The following is an excerpt (pages 287-311) from Ancient and Medieval History (1946) by Francis S. Betten, S.J. Although some information may be outdated, the Catholic historical perspective it provides remains pertinent. Use the link at the bottom of post to read the previous/following pages. Use the Search box above to find specific topics or browse using the Resources tab above.

BOOK TWO

MEDIEVAL HISTORY

PART SIX: FROM THE ANCIENT ROMAN EMPIRE TO THE HOLY ROMAN EMPIRE (400 A.D. to 800 A.D.)

The Middle Ages are the time during which the religion of Jesus Christ became and remained the dominant faith of all the states of Europe. The old unity of the Roman Empire disappeared. New nations of a different stamp were to form the new states. They destroyed much of the civilization that existed. But the Church became their educator and taught them the very civilization they had done so much to eradicate.

The old Roman Empire was to be replaced eventually by the Holy Roman Empire with less power but higher aims and purposes. This transition from the old to the new Empire will cover an epoch of four hundred years.

CHAPTER XXIX

THE MIGRATION OF NATIONS

CONDITIONS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE ABOUT THE YEAR 400 A.D.

382. Decrease of the Population. — The three quarters of a century after Constantine the Great had been marked by a fair degree of outward prosperity. But the secret forces that were sapping the strength of society continued to be at work. Christianity, while increasing in numbers and interior vigor, had not yet had time enough to penetrate all the strata of the population, to create a new race with better habits, and to stop the inveterate immorality with its sad consequences. The numbers of inhabitants continued to decrease (§ 352).

383. Lack of Money. — Strange as it may seem, the output of the gold and silver mines was no longer what it had been before, and as a consequence the coinage of money could not be kept up. Besides, much money went abroad to pay for the luxuries imported from foreign countries, especially India. The rich, too, continued to have precious jewelry, statues, and other articles made, thus tying up the gold and silver that might have been used for money. Things became so bad that the emperors resorted to the desperate means of mixing baser metals with the gold and silver of the coins, a measure which naturally tended to demoralize commerce. In many ways society returned to barter. Even imperial officials had to accept part of their salaries in the shape of robes, horses, wheat, etc.

384. Taxes became crushing, partly because people found it more and more difficult to get the money for payment, partly because the number of taxpayers dwindled down with the population and partly on account of the creation of ever new offices in the government machinery. Perhaps the worst feature was that the richest men in the Empire had succeeded in being entirely or partly freed from taxes, so that the burden weighed all the more heavily upon the less rich and the poor. The writers of the period tell us that people actually fled across the boundary to the barbarians to escape the vexations of the tax collector. And yet though growing heavier to the citizens as time went on, taxation yielded less and less revenue. Taxes, too, in particular the heavy taxes on farming, were largely paid in kind. The grain served, among other things, to feed the rabble in the large cities, as Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria.

385. Agriculture, and the Lot of the Peasants. — Excepting some half-hearted measures, the government had given up making any attempt to preserve or restore the free peasant population in the Empire. In the course of time the small farms of free yeomen disappeared in the provinces, as they had at an earlier date in Italy, and became incorporated into latifundia (§ 259). Countless cultivators abandoned their

farms, because they saw they could not pay the taxes. The great landowners, too, found it increasingly difficult to have their enormous estates taken care of. Under these circumstances, the government made a more extensive use of an expedient often resorted to under previous reigns. After successful wars it surrendered barbarian captives in large numbers to the great landlords, not as slaves but as serfs. The serf received each his own diminutive farm for which he paid rent in produce, or labor, or money. As long as he fulfilled his duties, he could not legally be evicted from his lot. Serfdom is a sort of half-slavery. The result was that the free farmers found it still more difficult to make their living. They sank into serfdom, while, on the other hand, the slaves in many cases rose to that condition. In the end, practically all the tillers of the soil were serfs. Unfortunately the tax collector came upon the serfs also, and demanded a tax directly to the state, besides their dues to the lord of the land.

386. Lack of Interest in the Common Welfare. — The cities and towns groaned under the heavy weight of the taxes. The government had made the magistrates personally responsible for the taxes due by the whole town. These honorable offices, once eagerly coveted by the richer citizens, were now dreaded, and had to be imposed almost by force. At the same time the greed of the merchants had raised the prices of the most necessary things to fabulous heights, so that the poorer people found it extremely difficult to make ends meet. Hence civic pride, local patriotism, and the interest formerly taken by all in the welfare and greatness of the common town waned and were giving way to a deplorable apathy.

The same apathy took hold of wide circles concerning the welfare of the Empire at large. The people wanted the Empire, of course. They knew they could not exist without it. But was it not the emperor’s concern to look after its interests and defend it with his troops? They themselves could do nothing. For several centuries the emperor had taken upon himself the duty and the privilege to think of its needs and to find ways and means to remedy them. The people were forced, and were by this time accustomed, to leave that matter entirely in his hands. Meantime it became more and more difficult to fill the gaps in the legions, despite the admission of barbarians into the ranks.

387. Yet these conditions must not be exaggerated. The

Empire remained the home of the best civilization that mankind had ever reached. Its cities, though slipping, harbored a highly refined society. The government, with diminishing efficiency, maintained law and order — the systematic enlargement of the network of roads was carried on even to a much later date — and the well-organized schools continued to promote knowledge of all kinds, especially the literary arts. And although architecture, sculpture, painting, and the higher branches of handicraft suffered from a decay in general taste and were inferior even in mechanical execution, yet at this time also notable works continued to be produced.

Moreover, it would be too much to say that the continuous decay fully explains the cessation of the Empire in the west. It helps to explain it to a very large degree. The character of the nations who brought it about is another cause. But even if all is duly considered, the fall of Rome’s power remains one of the unsolved riddles of history.

THE NATIONS BEYOND THE FRONTIER

388. The Teutons. — As set forth in § 275, the first Germanic or Teutonic nations named in Roman history are the Cimbri and Teutones, who were defeated by Marius. An invasion of Ariovistus, King of the Suevi, was averted by Caesar (§ 291). Several other Germanic tribes have been mentioned in the course of the history of the emperors (§§ 374, 375). We saw how Augustus failed in his attempt to push the Roman frontiers beyond the Rhine. Some Germanic tribes tried to force their way into the Empire, but were beaten back.

From these few facts the student will have gathered that the Teutons were by no means one political unit. The number of the tribes into which they were divided was very large. They were often at war with one another, or allied with the Romans or some other power against their kinsmen of other tribes. But they had common qualities. Each tribe could understand the language of the others. The principal traits of their religion were common to all, and their social and political institutions were more or less the same. These tribes had been roaming for a long time in the countries north of the Danube and the Black Sea from the Rhine to the Caspian Sea, each settling for some time, twenty or more years, some as long as a century, in one place.

389. They possessed some primitive civilization. They dwelt in huts plainly constructed of wood and clay or the bark of trees. Agriculture, little encouraged by the climate, was left almost wholly to the women, the old men, and the slaves. A sort of commerce existed between them and the civilized nations in the south, with whom they exchanged amber and other mothers, sisters, and daughters much more than their own captivity. In products of the countries in which they lived for weapons and jewelry and household articles. For lack of suitable material, handicraft, with the exception perhaps of the armorer’s trade, was little developed.

The Roman writer Tacitus highly praised their family life, and the reverence they had for women. The men dreaded the captivity of their wives, war they would come and show them their wounds, to receive their words of commendation, which they highly valued.

Their religion was a rude -polytheism. They had no temples but worshiped their gods on hilltops, at springs, and in forests. Woden (Wotan) was their highest god, and from him the noble families claimed descent. Thor or Donar, whose hurling hammer caused thunder, was the god of storms; Freya, the goddess of joy and fruitfulness. The Germanic gods still live in our names for the days of the week. Woden’s day, Thor’s day, Freya’s day, are easily recognized. Tuesday and Saturday take their names from two minor gods, Tiw and Saetere; the remaining two days are those of the sun and the moon.

390. Forms of Teutonic Government. — The members of a tribe lived scattered in several villages, each of which had its assembly and its chief. There was also a general assembly of the whole tribe. Many tribes elected kings from the members of certain families. Other tribes had no such common head in peace time, but created dukes as leaders in war. The Teutons had taken over a peculiar institution from the Celts. Powerful chiefs surrounded themselves with hands of companions who lived in the chief’s household, fought his battles, and were ready to give their lives for his safety. To desert him in danger or leave his body to the foe was a lifelong disgrace. The chief in turn was dishonored if he failed to do his utmost for the safety of his companions.

The Book of Kells is an Irish manuscript containing the four Gospels and some minor writings. It dates from about 700 A.D. It was long preserved in the cathedral of Kells, and is now in the library of Trinity College (Protestant), Dublin. “No words can describe the beauty and the extreme splendor of the richly colored initial letters” (Catholic Encyclopedia). This page shows the monogram of Christ (see illustration on page 235). The X appears above , three of its lines being elegantly curved, and the fourth lengthened downward. The P and an additional I are seen below. (Ornamentation of manuscripts and the goldsmith’s art had reached a high perfection in Ireland.)

391. Non-Teutonic Races. — Though in the next chapter we have to deal with the Teutonic nations who left their homes and found other habitations, we may look ahead and state that a large part of the places abandoned by them were occupied by Slavs, the race to which belong the Bohemians, Poles, Slavonians and others. We shall also have to mention the Magyars (Hungarians proper), who, though in color of skin and general build like the rest of present-day Europeans, speak a language which is akin to that of the Mongolians (Chinese and Japanese). These races found their dwelling places centuries later. But in immediate contact with the Germans in the far east, north of the Black Sea, there appeared the Huns, a fierce Mongolian race of horsemen, who by their attack upon the Goths started the Migration of Nations.

The greater part of the Celtic race lived under Roman sway in northern Italy, Gaul, northern Spain, and the south of Britain. These Celts had become thoroughly Romanized, had given up their own languages and adopted that of Rome. The Gallo Romans (in present France) possessed excellent schools, which by many were preferred to those in other countries. Historians are of opinion that the transmission of Roman civilization to the new nations was the special task of the Gallo-Romans. Two small Celtic nations, however, had remained outside the empire, namely, the inhabitants of Scotland and Ireland.

THE MIGRATION OF NATIONS

392. Ireland was ruled by native chieftains and kings, called “ Righs,” under an overking, styled “ Ard-Righ,” who resided at Tara. An elaborate system of laws, controlled by a professional class of jurists, the brehons, regulated all conditions and relations between high and low. Prose and poetry of all shapes, the drama alone excepted, were cultivated by professional writers. Education was cast into a very definite system which provided for a number of graded courses. Agriculture, especially cattle raising, was the main occupation. Foreign trade was not neglected. Life was exceedingly simple. All buildings, even the abodes of the chieftains, were of wood. But although Irish civilization lacked exterior brilliancy, the Irish were a really cultured nation. In 432 St. Patrick undertook their conversion. He obtained the consent of the Ard-Righ for his work. At his death, after a whole life of apostolic labors, of prayer and penance, Ireland was practically Christian. St. Patrick thoroughly Christianized both the Brehon Law and all social usages. The result was an intensely Christian nation, whose religious earnestness showed itself in the rise of numerous and well-peopled monasteries.

THE MIGRATION OF NATIONS

393. Character of the Migration of Nations. — In 400 A.D. or thereabouts began the victorious entry of the Teutonic nations into the Roman world. They defeated the Roman armies and set up their own kingdoms in the midst of the Roman population. Still they had no thought of uprooting the Empire as such. The mighty fabric with its wonderful methods of government, its imposing cities and majestic buildings stood too high in the opinion of these open-hearted children of nature. They had, moreover, made their own the conviction of the Romans that the Empire was an absolute necessity for the welfare of mankind and consequently neither should nor could be destroyed. The fiction prevailed that the Teutonic kings of the states founded on Roman soil had their power from the emperor, though in practice they cared little for his supremacy. In opposition to the invaders the old population was referred to as “Romans,” whether they were Italians, or Gauls, or Africans.

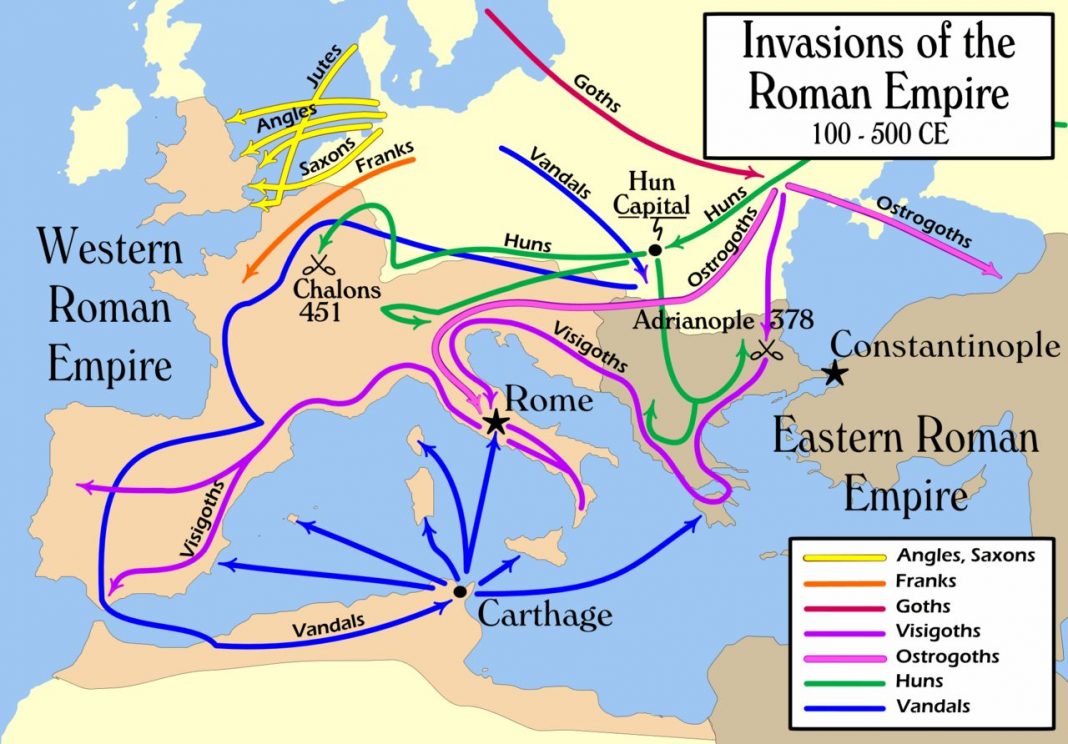

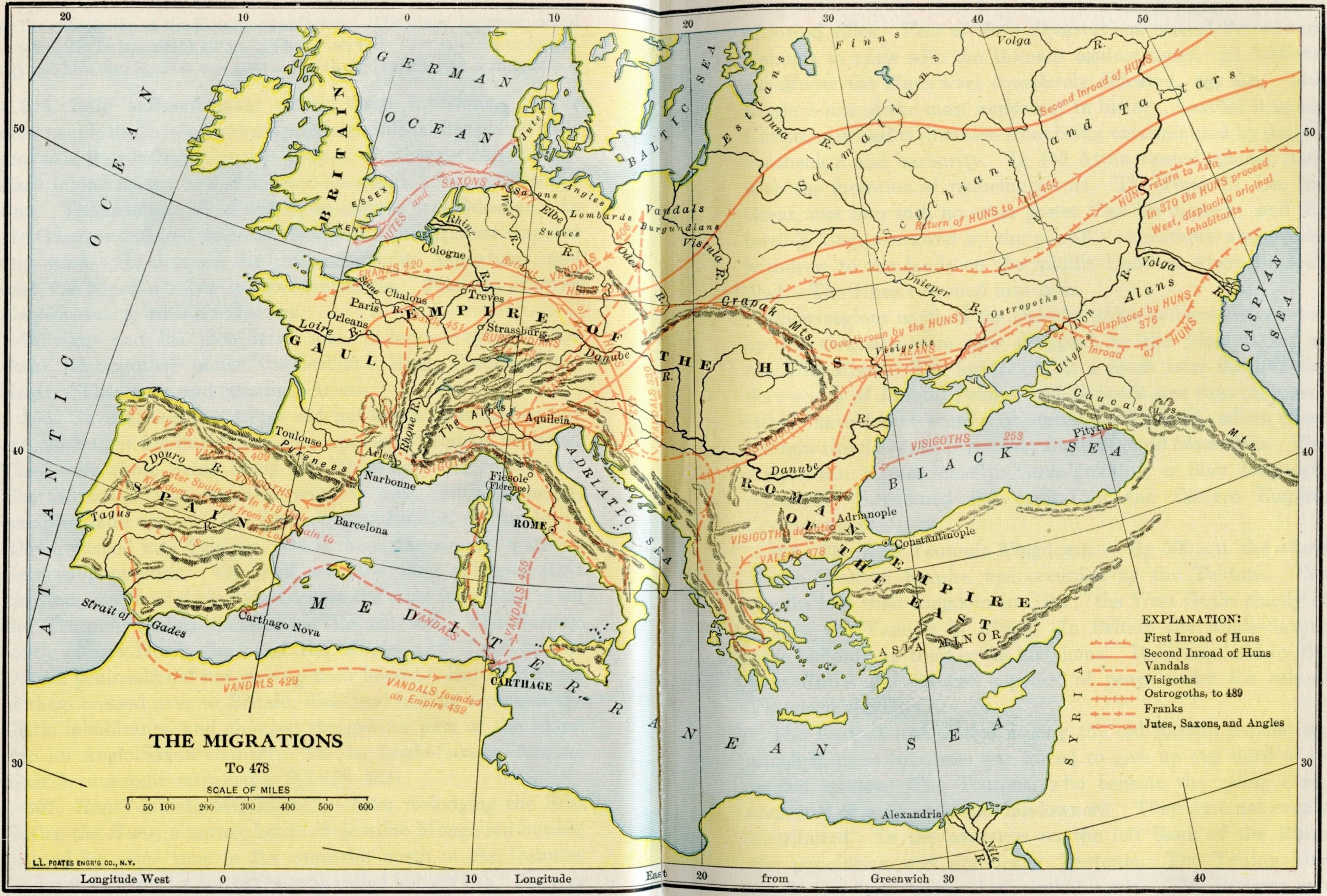

394. The Migrations of the Teutons. — In 375 the Huns (§ 397) crossed the Volga and attacked the East Goths who lived north of the Black Sea. These in turn forced the West Goths out of their seats. The latter, with their wives and children, fled southwest to the Danube, carrying their goods, as all the wandering nations did, in long trains of wooden carts. They petitioned the Emperor Valens at Constantinople to give them lands south of the river (§ 375). After they had been settled there the greed of imperial agents who were to furnish them food drove them into rebellion. They defeated and killed the Emperor and obtained better terms, but rose again after twenty years for the same reason. They now roamed for several years, plundering and devastating, through Greece, Dalmatia, Italy, and Gaul, settled on both sides of the Pyrenees, and founded the West Gothic kingdom, which included the south of Gaul and practically all Spain. The most important event during these wanderings was the three days’ sack of Rome, in 410, the news of which struck the civilized world like a thunderbolt. The West Goths were Arians (§ 379). Only after their conversion to Catholicism, in 585 A.D., did they fuse with the “Roman” population.

The Vandals, after a long migration and a temporary stay in Spain, settled in North Africa. In the year 455 A.D. their warriors sailed over to Italy and inflicted upon the helpless capital of the world a second plundering much more frightful than the first. The Vandals ever remained Arians and fiercely persecuted the Catholic population. The Burgundians took possession of the Rhone valley. They were Arians, but eventually became Catholics.

The Teutonic kings forced from the emperor some Roman title, either military or governmental. By granting it the helpless emperor saved the appearance of his actual overlordship, and the kings acquired a claim to the submission of the Roman population. The kings, however, acted as perfectly independent rulers. They “served” the emperor or fought against him and against one another as their own interest demanded.

395. Italy suffered most under these invasions. People after people broke into the unhappy peninsula, either to find their graves in it or to leave it again in quest of other dwelling places. Each inroad caused loss of life and devastation beyond description. The chieftain of one of these nations was Odoaker. In 476 Odoaker declared that the West needed no separate emperor any more. He deposed the young Romulus Augustulus, and sent the imperial robes to Constantinople. Thus the Western Empire came to an inglorious end.

Odoaker and his men were soon dislodged by the East Goths (Ostrogoths) under the brilliant King Theodoric the Great. They were and remained Arians.

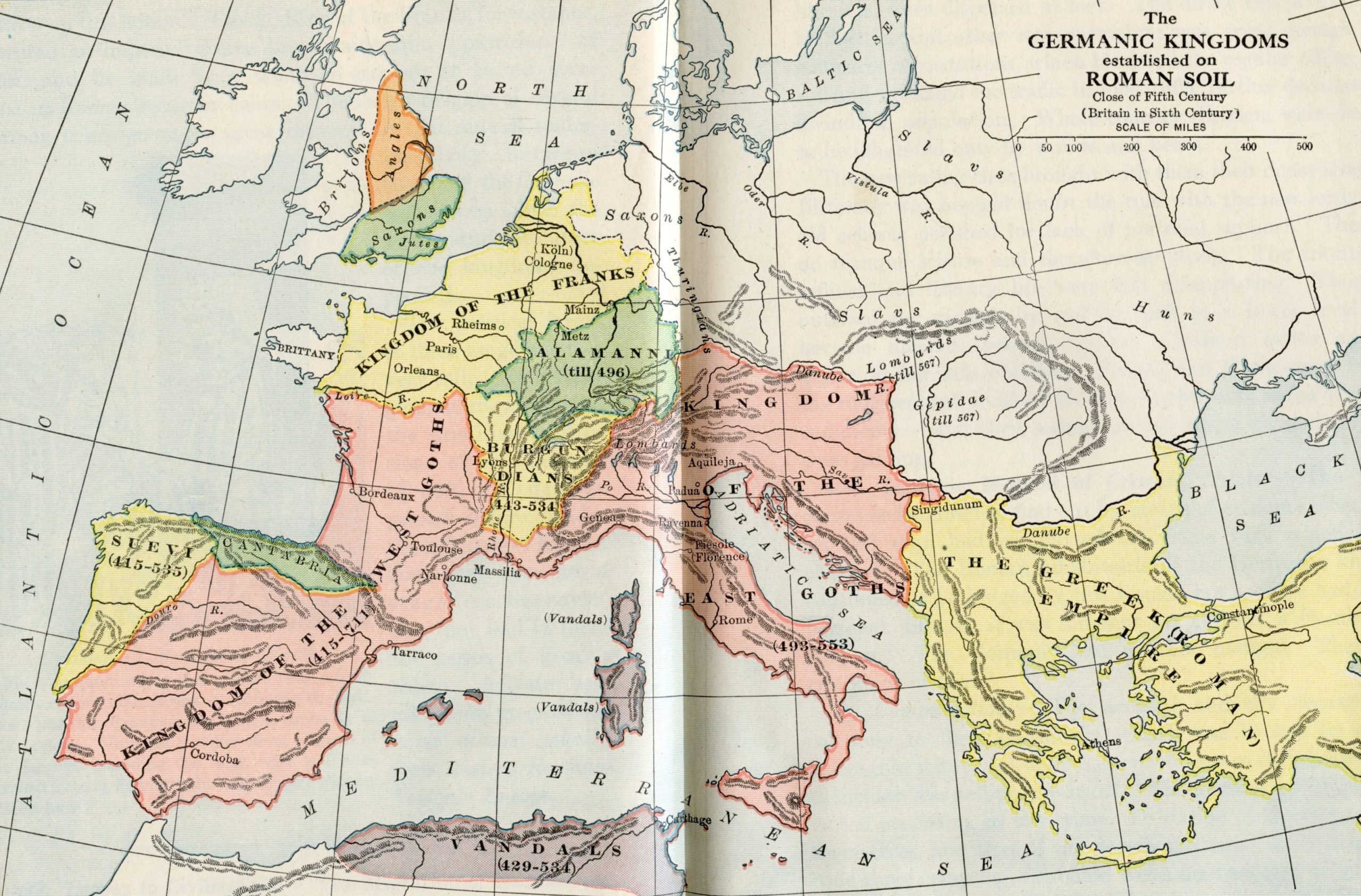

396. Several German tribes did not leave their homes but extended their habitations at the expense of Roman territory. They were those living along the Rhine and the North Sea. The Alemanni, who dwelt in what is now South Germany, occupied land west of the Rhine. The Franks, on the lower Rhine, pushed into Belgium, where there was already a strong German population. We shall see how they enlarged their kingdom, and how their state became the most important of all the Teutonic realms founded on Roman soil. The Saxons, south of the North Sea, and the Angles and Jutes on the Danish peninsula did not give up their homes. But multitudes of them crossed over to Britain, dislodged in long struggles the Celtic inhabitants, and changed the greater part of the island into an Anglo-Saxon country. To the Anglo-Saxons, too, we must devote some extra pages (§§ 458-463).

397. Non-Teutonic Migrations. — After dislodging the East Goths, the Huns, a savage brood of genuine Mongolian hordes, roamed for some time in the countries north of the Danube. Under their fierce leader Attila, who called himself the “Scourge of God,” they invaded northern Gaul with an innumerable host of forced allies. Fear of their devastations caused the western Teutons to unite with the Romans against them. At Chalons-sur-Marne the Huns were completely defeated, 451 A.D. This battle is one of the most important in history, because it saved Christianity and civilization from being exterminated by Asiatic heathenism and barbarity. In 452 Attila turned against Italy with the intention of reducing Rome. The Pope, St. Leo the Great, met him with no other power than his dignity; and the terrible king, overawed by the pontiff’s appearance and words, withdrew to the lands on the middle Danube, where he soon died. The Huns returned into Asia.

Those regions north of the Danube which had been evacuated by the Germans were now occupied by the Slavs as far as the Elbe River. The formation, at a much later date, of the Slav states of Russia, Poland, and Bohemia was thus prepared. Other Slavs found their way across the Danube, where there are now the Serbians, Croatians, Bosnians, and Slavonians. The Bulgarians, a race chiefly Turanian with a Slav language, repeatedly threatened the capital of the Eastern Empire, Constantinople.

398. The New Teutonic Kingdoms. — By 500 A.D. the whole of the Western Empire was occupied by the Teutons. The Franks had their kingdom in Gaul; the West Goths chiefly in Spain; the Vandals in Africa. In Britain the Anglo-Saxons were building up their seven kingdoms. Italy was held by the East Goths and enjoyed a period of peace under the rule of Theodoric the Great.

The Teutons had settled among the old Roman population, which in most countries was forced to give up one third of its landed estates. The Teutons, who became the ruling class, consisted of large and small landowners. They were not evenly distributed. In the countries on the left bank of the Rhine the population was practically Teutonic. The Teuton king ruled over both parts of the inhabitants. The Romans saw in him a representative of the emperor, and the king was careful to keep up this fiction. Clovis, King of the Franks, for instance, procured an imperial decree proclaiming him “Patrician” of Gaul, and he made it a point to appear at stated occasions in Roman consular robes. The Arian religion of several German tribes proved a great obstacle to that mutual understanding between them and the Catholic Romans on which the welfare and the future of the kingdoms depended.

The political fabric of these kingdoms was very rude. In the beginning they retained the primitive institutions of the Teutons (§ 390). Centuries passed before, under the influence of Roman law, they rose to a stage less barbaric. But they had in them the germs of greater Teutonic Europe.

CIVILIZATION AND CHRISTIANITY

399. Losses to Civilization. — The Migration of Nations was the most terrible catastrophe that ever befell a great civilized society. Many of the most flourishing cities were destroyed, or had greatly suffered by sackings. The treasures of art, including libraries, were dispersed or lost. The direct loss of life caused by battles and other war operations was great enough. The countless devastations, which hindered the regular tilling of the soil and deranged the traffic in foodstuffs, further decimated the dwindling population. Whole country districts were deserted, to be inhabited only by wolves and bears.

The new ruling class brought with them their dense ignorance. Illiteracy was beyond doubt the rule with the new lords. The old schools perished for lack of material support. There was no tranquil leisure and therefore no study. The traditions of refined and literary life were fast disappearing. Those who outlived the ravages by and by sank to a lower level. Life became meaner, poorer, harder. Civilized tastes and arts began to fall into oblivion. Franks and Goths were learning the rudiments of civilized life; the Latins were losing all but the rudiments — and they seemed to lose faster than the Teutons were gaining.

400. Teutonic Method of Criminal Trials. — The Roman courts endeavored to find out by means of evidence whether the accused man had committed the crime with which he was charged. The Roman inhabitants of the Germanic kingdoms continued to be judged by this Roman law. (Law had become personal, that, is, it was different for a Goth, a Frank, and a Roman.) The Germans had another method. There were two kinds of trial:

By Compurgation. — The accused and the accuser swore solemnly to their statements. Each was backed by compurgators (not witnesses), that is, men who swore they believed that their man was telling the truth. The number of compurgators varied according to the crime, the station of the compurgators themselves, and that of the person accused. According to one code three compurgators could free a man accused of murdering a serf; it took eleven if the murdered man was a noble.

By Ordeal. — The ordeal was based on the erroneous assumption that God would rather work an evident miracle than allow an innocent man to be punished. To clear himself of a charge, the accused would, for instance, offer to plunge his arm into boiling water, or carry red-hot iron a certain distance, or walk over glowing plowshares. If his flesh was found uninjured when examined some days later, or if the wound was healing in a natural manner, he was declared not guilty. The idea had struck so deep in the popular mind, that the Church, though never approving of it, took it into her own hands. To prevent violence and fraud, she surrounded the proceedings with impressive sacred ceremonies. It required several centuries to do away finally with the barbarous custom. (Such tests were sometimes made by deputy; hence our phrase, “to go through fire and water” for a friend).

The nobles preferred the ordeal of the single combat, supposing that God would assist the arms of the innocent party. A relic of this ordeal is the duel, which happily is becoming rarer in our times. The Church inflicts the severest ecclesiastical penalties on duelists.

Penalties for crimes, too, were different. Offenses were atoned for by money payments. Practically all crimes had a money penalty, varying from a small amount for cutting off the joint of the little finger to the wer-geld or payment for a man’s life. The wer-geld varied with the rank of the victim.

401. What became of the Latin language? There had always been differences in the way Latin was spoken in the several provinces of the Empire. When the unity of the Empire was gone and the schools ruined, the old Latin assumed more and more distinct characters in the various regions. In the course of several centuries each province developed its own speech. Thus gradually arose the languages which we now call French, Spanish, and Italian. In the districts near the left bank of the Rhine the German language completely dislodged whatever there had been of Latin. But Latin remained in use among the clergy of all countries, though at times many even of these knew it

imperfectly.

402. Roman civilization was not uprooted entirely. The conquests were for the most part made by numbers too small to change the character of the population, and unable to dislodge all the traditions of the former refined life. Many of the newcomers, too, though semibarbarians, were open-minded enough recognize the cultural superiority of the Romans. In this way the Teutons in Gaul were slowly civilized by the Gallo-Roman population, which thus indirectly became the link between the old and the new civilization. Moreover, the kings and other Teutonic lords drew their confidential advisers preferably from the educated classes of the Romans, especially the bishops and the clergy. By these they with their retainers were made acquainted with the tastes and customs of civilized life, and with better methods of government. Finally since the invaders settled chiefly in the country, the cities and towns as far as they survived preserved some features of the old culture and the old handicrafts. They continued governing themselves, even with more liberty after the imperial oppressions had ceased, and so prepared the flourishing town and city life of the later Middle Ages. Through these different agencies much of the old civilization, which at the time seemed ruined, was sooner or later recovered in the Teutonic kingdoms, so that “ nearly every achievement of the Greeks and Romans in thought, science, law, and the practical arts is now a part of our civilization.”

403. It was above all the Church that saved civilization and

reared the new peoples of Europe. By the time that the German invaders began to pour into the Roman Empire, all its provinces were practically Christianized. There was everywhere a well-established hierarchy. Bishops watched over the spiritual welfare of the faithful, without neglecting temporal interests. True, the settling of the rude barbarians among the Christians, the concomitant weakening of public order and safety, the loss of life and the decline of material as well as intellectual civilization had a deplorable effect on morals and discipline. In Gaul, with which we are particularly concerned, the Teutonic kings, though Catholic, often led almost pagan lives. The conversion of the newcomers proceeded slowly, nor must it be imagined that the newly converted Teutons and their first descendants were at once, and without exception, exemplary Christians. This reacted on the old population. Many of the clergy, some even among the hierarchy, sorely lacked the purity of morals and singleness of purpose required by their exalted vocation.

All this notwithstanding, the Church was the salt that kept the world from complete corruption, and preserved the means for it to rise again to a higher level of civilization. The Church always demanded a certain degree of education in her ministers and provided for some kind of schools. Even in the most troubled periods there were priests, monks, bishops, and lay persons of both sexes who were more than ordinarily inspired with zeal for true virtue and righteousness in themselves and their fellow men. The Church protected the weak and stood for peace, education, industry, and right living. “She was the chief force that made life tolerable for myriads of men and women in those dark ages.” She also preserved many of the forms and habits of the Roman law and by her advice and example improved the rude methods of the new rulers. “Only to the strenuous exertions of Christians and the spiritual impulse maintained among mankind by the new religion do we owe it that these ages found any pleasure in the classics of antiquity and did not allow them to be irrevocably lost.”

404. The Papacy. — No Christian institution exerted a more powerful influence for good than the papacy. The popes ever kept their eye on the needs of the world at large. It was they who sent out the great missionaries to the new nations. The most prominent pope of this period of storm and stress is no doubt St. Gregory the Great, who presided over the welfare of the Church 590-604. He had the consolation of welcoming into the true fold the Arian nations of the West Goths and the Lombards, and he sent St. Augustine with his monks to convert the Anglo-Saxons from paganism.

405. Irish Influence. — The destructive waves of the Migration of Nations did not reach Ireland, where with Christianity the Latin and Greek classics had found a home and countless enthusiastic devotees in the old and new schools. Thus the far-off island helped to perpetuate Christian and Roman civilization. Irish monks began to emigrate to the continent, where they settled among the new nations, and by their example and preaching promoted both the purity of Christian morals and love of classical scholarship. St. Columba (Columbkille) became the Apostle of Scotland, where he established the great island monastery of Iona as a center and headquarters of missionary labors. St. Columbanus founded monasteries in and near the Alps among the Franks and Burgundians, and with his disciples gave a new impetus to the Christianization of the Alemanni. Meanwhile the renown of the schools in Ireland was so great that eager students flocked to it from other countries. In the stormy period of the Migration of Nations Ireland was like a university for Europe.

MONASTICISM

406. Origin of Monasticism. — There have never been wanting in the Church those who desired to accept the invitation addressed by Christ to the rich young man: “ If thou wilt be perfect, go, sell all thou hast and give it to the poor, and come, follow me ” (Matt. XIX, 21). But the conditions of the first centuries did not permit the establishment of convents and other religious houses as we know them now. In the third century many Christians of both sexes withdrew into deserts and forests, where in solitary huts or caves they lived exclusively for God and the welfare of their souls. St. Paul of Egypt is considered the first to have chosen this life of the hermits. But many preferred to dwell in communities where they could have the advantage of mutual encouragement and the guidance of a superior. St. Anthony of Egypt began this kind of religious life.

407. Spread of Monasticism. — Both modes of religious life spread rapidly from Egypt, where they were extensively practiced, over the Orient. St. Basil the Great later on became the lawgiver for the monasteries — this was the name given to these institutions — of the whole East. By the end of the fourth century monasteries of monks and nuns, that is, men and women living in such religious communities, existed also in all parts of Christian Europe. In the first half of the sixth century St. Benedict (died 543), an Italian, wrote his famous “Benedictine Rule,” noted for practical wisdom and moderation. In the course of several centuries this rule was adopted by all the existing convents (monasteries) of western Europe. Each house, called an “abbey,” was ruled by an abbot or abbess. The abbeys had, however, no common general superior, the unity of the order being kept up solely by the observance of the same regulations.

408. The inmates of the monasteries lived a life of perpetual poverty, chastity, and obedience. Self-sanctification was their chief object and the source from which sprang all their achievements in the promotion of civilization and Christianity. Hence a great part of their time was given to exercises of piety and penance. They would settle in some uncultivated spot, and by the work of their hands change it into well-tilled fields and gardens. By word and example they taught the dignity of manual labor, encouraged agriculture, and often showed the dwellers-around better methods for working their fields. They also protected the poor against the rich and powerful, because commonly the rude invaders respected the peaceful and helpless inhabitants of the cloister. Then, too, the monks lovingly copied books, both spiritual and profane (page 2). It was they that preserved the treasures of the classical literature of Rome and Greece. For centuries the convents were the almshouses, inns, hospitals, and schools of Christendom.

The life of the nuns was similar. Exercises of piety, manual labor in their gardens, the instruction of girls in their schools, the copying of books, and needlework for the benefit of the poor and the service of the altar were their occupations. Frequently they provided, by their own labor and by collecting alms, for the necessities of the missionaries in far-off countries.

409. The monks for the most part were laymen. Priestly ministrations were not the original and never the sole purpose of the monasteries of those days. Still, not only did the monks and nuns preach a most powerful sermon by their example, but the results of the activity of their missionaries are almost incredible (see §§ 405, 426). From the earliest period men and women prominent for rank and wealth entered the convents to spend their lives in piety, humility, and penance.

410. Religious poverty is not pauperism. It consists essentially in this, that the individual depends upon the permission of his superior for the use of all things. Actual want or misery, often experienced by the first members of monastic institutions, would in the long run rather have a detrimental effect upon the observance of religious discipline. In those times it was understood that the property held by each institution should at least enable the members to support themselves frugally by their own labor. Many abbeys, however, grew very rich, chiefly because their labor had increased the value of their once barren lands. This did not constitute a real danger to discipline as long as the monastic regulations were well observed. It was different when men who were not imbued with the right spirit obtained the position of abbots. Such persons, mostly intruded by secular interference, administered the property for their own benefit, and cared nothing for the enforcement of the rules. Yet, it is granted by all historians that in spite of the cases of corruption which at times took hold of these abodes of sanctity the monks and nuns have rendered inestimable services to mankind, and that our present civilization is largely based upon the fruits of their pious and persevering labor.

THE EASTERN EMPIRE

411. The Eastern Empire, too, suffered from the invasions. Several of its northern provinces, next to the Danube, were lost, but its capital, Constantinople, was never conquered. The provinces bordering on the Aegean Sea and those in Asia remained practically unmolested. Though they continued to suffer from the general decay referred to before (§ 382 ff.) they largely retained their ancient culture, the inheritance of centuries of refinement, elevated by the influence of Christianity. Constantinople above all was the home of civilization. It was the most splendid city in the world. It possessed beautiful parks, and its well-paved streets were lighted by night. Its brilliant churches and imperial palaces were the marvel of the universe. Hospitals and orphan asylums took care of the poor. It was also the center of trade and manufacture. Its silks, jewelry, glazed pottery, weapons, and mosaics found their way into foreign lands, including the now semi-cultured West. The population numbered about a million. Unfortunately the despotism of its rulers had left little to the initiative of the citizens. It had lessened and was still lessening more and more the interest which private citizens should take in the general welfare, and their ability to realize and meet common dangers. Worse than this, the constant interference of the emperors in Church affairs, even in matters of doctrine, and the fact that the appointment of all the bishops had been usurped by a secular authority, which was often prompted by merely political reasons, tended to reduce the Church, the mightiest factor in civilization, into slavish subjection and unproductive stagnancy.

The Empire had, however, several strong emperors and one excellent empress, St. Pulcheria. We must especially mention Justinian I, called the Great, whose reign lasted nearly forty years, from 527 to 565. His chief work was the codification of the Roman law and successful wars against Teutonic states in the West.

412. Codification of Roman Law. — The Roman laws regulating the relation of citizens to the government and to one another were not the work of one man. They had been issued by and by, in the course of several centuries, just as they were needed. Several emperors had had them “codified,” that is, they had them gathered in one “code ” or law book, putting together all those laws which were bearing on one subject. Justinian set a committee of learned men to codifying them anew. The “Code of Justinian ” thus produced was wonderfully comprehensive clear, and orderly, so much so that later centuries found little to improve on it. When the Teutonic kingdoms began to codify their own unwritten laws, the Roman law furnished the foundation, and many of its enactments passed over into the laws of the new states. Without the knowledge of this code none, perhaps, of our modern codes can be fully understood, the most independent being those of England and the United States.

This excellent system of laws is not, however, without serious shortcomings. It does not sufficiently recognize the value and dignity of labor. Moreover, it makes the emperor the sole source of all rights, and thus tends to increase the power of the princes unduly. The excesses of some individual rulers of the Middle Ages are directly traceable to the unreserved adoption of Justinian’s principles.

Justinian was not an efficient financial administrator. Taxes rose to an enormous height, and yet his treasury was always empty. His absolute and arbitrary power extended to Church matters also. He meddled in purely dogmatical questions, and still more in the discipline of the Church, and kept Pope Vigilius for six years imprisoned in Constantinople.

413. Justinian’s Wars against the Teutons. — When Justinian came to the throne, the Vandals had their kingdom in northern Africa, and the East Goths controlled all Italy. The great general Belisarius defeated the Vandals and made northern Africa again an imperial province, which was ruled by a governor called “exarch.” Then Belisarius and Narses, in a twenty years’ war, drove the East Goths out of Italy, and that country, too, became a Roman province, the exarch residing in Ravenna. But in 568, three years after Justinian’s death, the Lombards, a Teutonic nation, half pagan, half Arian, swarmed into the peninsula, and conquered it with the exception of the southern part and a little district in the center with the capitals of Ravenna and Rome. Thus Italy was divided between the newcomers and the Empire. That little section in the center, however, was destined to play an important part in the history of the Christian world.

This inroad of the Lombards into Italy, in 568, is the last of the great migrations of the Teutons, which had begun in 375 with the admission of the Visigoths into the Empire (§ 394). Franks, Lombards, Visigoths, and Anglo-Saxons had divided among them the soil of what was formerly Roman Europe.

However, the idea of the Roman Empire as the one universal government of the world (§ 371) continued in the minds of men until, after three hundred years, this Empire was revived in the West by the imperial coronation of Charlemagne.

RISE OF THE FRANKS

414. King Clovis. — We have seen how the Franks, a confederacy of German tribes living on the banks of the lower Rhine, extended their habitations into Gaul (§ 396) and united that entire country together with a wide territory on the right bank of the upper Rhine into one kingdom. This was chiefly the work of one man, King Clovis (Chlodwig, Ludwig, Louis, Aloysius), of the family called Merowingians from the name of their ancestor Merowig. King Clovis was the founder of Frankish greatness. When at the age of fifteen years he entered upon his career of aggrandizement, he was still a pagan and a real barbarian, though not without some noble traits of character and a shrewd mind. He had inherited from his father a leaning toward Christianity. His wife, St. Clotilda, a Burgundian princess, was a devout Catholic. The decisive battle against the Alemanni, in 496 A.D., which tradition places at Zülpich, became the occasion of his conversion. In the crisis of the battle, Clovis vowed to serve the God of Clotilda if he gained the victory. His prayer being granted, the king and three thousand of his warriors were baptized.

415. The baptism of the Frankish king was a momentous event. By it that nation which was to play the most important part in the political history of the future entered into a union with the Church, the champion of true righteousness and civilization. It brought to Clovis the good will and confidence of the Catholic population of Gaul and the hearty support of the Church authorities, including the papacy. While the rule of Arian kings was hated, the Frankish kingdom enjoyed the blessings of perfect religious unity. Nor did Clovis neglect to reconcile the political feelings of the Celto-Roman population (§ 391).

416. Clovis meant to rule as a Christian king. He placed the Celto-Roman population on the same footing as his Franks, and left the bishops undisturbed in the execution of their office. He ever preserved an unswerving devotion to the saintly Clotilda, whose example and encouragement he followed in the practice of a far-reaching charity toward the unfortunate and great liberality toward ecclesiastical institutions. At the same time, however, acts of violence and cruel revenge and the charge of broken pledges disfigure the records of his political career. The nation, like the rulers, did not at once become thoroughly Christianized. Only gradually did the Church succeed in taming its wild passions.

417. The Frankish Kingdom. — Before his conversion Clovis conquered a territory in the northwest of Gaul which till then had remained under the sway of a Roman governor. He now drove the Arian Visigoths out of the southwest of Gaul, and was received as a deliverer by the Catholic population. His sons completed the conquest of Burgundy. They added to their realm Bavaria and Thuringia, two districts well beyond the ancient Roman world. The Franks themselves spread little south of the Loire River. The north and the south remained noticeably distinct from each other in blood and language. Politically, too, the kingdom was repeatedly divided and reunited. The unity of the Frankish rule was preserved by the cooperation of the kings in foreign relations, by the identity of law and custom in governing, and last but not least, by the bond of a common religion and hierarchy. In fact, historians agree that union with the Church was the strongest prop of the Frankish kingdom.

418. The Mayors of the Palace. — Many of the later Mero- wingian kings were weak and indolent, and allowed the real power to slip from them into the hands of the mayors of the palace. These officials were originally the chiefs of the royal household, but the very nature of their position and the incapacity of the kings enabled them to seize, one by one, all the powers of government. They finally became the actual rulers and even made their office hereditary. The last of the Merowingians, called the Do-nothings, were merely the nominal heads of the state. Once a year, however, they issued from their retirement, and with the rude pomp of their ancestors were driven on an ox-cart in stately procession to the popular assembly, the Mayfield (§ 439).

The greatest of the mayors of the palace was Pippin of Heristal, who succeeded in reuniting almost the whole Frankish kingdom under his sway, thereby securing the ascendancy of the Teutonic element. His son, Charles Martel (the Hammer), is more famous still. He firmly established his power throughout the entire realm and made the Frankish kingdom the most powerful state in western Europe.