The following is an excerpt (pages 261-264) from Ancient and Medieval History (1946) by Francis S. Betten, S.J. Although some information may be outdated, the Catholic historical perspective it provides remains pertinent. Use the link at the bottom of post to read the previous/following pages. Use the Search box above to find specific topics or browse using the Resources tab above.

CHAPTER XXVI

A CENTURY OF DECLINE (180-284)

THE STORY OF THE EMPERORS

347. General Character of the Emperors. — With Commodus, the son of the great Marcus Aurelius, began the period of the barrack emperors, who were set up by the praetorians in Rome or the troops in various parts of the Empire and fell, most of them, by the hands of the same or other soldiers. It was now that the uncertainty of the succession bore its worst fruits (§ 328). Once the praetorians raised an emperor whom they killed three months later, offering the throne to the highest bidder, and selling it to one who promised to each soldier a thousand dollars. By far the greater number who thus rose to the supreme power were unfit to rule and desecrated their position by vices of all kinds. There were, however, several good rulers among them, who saved the state both from anarchy and from the invasion of foreign enemies.

348. Alexander Severus (222-235), though not gifted with the sternness which was necessary in so troublesome a time, greatly benefited the empire. His court was simple and pure, his actions at home dictated by charity. Under him Roman law was better developed and organized by his friend Ulpian. In the East the Parthian kingdom, which had been the permanent foe of Rome, gave way to a new Persia, which inherited the Parthian enmity against Rome. Alexander Severus with some difficulty defended the frontier. He also repulsed the Teutons, who with renewed force repeated their inroads across the Rhine and Danube. The thirteen years of his reign were an oasis of peace and plenty in the dreary third century. He had been raised by the soldiers and died at their hands.

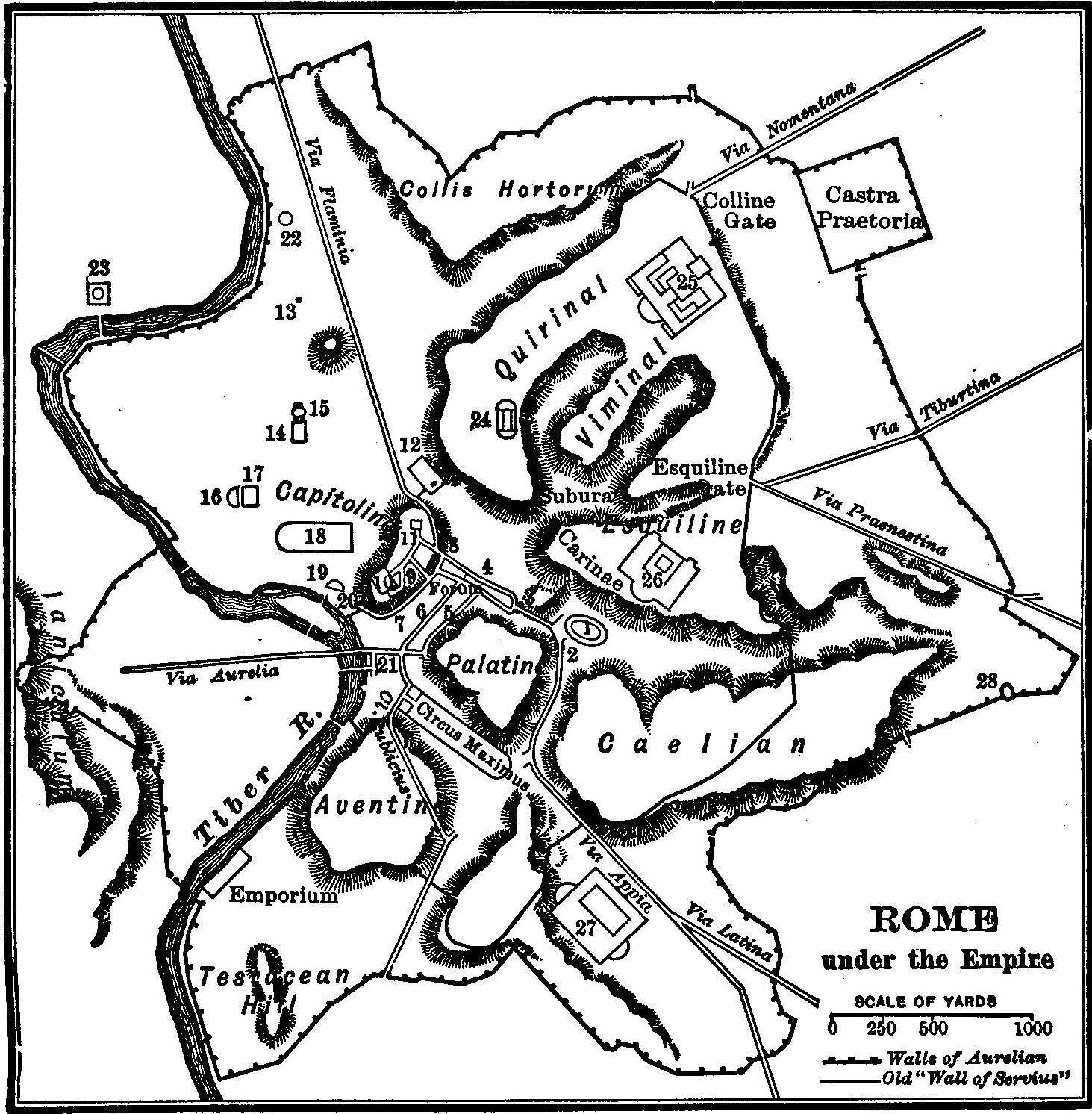

2. Arch of Constantine.

3. Arch of Titus.

4. Via Sacra.

5. Via Nova.

6. Vicus Tuscus.

7. Vicus Jugarius.

8. Arch of Septimius Severus.

9. Clivus Capitolinus.

10. Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus.

11. Arch.

12. Column of Trajan.

13. Column of Antoninus.

14. Baths of Agrippa.

15. Pantheon.

16. Theater of Pompey.

17. Portico of Pompey.

18. Circus Flaminius.

19. Theater of Marcellus.

20. Forum Holitorium.

21. Forum Boarium.

22. Mausoleum of Augustus.

23. Mausoleum of Hadrian.

24. Baths of Constantine.

25. Baths of Diocletian.

26. Baths of Titus.

27. Baths of Caracalla.

28. Amphitheatrum Castrense.

349. Phantom emperors followed one another in bewildering confusion. Among them Decius, able enough, used a considerable part of his energy during the short two years which the soldiers allowed him to rule for a fierce persecution of the Christians. The emperor Valerian was captured by the Persian king Sapor and died in humiliating captivity. In the sixties there were so many claimants of the throne that this time is referred to as the age of the “Thirty Tyrants” (§ 168). The Empire seemed in ruins. It was sunk in anarchy and split into fragments by the jealousies of the rival legions. The Germanic barbarians worked their will in the frontier provinces. The Persians made use of the Empire’s weakness for conquests.

350. Aurelian (270-274) undertook vigorously the restoration of law and order in the interior and drove the barbarians back across the boundaries. In Gaul he quelled an attempt at independence. In the East he defeated Zenobia, who had made herself queen of a large territory. Once in his reign the German Alemanni penetrated as far as the Po, and threw Italy into a panic. Rome, which had not feared an invader since the days of Hannibal, might now be attacked by a new foe. Aurelian surrounded the city with mighty walls — a grand work, which, however, showed how the times had changed. Aurelian’s five years compare well with the five years of Caesar. His early death was a calamity for the Empire.

After Aurelian’s death there followed another time of confusion lasting until 284, when Diocletian, the man who was going to put the Empire upon an entirely new basis, grasped the reins of government.

CONDITIONS IN THE EMPIRE

351. The third century was a period of decline. The bad

emperors were too many, and the reigns of the good emperors were too short. The wonderful machinery of Roman administration refused to work here and there, and sometimes everywhere. The safety on land and sea was no longer what it had been. The officials, not always kept in check by the fear of a strong central government, fell back upon their old practices of oppression. The frontier provinces fared the worst because the barbarians on all sides availed themselves of the distracted state of the Empire to invade them repeatedly and carry off both goods and people. All classes of people, especially the business world, suffered greatly under this lack of law and order.

352. Decline of the Population.—With the spread of immorality the people became more and more averse to honorable marriage and the responsibilities of parenthood. Besides, the greater part of the population consisted of slaves, who on account of their condition could not marry or rear families. The Teutonic barbarians, too, sometimes carried off the population of entire provinces into slavery. We know that on one occasion Marcus Aurelius, after a victorious war with the Quadi, forced them to give up 50,000 Roman captives. Such successes, however, could not always be effected. Worst of all, during the previous century, in 166, a new Asiatic plague swept from the Euphrates to the Atlantic, carrying off, we are told, half of the population. This plague later on returned several times, desolating wide regions and demoralizing agriculture and industry. It speaks very favorably for emperors like Aurelian, that with the empire thus afflicted they were able to ward off foreign attacks, or at least come to honorable terms with the enemy. One of the means often used was to give to turbulent Teutonic tribes land in some desolated region within the empire and thus make peaceful settlers of dangerous enemies. This as well as the allotment of land to pensioned-off soldiers filled, to some extent, the gaps left by pestilence and immorality, though it was not by far enough to stop the slow but irresistible process of depopulation.