The following is an excerpt (pages 145-155) from Ancient and Medieval History (1946) by Francis S. Betten, S.J. Although some information may be outdated, the Catholic historical perspective it provides remains pertinent. Use the link at the bottom of post to read the previous/following pages. Use the Search box above to find specific topics or browse using the Resources tab above.

CHAPTER XV

THE GRAECO-ORIENTAL WORLD

ALEXANDER THE GREAT AND HIS EMPIRE

174. Alexander the Great. — Philip II of Macedonia was assassinated in 336, two years after the battle of Chaeronea. He was just ready to begin the invasion of Asia. This enterprise was taken up by his son Alexander, 336-323 B.C.

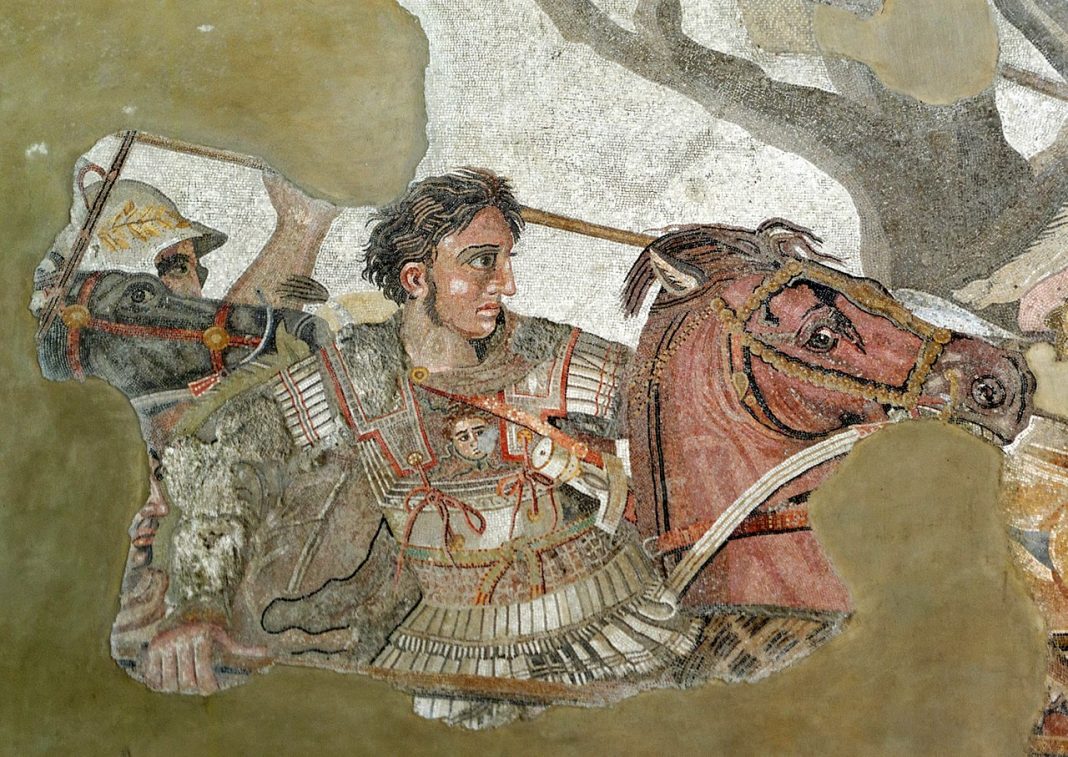

From his father Alexander had inherited his sagacious insight into men and things, and his brilliant capacity for timely and determined action. To his mother Olympias, to whom he ever bore a filial devotion, he owed a delicate sympathy for the weak, a faithful attachment to friends and benefactors, and that magnetic character which gained him the enthusiastic adherence of the thousands that followed him to the ends of the world. He was, however, especially in his later years, subject to terrible outbursts of anger. He admired Homer’s works and knew the whole Iliad by heart. Aristotle, the great philosopher (§ 188), directed his later education, and taught him to admire art and science, and brought him into sympathy with the best of Greek culture. Alexander proved a rare military genius. He never lost a battle, and never refused an engagement. Like his father he could also be shrewd and adroit in diplomacy, though unlike his father he always retained a certain straightforwardness and honesty in his dealings with friend and foe.

175. Alexander and the Greeks. — At his father’s death Alexander was a stripling of twenty years. No one thought that he could hold together the realm which Philip II had built up by force and cunning. Revolts broke out everywhere. But with marvelous rapidity Alexander struck crushing blows right and left. He restored order in Greece, and quieted the savage tribes of the north and northwest. The city of Thebes, upon the news of Philip’s death, revolted again. Alexander soon stood before its walls, conquered and destroyed it, leaving only the temples and the house of the poet Pindar intact, and sold the population into slavery. This terrified all other states into submission, and Alexander organized the common army of Hellas for the overthrow of the Persian Empire.

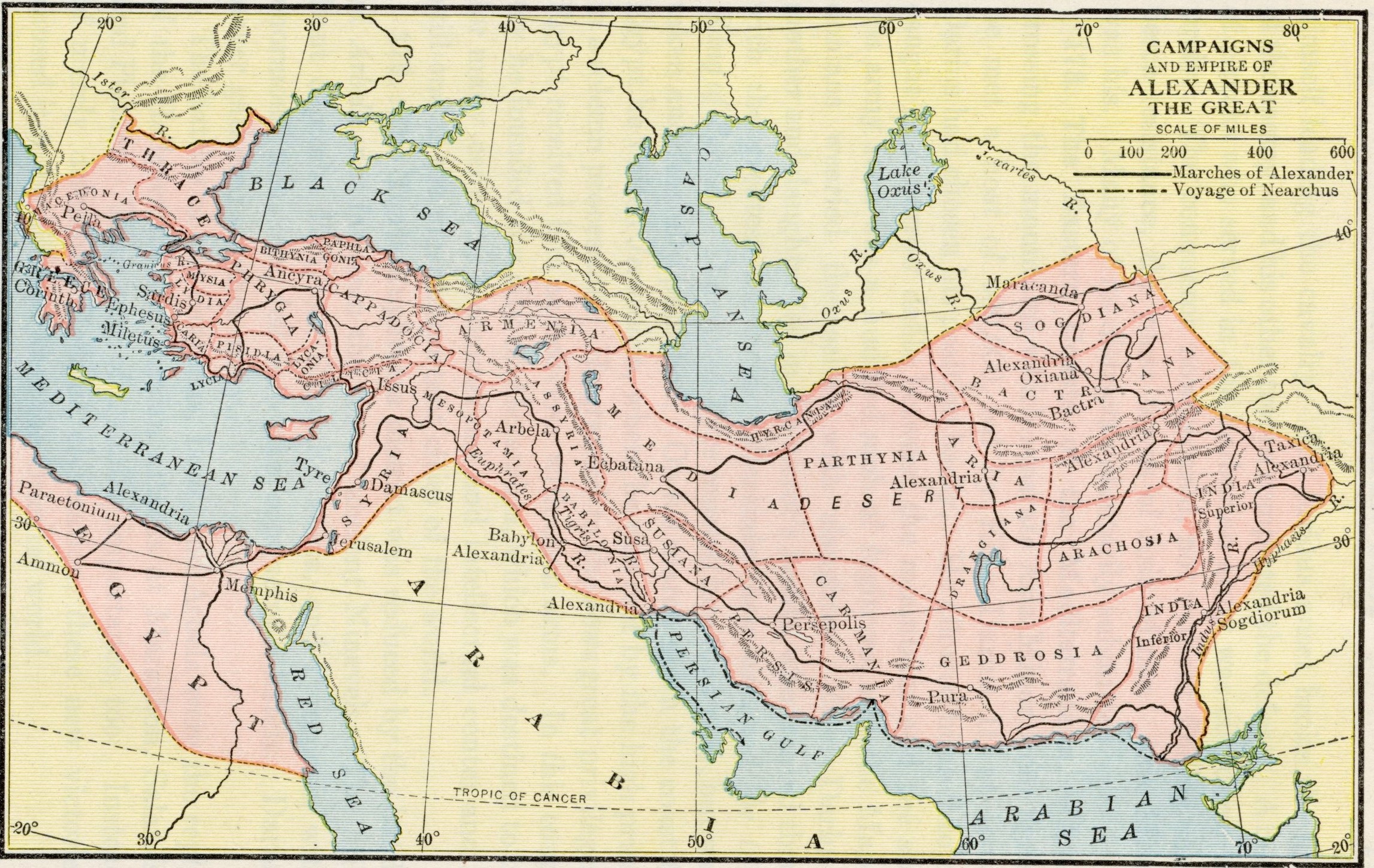

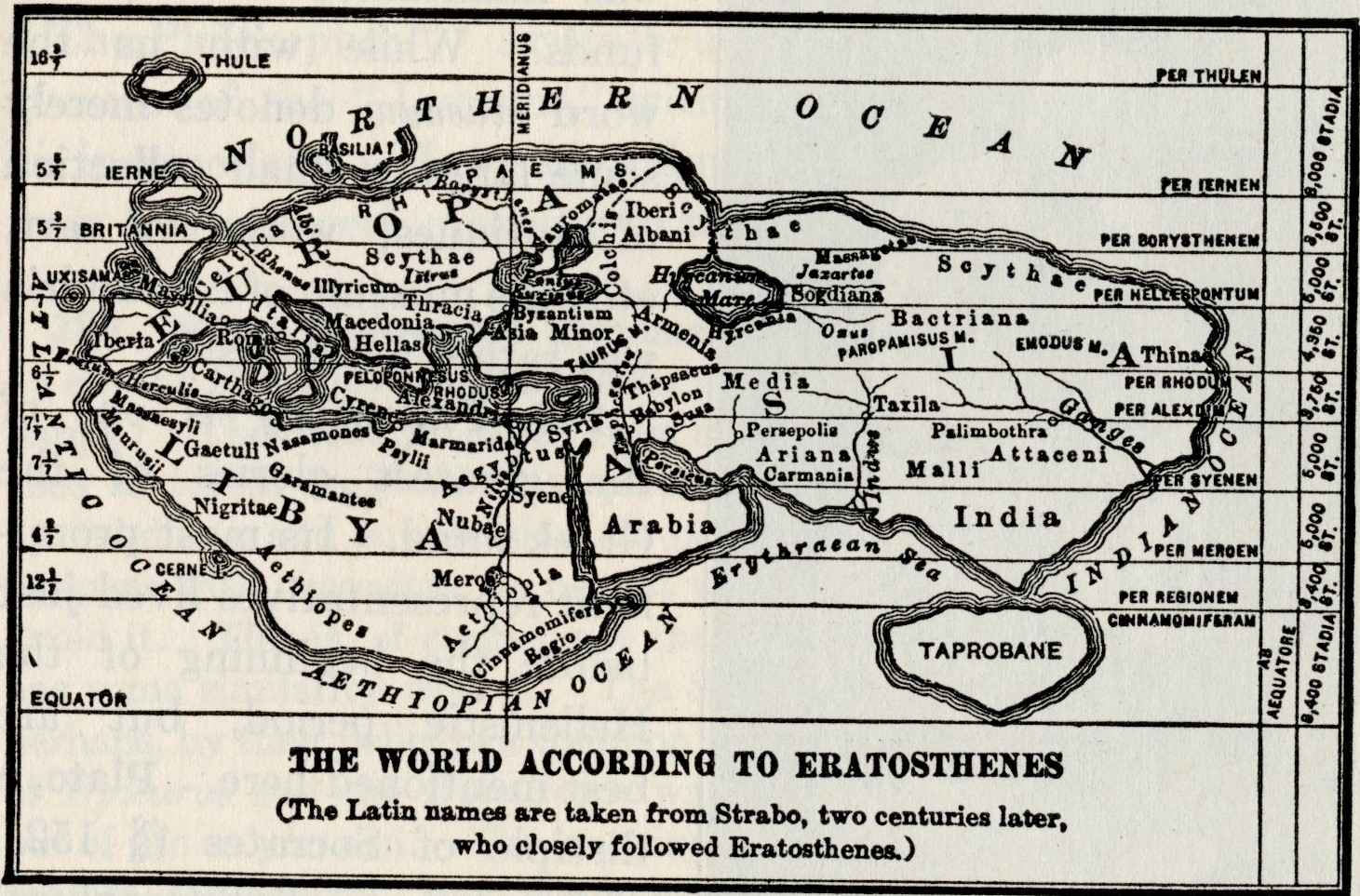

176. THE PERSIAN CAMPAIGN. — In the spring of 334 Alexander, at the head of 35,000 picked troops, crossed the Hellespont to meet the hundreds of thousands which the Great King could oppose to this handful of men. The route of march is best studied by the map facing this page. The students should use the “scale of miles” to measure the enormous distances. The conquest of Persia falls into four sections. Each of the first three of them is marked by one great battle.

177. Asia Minor. — The Persian satraps gathered their army on one side of the little river Granicus. With the rashness which was one blot upon his military skill Alexander crossed the river, himself leading the cavalry. His furious onset broke the lines of the enemy, and his other troops completed the defeat. A body of Greeks who served in the barbarian army was cut down entirely. The conqueror now secured, not without finding some fierce resistance, the coast towns of Asia Minor. Asia Minor was his. Many of its districts voluntarily submitted.

178. The Eastern Coasts of the Mediterranean. — After crossing the mountains which separate Asia Minor from Syria, he met a host of 600,000, led by King Darius II, at Issus. Darius had chosen his position badly. He allowed himself to be caught in a narrow defile between the mountains and the sea. His army soon was a huddled mob of fugitives, and the Macedonians wearied themselves with slaughter. Even Darius’s mother and daughter fell in the victor’s hands, who treated them with the greatest kindness. Alexander now assumed the title King of Persia. The city of Tyre resisted him for a year, but was taken and fearfully punished. On his march down the coast to Egypt he visited Jerusalem, where he was met by the high priest in a solemn procession. He granted to the Jews great privileges. Egypt received him as deliverer with open arms. In this country he founded the city of Alexandria, which was destined to be for many centuries a commercial and intellectual center and is still one of the most important cities of the world.

179. The Tigris-Euphrates district was reduced by the battle of Arbela, not far from the site of ancient Nineveh. The brilliant capitals, Babylon, Susa, Ecbatana, and Persepolis, with enormous treasures, fell into the conqueror’s hands. Darius never gathered another army.

The battles of the Granicus, Issus, and Arbela were the reply of the Hellenes for the Persian attacks at Marathon, Salamis, and Plataea. They were of a similar importance, too. Instead of merely defending Hellenic civilization, these new victories caused it to be diffused over the Oriental world.

180. The Farther East. — The conquest of the eastern part of the empire was attended by much greater hardships, because the marches often led through deserts and other places difficult to pass, and because here were met nations who had not lost their primitive vigor. Darius was assassinated by one of his own satraps. Alexander marched as far as the Indus River and received the submission of Porus, a mighty Indian king. At last his Macedonians refused to go any farther. He returned to Babylon, which he intended to make his capital, and devoted the remaining two years of his life to the organization of his vast empire. He died of fever in 323.

181. ALEXANDER’S HIGHER AIM: THE MINGLING OF WEST AND EAST. — During and after his war Alexander’s aims rose to a higher level. He wanted to be more than merely an avenger of Hellas. He wished to see the two civilizations, the Hellenic and the Oriental, merged into one common culture, to which each should contribute its best elements. He encouraged intermarriages between his own men and the daughters of Persians; appointed Asiatics to high positions; adopted the Persian dress and Persian customs. On the other hand he had Persian youths trained in the Hellenic fashion; introduced imitations of the Panhellenic games; erected Greek temples and theaters; encouraged the reading and study of Greek literature; and let it be known that an educated man must know Greek. As a very efficient means he established many Greek colonies. Often these were merely the settlements of his veterans. But enterprising younger men would flock to them from all over Hellas. The locations were so well chosen that many have existed for centuries and are still important places, as Herat and Kandahar, and, above all, Alexandria. These cities were laid out according to well-considered plans, and had good paved streets. Each of them was a center of Hellenic ideas and Hellenic culture. Gradually natives, too, would move in, and assume Greek language and customs. Several of these colonies were named Alexandria.

182. Thus arose the Hellenistic civilization, the main elements of which were indeed those of the Hellenic, modified as they were by the contact with Oriental views and ideas. It is to the undying credit of Alexander the Great that he deliberately brought about the blending of these two cultures, and that in so doing he deliberately gave preference to the Hellenic — that part which, without any doubt, bore the truest marks of greatness. Few men have done what Alexander the Macedonian did for the genuine (natural) advancement of mankind at large.

THE SUCCESSOR STATES

183. Alexander’s Empire Broken Up. — It was a calamity for the world that Alexander died so soon. His plan of one great political unit of the whole known world was not to be realized. His empire lasted only a few years. He left no son that was able to succeed him. His generals divided the enormous lands among themselves, first under the title of governors, then as independent kings. A period of bloody wars followed. Out of this struggle emerged, besides some smaller states, three great kingdoms: Syria, under Seleucus; Egypt, under Ptolemy; Macedonia, under Cassander. Syria was practically the successor of the old Persian Empire, but it quickly lost the lands east of the Euphrates. The Ptolemies in Egypt simply succeeded to the position of the ancient pharaohs. All these states, including the smaller ones, vigorously continued the Hellenizing policy of Alexander. They existed until, at various dates, they became provinces of the Roman Empire.

When the wars of the succession were hardly over, an unexpected danger threatened civilization. From their homes in western Europe strong bands of Celts invaded Greece and Asia Minor, carrying death and destruction everywhere, and plundering, the wealthy cities on their march. Their inroads, beginning in 278 B.C., continued several years, until large hordes of them were settled as colonists in the center of Asia Minor, in a country afterwards called Galatia. Though accepting much of Hellenic culture, they retained their identity and language for several centuries.

184. Greece. — The new kingdom of Macedonia claimed the allegiance of the Greeks. These made several attempts, partly successful, to regain their political liberty. The most remarkable feat was the establishment of the Achaean League, a kind of “United States,” consisting of members with equal rights and having a central government. For half a century it defended Greek liberty successfully. At last, in a quarrel with Sparta, its greatest leader, Aratus, otherwise a very able statesman, treasonably called in Macedonia for assistance. The league became subject to that power. It was allowed to continue, and it even survived Macedonia by some years.

THE HELLENISTIC WORLD

185. Centers of Hellenistic Culture. — The city of Athens always maintained its place as the teacher of everything great, learned, and elevating. For centuries men flocked to it from all parts of the world for the purpose of study, or to perfect themselves in what they had learned elsewhere. Athens had, however, great rivals in the flourishing cities around the head of the Mediterranean. At Rhodes there existed a most renowned school of oratory alongside other institutions of learning. On the continent of Asia there were Pergamum in Asia Minor, Antioch in Syria, Alexandria in Egypt. Not only did these cities boast of a large number of first-class scholars, mostly with Greek names, but the enormous wealth of their citizens and kings enabled them to establish institutions for the promotion of scholarship far grander than those of Athens, and to carry out enterprises which in size and expensiveness, though not in taste and beauty, dwarfed the productions of the city of Pericles. Greece, always holding a very prominent place in the realm of intellectual and artistic activity, was now only one of several countries where a high-class civilization had found a congenial home.

186. A brisk literary activity was going on in these and hundreds of minor centers. A number of poetical works were produced, though none of them equaled the immortal epics of Homer or the grand dramas of Sophocles. Men tried to put forth writings whose language was in every way perfect, though the content did not come up to the masterpieces of former times. Never were the poems of Homer and other works more carefully and painstakingly studied as to the shade and sound of every word. The Hellenistic scholars examined the manuscripts of such writings, to find out which was the best and deserved to be followed. The study of grammar was paramount. The language was to be known not only practically but also theoretically. The principal home of these studies was Alexandria.

187. Science made great strides during the Hellenistic age. Nearly all proofs of the sphericity of the earth were known at that time, as they now figure in our textbooks of physical geography. Eratosthenes, born 276 B.C., is by many considered the founder of the science of astronomy. Some scholars were convinced that men could reach the eastern coast of Asia by sailing west from Europe. Architecture, painting, and sculpture, needless to say, were practiced on a large scale. All the Hellenistic kings made it their special business to attract talented artists to their brilliant courts, and to enlist their services for the production of numerous costly and grand enterprises of all kinds.

187. Science made great strides during the Hellenistic age. Nearly all proofs of the sphericity of the earth were known at that time, as they now figure in our textbooks of physical geography. Eratosthenes, born 276 B.C., is by many considered the founder of the science of astronomy. Some scholars were convinced that men could reach the eastern coast of Asia by sailing west from Europe. Architecture, painting, and sculpture, needless to say, were practiced on a large scale. All the Hellenistic kings made it their special business to attract talented artists to their brilliant courts, and to enlist their services for the production of numerous costly and grand enterprises of all kinds.

These studies were greatly assisted by the establishment of museums. The model museum was that of Alexandria. It had a library of a million (handwritten) books, with scribes to make careful copies, and explain difficult passages by annotations. It had observatories and botanical and zoological gardens, with collections of all kinds. There was a staff of learned men, called librarians, who devoted their whole lives to study and teaching.

The entire costly institution was maintained from public funds. While with us the word museum denotes merely some large or small collection of antiques, works of art, etc., the museum of Alexandria was rather a university.

188. Philosophy is one of the greatest glories of the Greek mind. Its most prominent representatives lived just before the beginning of the Hellenistic period, but are best mentioned here. Plato, a disciple of Socrates (§ 152), elaborated a vast philosophical system. He died in 347 B.C. His writings strikingly display before us the infinite greatness, goodness, and wisdom of God — One God — His sovereignty over the world, the spirituality of the human soul. Though these truths are mingled with errors of the most serious kind, his philosophy, taken all in all, exhibits a noble mind and a penetrating intellect, which grappled with the problems of life with considerably more success than any of his predecessors. Aristotle, for many years Plato’s disciple, far outshines his master. He died a year after Alexander, in 322 B.C. In his investigations he proceeded from life and experience. One of Plato’s errors was that our ideas are born with us. Aristotle taught that they are acquired through the operation of the senses, which convey to the intellect the material upon which the latter begins its activity to rise to spiritual (immaterial) concepts. Although not free from very grave shortcomings, Aristotle’s system is so nearly perfect that its chief outlines and very many of its details became the fundamental doctrines of the great Christian philosophers of the Middle Ages. St. Thomas and the other Scholastics refer to him simply as “The Philosopher.” Aristotle used to walk about, in the shady avenues of the “Lyceum,” with his disciples, while imparting his instructions. Hence his followers are also called Peripatetics, from a Greek verb meaning to walk up and down.

189. Minor Philosophic Systems. — Two schools are best described by stating that they tried to answer the question: How can man become happy? The Stoics, so called from the stoa in which their founder Zeno used to teach, reply to this question: by practicing “virtue,” i.e., by subduing and suppressing all passions and emotions. Everything happens with necessity; so bear it without feeling, because you cannot avoid it. This is, of course, not the Christian virtue of patience, but it has some similarity with it. The Stoics came nearer to Christianity, perhaps, by their belief in a common brotherhood of all men. The reply of Epicurus and the Epicureans was different: Get as much pleasure out of life as you can. The warning which they added, that this would require self-control, was commonly disregarded by their followers. Another school was that of the Skeptics, who taught that we can know nothing with certainty and that we must doubt everything. The Cynics ostentatiously threw away all the comforts of life and sneered at the love of family, country, and religion.

190. Limitations of Hellenistic Civilization. — Let the student recall the limitations of Hellenic culture as given in § 153. They remained in full force during the Hellenistic period and were aggravated by the contact of Hellenism with Oriental customs. The position of woman had not been honorable in Greece. The Hellenistic kings (Alexander himself gave the example) at once adopted polygamy. The harsh treatment of the Oriental slaves was in no way improved. The new connections between East and West enormously increased the wealth of the higher classes and greatly widened the gap between the rich and the poor. The philosophers, Plato and Aristotle included, who gravely discoursed on human happiness and moral rights and duties, did not so much as dream of the man in the street, let alone the slave. The moral degradation of Hellas, enhanced by the vices of the decaying Orient, had started upon its march through the countries on the Mediterranean.

A LAST WORD ON GREEK CULTURE

The Greek contributions to our civilization can hardly be named in detail as can those of the Oriental nations. Egypt and Babylonia gave us some very important outer features. Greece, as it were, infused a new spirit. Hers was essentially an educational task. In the development of all the purely secular branches of human knowledge and endeavor no nation has had an equally large share. The Greeks became the teachers of the Romans. “Conquered Greece caught her fierce conqueror.” Roman poetry and oratory and whatever there was of Roman philosophy shaped itself after Greek models. And Rome passed on the treasure she had received to the peoples of the later centuries. Thus Greece through Rome is still teaching in our schools. The chief principles of Christian philosophy were taken over bodily from the sages of the Aegean Sea. Greek education helped to prepare the world for the coming of Christianity and furnished the language in which the glad tidings of the New Testament were first written down in human speech. Yet Greek civilization was modified by the matter-of-fact genius of conquering and ruling Rome. It came to the largest part of Europe through the Romanized Celts, again to be affected by the mind of the Teutons. There is above all the paramount influence of the religion of Jesus Christ with its Heaven-born truths and ideals. It was the task of Christianity to undo the enormous harm which Greek vice, increased by the gross immorality of the Orient and propagated under Roman sway to the remotest corners of the world, had brought upon mankind. None of these factors may be omitted when judging of the contributions of Greece to our present civilization.