built that even to-day some parts of them are in good condition and still “mark the lands where once the Roman ruled.” Though designed as military highways, they no ‘less helped peaceful intercourse of all kinds and were one of the material links that bound Italy together (§ 71).

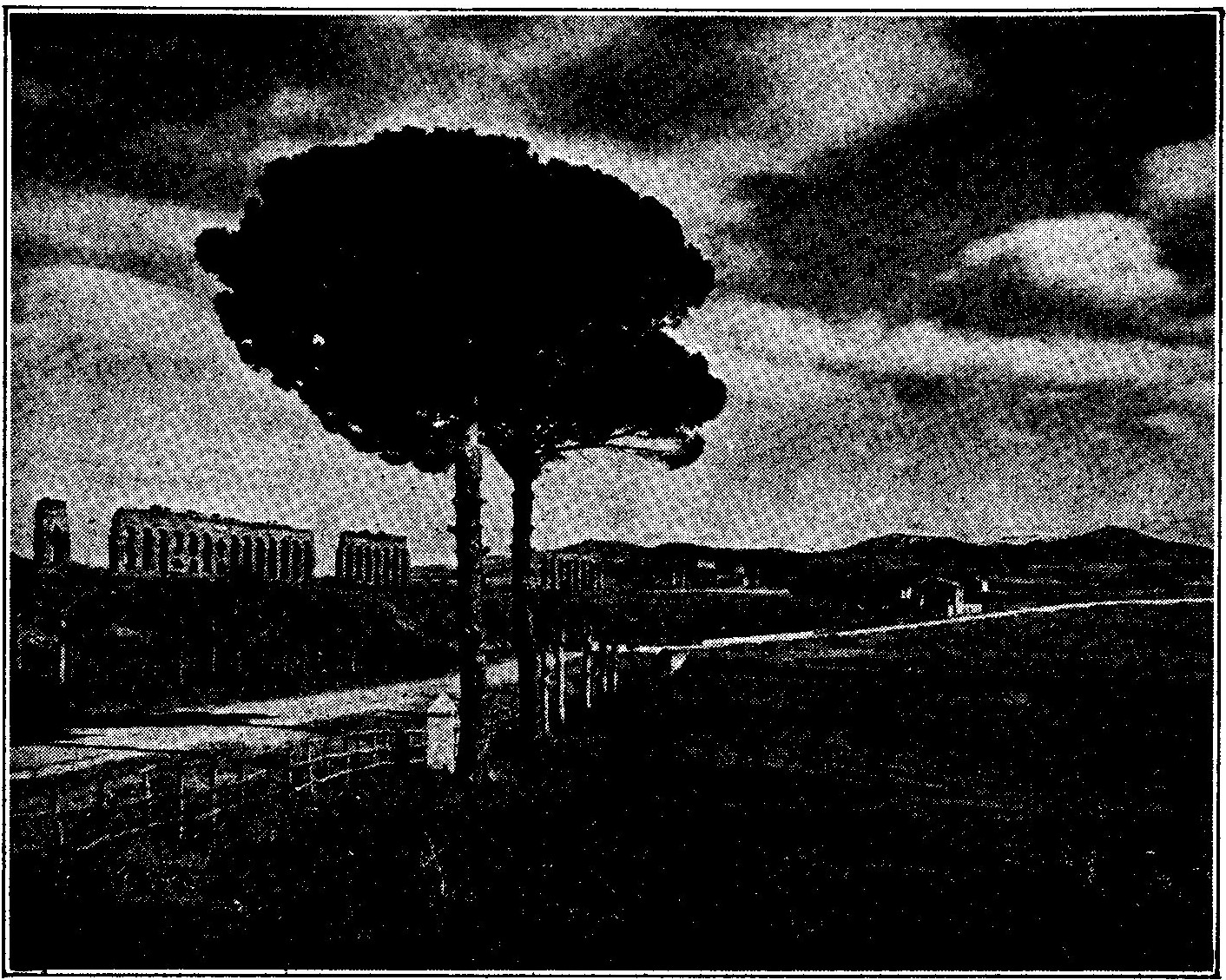

The Appian Way is in the foreground, and the remains of an aqueduct in the rear. These arches support a channel which carries the water from some good spring, often ten or more miles away, to the city. In some places the channel was on the surface, in others underground. The first such aqueduct was built in 312 B.C. At the time of the emperors the aqueducts poured every day 330,000,000 gallons of excellent water into the city of Rome

GOVERNMENT OF ROME ITSELF

220. The officers of the state were of two classes:

(1) curule magistrates, who had the right to sit in the assemblies upon the “ curule chair,” a sort of ivory campstool. They were: the two consuls, officially the heads of the state (§ 202); the two praetors, supreme judges (§ 210); the two curule aediles, with oversight over police and public works; the two censors (§ 208); and the dictator, appointed in critical times only (§ 202).

(2) Non-curule magistrates: two plebeian aediles, with duties like those of the curule aediles; eight quaestors, in charge of the treasury, and with some judicial power; the ten tribunes (§ 205). The office of the tribunes, though less in dignity than the curule offices, was perhaps the most important of all, on account of the tremendous power of veto.

221. The three assemblies continued to exist side by side. But that of the curias lost practically all its importance and its meetings were a mere formality. The Assembly of the Centuries elected consuls, censors, and praetors, all other officers being elected in the Assembly of the Tribes, in which the patricians now regularly took part.

Important changes concerning the assemblies:

(a) While formerly only the landholders were enrolled in the tribes, since 312 all the citizens were enrolled, but the landless ones were confined to the four city tribes, so that they could not outvote the rural landowners.

(b) The five classes received each an equal number of centuries and thereby an equal number of votes in the Assembly of the Centuries (§ 200).

(c) The senate lost its veto on the decrees of the Assembly of the Tribes, having lost its veto on the elections in the Assembly of the Centuries some years before.

All this meant an enormous legal gain for the democratic elements. The whole power by law rested in the assemblies, with the Senate acting as advisory board. In reality things were different.

222. The Senate. — The censors filled vacancies in the Senate from those who had held a curule office. Thus the Senate, too, was elective indirectly, though its members held office for life. Hence in that body there gathered an enormous amount of practical experience and statesmanlike wisdom, acquired especially through dealing with the complicated conditions induced by the wars. It was here that the admirable, though in many ways selfish, organization of Italy had been devised. The consuls could not afford to neglect a body so eminently fitted for advice in matters of state and in the direction of foreign affairs. Nor would they venture to propose any law or measure in the assemblies, unless it had been discussed and sanctioned beforehand by the Senate. Thus, though without the veto power on the assemblies, the Senate really controlled their proceedings. Moreover, all the curule officers hoped to get into the Senate. So they must keep on good terms with it, in order not to be antagonized when they had become members.

The javelin, not destined for thrusting but for throwing, consisted of a heavy wooden shaft about three feet long, and an iron head of the same length. The iron was very thin, so that upon striking it easily became bent, and could not be thrown back by the enemy.

223. A new nobility arose from those who had held a curule office. Each such official by law transmitted to his descendants the right to keep upon the walls of his home the wax masks of ancestors, and to have them carried in procession at the funeral of a member of the family. There were only several hundred families of this kind. They were called nobiles, or the senatorial order, because it was from their ranks that the Senate was recruited. To prevent the coming up of new men into this class, a law was passed prescribing that nobody should be eligible for the lowest curule office, the curule aedileship, before he had been quaestor. So if an undesirable person had been quaestor, he could still be kept out when running for curule aedile. This narrow exclusive class of the nobles controlled the government of Rome through the Senate, in spite of democratic assemblies.

224. The Roman Army.—We have seen that the Roman army was organized under the kings into 193 centuries, and the weapons each soldier had to equip himself with were determined. Later, in the wars with the Italians, one armament was prescribed for all classes, except the horsemen and the very poorest citizens. Originally this army fought as the Greeks did, in close array, several men deep. This, too, was gradually given up. The soldiers were so arranged in battle that there was a space between each two men wide enough to allow another to come in. This gave them elbow room for the hand-to-hand fight. When one order of soldiers was tired, another would come up into the spaces between the fighters, while these retreated through the gaps between the newcomers. Thus a constant pressure could be brought to bear upon the enemy.

The soldiers wore a helmet, breastplate, and greaves (to protect the shins), an oblong shield, and a short sword. Each man in the front ranks besides the ordinary equipment had two javelins with thin, long spearheads, to be hurled into the front lines of the enemy. While these were smarting under the wounds, or trying to free themselves from the javelins, the Romans rushed upon them with their short swords. (At the time of which we speak, one order of the Romans also had stout, long lances for thrusting.) With these weapons Rome conquered the world.

The Romans had a certain definite plan for their camps. One Roman camp looked like another. There was a place for the general’s tent and for each of the several classes of soldiers. Every man knew where to find his resting place for the night even in a new camp. The camp was always protected by a rampart.

Discipline was severe. The general could have a soldier scourged or beheaded without a trial.

226. Later Changes in the Military System. — For a long time the army was a citizens’ army. Every Roman was liable to service from the seventeenth to the forty-fifth year of his life. The first innovation, caused by the long wars, consisted in the introduction of pay. When large armies began to be needed mercenary troops were hired, who commonly remained in service for a long time. Thus gradually a class of professional soldiery developed, especially during the wars which we are going to study next. Another important change refers to the appointment of commanders. When a consul was at the head of an army in a far distant land, they often did not take the command from him at the end of his year of office. Instead they gave him the title of proconsul and prolonged his command. — Later on proconsuls were also made governors of certain provinces.

ROMAN SOCIETY ABOUT 300 B.C.

The time from 367 to about 299 B.C. was the noblest period of Roman virtue and vigor. The old distinction between patricians and plebeians was practically gone. A new aristocracy of office grew up and was now in its best age, the “age of service.” The new nobles wanted to rule, but they were also resolved to do their best by the Roman state. It was the Roman people of this age who made Rome the mistress of Italy and started her on her conquest of the world.

226. The People. — The average Roman citizen was still a yeoman farmer and worked his little farm with his own hands and with the help of his wife and children. He raised the ordinary cattle and cultivated wheat and barley on his fields; beans, onions, turnips, and cabbage in his garden; and figs, olives, apples, plums, and pears in his orchard. What he did not need himself he brought to market for sale. In the cities the craftsmen, such as carpenters, shoemakers, dyers, laundrymen, potters, coppersmiths, etc., were organized in gilds for mutual assistance, not for the purpose of raising prices or wages. Once, however, a gild of fluteplayers “struck” for greater privileges. Though there were of course rich and very rich Romans, the cases of extreme poverty do not seem to have been numerous at this time. At any rate, the foundation of the many Roman and Latin colonies served greatly to reduce the number of the very poor. Slavery, too, existed, and was fostered by the brutal custom of selling the populations of conquered towns into bondage. But the slaves of this period were as a rule not treated inhumanly. Historians, think, too, that liberation of slaves was very common, and that many of those who went on Latin colonies were freed slaves (freedmen).

Many of the very rich Romans were still actual farmers, not only owners of large farms. They shared with their family and free and slave workers all the ordinary labors of rural life. They looked down with contempt upon the craftsman in his shop, and the merchant who made money by commerce. This latter occupation, however, later on rose in the esteem of many on account of the huge profits it enabled the merchant to make. As yet the sterling Roman was no merchant.

227. The Roman money is an interesting study. The original coin was an amount of copper which actually represented the value of a sheep. The word for money, pecunia, came from the word for herd, pecus. Later the coin received the round shape, and the law regulated the various pieces exactly as to weight. Silver came into use much later. Those Italian cities which were granted the right of coinage had to conform strictly to the Roman standard.

228. The houses and furniture continued to be very simple. It was a long time before the rich began to possess silver utensils. The principal meal was taken at noon, consisting chiefly of a “porridge” of wheat or barley flour, with pork in the shape of sausage, and bread baked in round flat cakes. Wine, mixed with water, was coming into general use toward the end of this period.

The dress was as simple as the food. The main garment of the men was a short-sleeved woolen shirt, the tunic, reaching to the knees. This was the common dress for the house, workshop, and field. The women wore a long tunic and over it a shorter one, and for the street a blanket-wrap. On all great occasions, when in office or merely attending the assemblies, the Roman citizen wore the toga, the solemn garb of state. It was a white woolen blanket, thrown about the body in graceful folds. It had neither hooks and eyes, nor buttons, nor belt. It had to be held all the time with arm or hand. With some changes in the way of wearing it the Roman toga, which no doubt lent a certain majesty to the appearance, remained in use for a thousand years.

229. Education, imparted to the boys of the rich in private schools by Greek slaves or freedmen, included only the three R’s. There was no poetry, no reading of other literature, no attempt to give the young mind anything like a higher culture. The Roman was exclusively practical. The Twelve Tables were committed to memory, because this knowledge was necessary for the political career and for use in courts. The Romans of this time cared nothing for sciences, and less for belles-lettres, or philosophy. Only after the conquest of Magna Graecia did Greek culture slowly find its way into Roman society. The times of Cicero, however, were still far away.

In architecture, too, the Romans were exclusively practical. The many structures erected at this period, which rightly rouse our admiration, were such as bridges, roads, aqueducts. They made extensive use of the arch. Though some very imperfect sort of arch was here and there employed by the Greeks and even the Babylonians, it is the Romans who fully introduced it into the art of building. The arch is the great contribution of the Romans to the architecture of Europe. (See, however, § 192 and pages 166 and 167.)

230. The Roman ideal was the willingness to sink personal advantages for the public weal. The greatness of the state was his ultimate goal. For this end he was abstemious, obedient to law, self-controlled, but also rapacious and cruel. He practiced generosity toward a beaten foe only when it was demanded by political cunning. Otherwise the noblest adversary could count only on the most merciless punishment.