The following is an excerpt (pages 237-260) from Ancient and Medieval History (1946) by Francis S. Betten, S.J. Although some information may be outdated, the Catholic historical perspective it provides remains pertinent. Use the link at the bottom of post to read the previous/following pages. Use the Search box above to find specific topics or browse using the Resources tab above.

CHAPTER XXV

TWO HUNDRED YEARS OF PEACE — 31 B.C. TO 180 A.D.

GENERAL CHARACTER OF THIS PERIOD

313. With the age of Augustus the history of Rome changes into the history of the Empire at large. It is no longer centered so exclusively in the city of Rome. The time is at hand when by following up the principles of Caesar and Augustus the right of citizenship will be extended to all the inhabitants of the Roman lands. Rome is still the capital, the seat of the central government. But the eyes of that government are now directed to the welfare of the whole, instead of to the enrichment of a limited number of Roman grandees. Never before, and never after, did a territory so vast as the Roman Empire enjoy so long a period of peace. The task of the government was to guard the frontiers and to promote security in the interior. On the whole this task was well performed.

Practically all the emperors of the two centuries were good rulers. The few who were not did not live long enough to do much harm. Their vices made them hated at Rome. But the administration of the provinces went on along the channels established before. Even the fact that some of them persecuted Christianity must not interfere with our verdict that they gave in other regards a good government to the Empire.

314. The term “ empire ” has so far been used in this book of a dominion in which one land or country holds the place of a ruler, while the others are its subjects. In Roman history, too, so far, we have employed it in this sense. From now on it changes its meaning. It denotes a state all the parts of which are on an equal footing (though this was not the case right away in the Roman Empire), and which is ruled over by monarchs whom we style emperors. — The Roman emperors are often referred to as Caesars, because each of them adopted this title as part of his personal name. (H. T. F., “Empire.”)

THE STORY OF THE EMPERORS

Three groups of emperors ruled during this time: the Julian emperors, the Flavian emperors, the “five good emperors.”

THE JULIAN EMPERORS

315. Augustus, the First of the Julian Emperors. — We must still report one interruption of the peace of his forty years’ reign. He wished to reduce the Germans on the eastern bank of the Rhine to subjection. The attempt ended in disaster. In the battle of the Teutoburg Forest, 9 A.D., the Roman legions were entirely destroyed by the enraged Germans under the leadership of Arminius.

316. Tiberius (14—37), Augustus’ adopted son, the next emperor, was loved and revered in the provinces for the indefatigable care with which he watched over their welfare, and the sternness with which he held every Roman official to his duty. On one occasion he rebuilt, at his own expense, twelve cities which had been destroyed by an earthquake. In Rome, he was looked upon as a gloomy tyrant. He had grown suspicious of his surroundings, and many guilty and innocent persons suffered cruel death on that account. During his reign occurred the crucifixion of Our Lord.

317. Caligula (37-41), Tiberius’ adopted son, had been a promising youth. But crazed by power or some mysterious illness, he filled the four years of his reign with deeds of cruelty and madness. (He even wished to make his horse consul.) He died by the hands of assassins.

318. Claudius (41-54), a timid, gentle, awkward man, uncle of Caligula, was forced to assume the supreme power by the praetorians. His administration, to which he faithfully gave his time and efforts, was carried out chiefly by capable freedmen. Under him the Roman conquest of southern Britain took place.

319. Nero (54—68), allowed himself to be directed for several years by the great philosopher Seneca and other able men. Later on he entered upon a career of lust, cruelty, and vanity, imagined himself to be a great poet, dancer, and even gladiator, and ended his life by suicide.

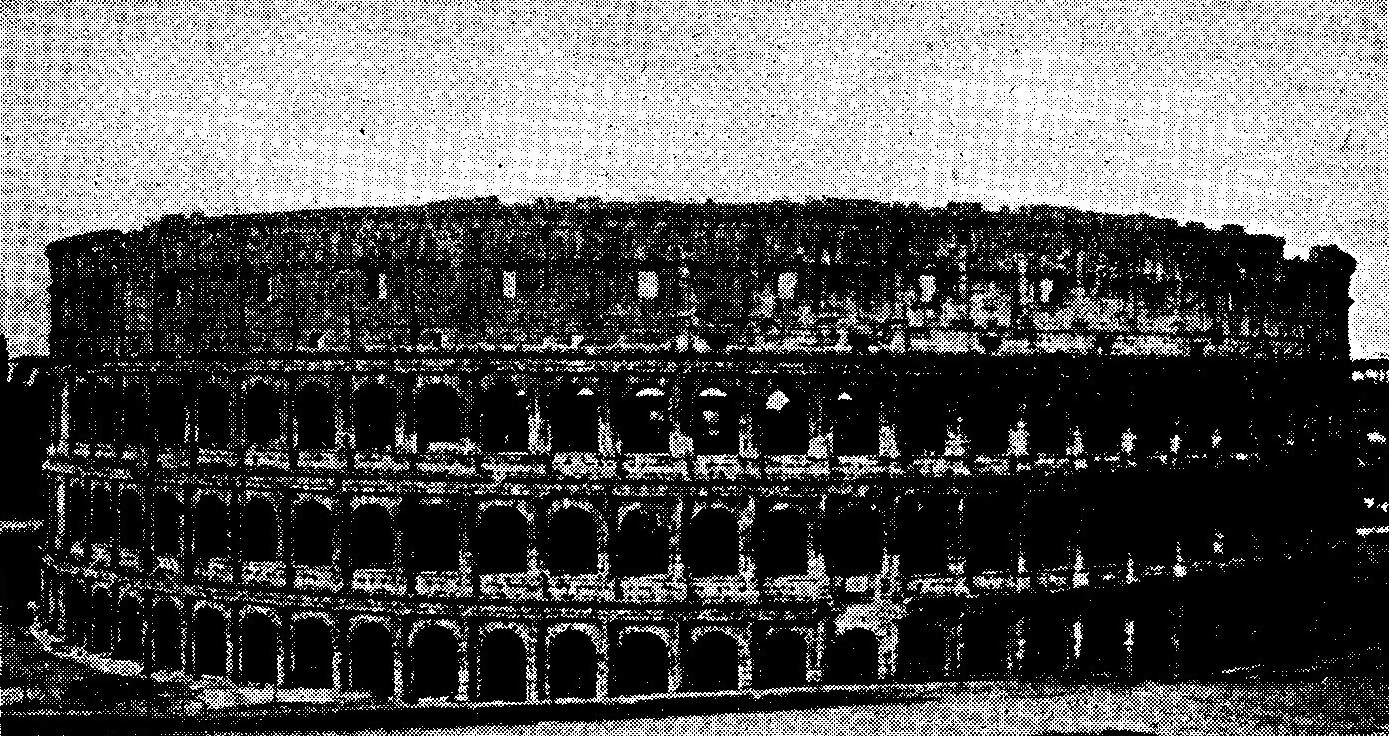

The eighty openings in each story and the ornamental columns and friezes break the monotony, but do not destroy the general impression of the colossal. In later centuries this structure served as a stone quarry for the palaces of Roman nobles, and only its huge size prevented complete destruction. The picture shows the part that is preserved. Many Christians suffered a cruel death in this structure.

During his reign half of Rome was laid in ashes. For six days and nights the flames raged unchecked. Nero himself was suspected by many of having ordered the destruction, that he might build the city up in more magnificent fashion. The Christians were accused of having started the fire. To turn attention from himself, Nero began the first persecution of the Christians. Without trial, Christians, tarred with pitch, were burned as torches in the imperial gardens; others, clothed in skins of animals, were torn by dogs for the amusement of the mob.

THE FLAVIAN EMPERORS

320. Flavius Vespasianus was proclaimed by the legions in Syria in 70 A.D., after a year of wild confusion. He dislodged several rivals who had been put up by the troops in Spain, Rome, and Gaul. He was of low parentage, but honest, industrious, experienced, and broad-minded. He gave to the Empire nine years of peace, during which many magnificent buildings were erected.

The most striking event in his reign was the destruction of Jerusalem, 70 A.D. The Jews had been under kings appointed by Rome or directly under Roman governors since 63 B.C. (§ 286). Jesus of Nazareth, whose followers were now establishing a spiritual kingdom, they had rejected. But they stuck blindly to the idea of a messiah who would free them from foreign domination. This idea, which became a mania with them, together with blunders made by the Roman governors, drove them into a desperate rebellion. Vespasian, still a general, was ordered by Nero to suppress it. When proclaimed Emperor, he departed for Rome. His son Titus laid siege to Jerusalem. He met with a fierce resistance. Though a bloody war went on inside the city between two parties, and though hunger and disease raged fearfully, nobody thought of surrender. The city went up in flames. The miserable remnant of the population were sold into slavery. The Jews never again formed a state of their own.

321. Titus (79-81), won general admiration and affection by his kindness. He considered a day as lost on which he had not made anyone happy. In the first year of his reign Mount Vesuvius, which had been thought to be an extinct volcano, belched forth in a terrible eruption, destroying the countless villas and vineyards upon its slopes and burying under ashes the two cities of Herculaneum and Pompeii. After lying hidden under the new surface of the earth for seventeen hundred years, these cities were discovered and are being more and more excavated, so that to-day the visitor can walk the very streets of a Roman city and view its houses, shops, theaters, and temples.

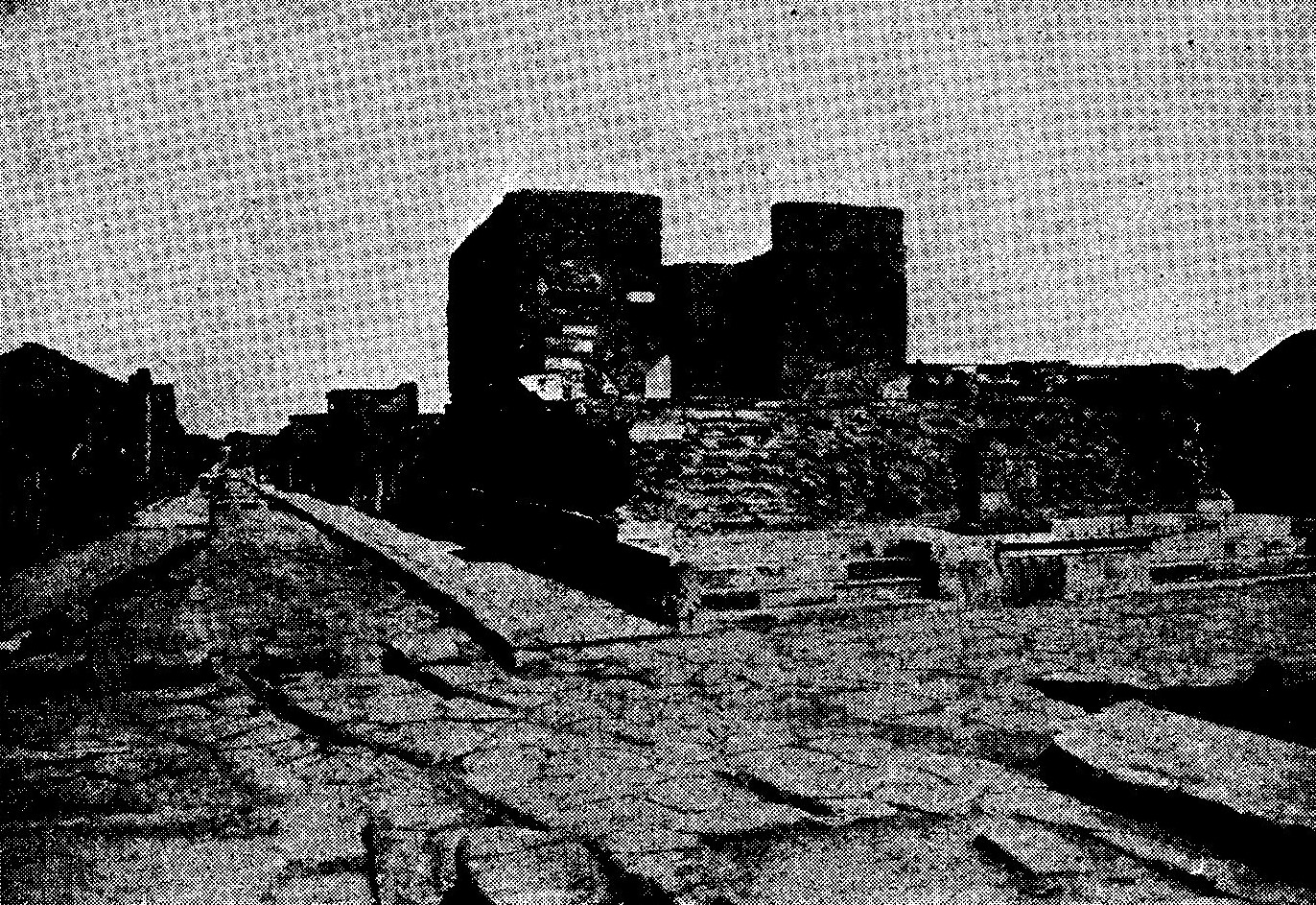

The high walls are the remains of the temple proper. Some of the steps leading up to it are still visible. It had a colonnade (§ 110) in front; fragments still mark the place of the columns. Before it appears the base of a statue. Note the heavy pavement of the streets, and the stepping stones leading from sidewalk to sidewalk.

322. Domitian (81-96), the third of the Flavians, brother of Titus, was a stern ruler. A plot of the nobles against him was put down with cruelty. Under his rule the conquest of Britain as far as the highlands of the north was completed. He stained his government by a new persecution of the Christians. He was assassinated by members of his household.

THE FIVE GOOD EMPERORS (96-180 A.D.)

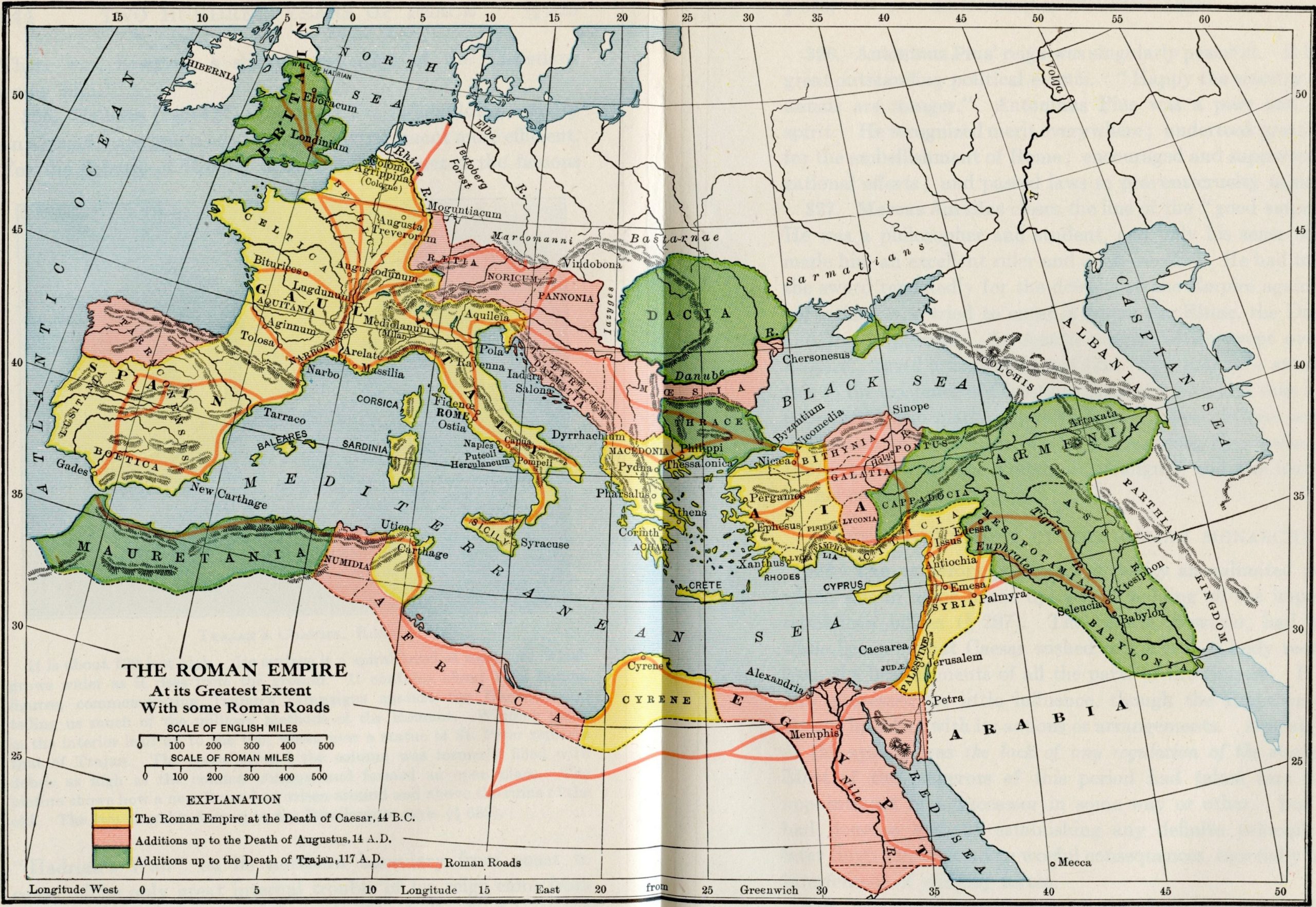

These rulers succeeded in giving to the country a remarkable period of prosperity. Three of them were born Spaniards, a fact which indicates that the equality between the Italians and the provincials had made rapid progress.

323. Nerva, an aged senator, used the sixteen months of his reign to undo the harm done by the cruelty of Domitian. To secure a good succession he adopted the able Spaniard Trajan as his son and co-emperor. The next three rulers of this group followed the same practice of adopting their future successors.

324. Trajan (98-117), is the last great Roman conqueror. He added to the Empire the province of Dacia, north of the lower Danube, which was thoroughly Romanized by the immigration of numerous settlers. Hence it is that the present Rumanians speak a Latin language, and are to some extent descendants of Romans. In the East he conquered wide provinces beyond the Euphrates, which, however, were given up under his successor. Despite his wars he was an excellent administrator, a great builder of roads and public works. He took steps for the care of orphans, and made laws for the protection of the slaves.There was, however, a slight persecution of the Christians under him.

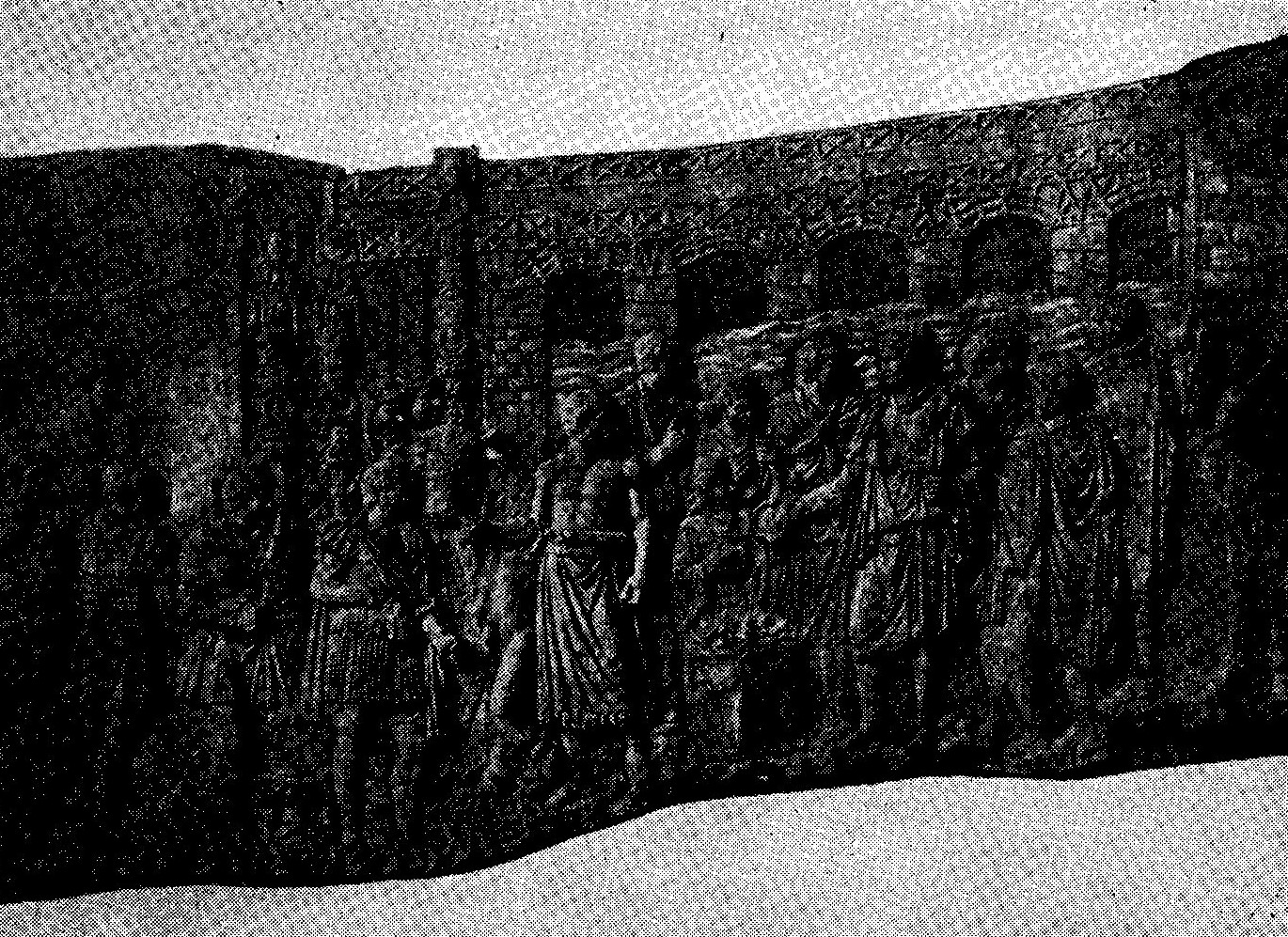

Trajan is sacrificing a bull at the wooden bridge built by his engineers over the Danube.

325. Hadrian (117-136), continued Trajan’s building activity on a larger scale, and made the central government more efficient. For the defense of Roman Britain he constructed the famous “Hadrian’s Wall” on its northern boundary from coast to coast. The only great internal trouble of his reign came from the Jews, who made another desperate but futile effort to throw off the Roman yoke in 135 A.D.

It is about 120 feet high. Its surface is a spiral band of sculpture, which grows wider as it rises from the ground. It contains about 2500 human figures, commemorating Trajan’s campaigns against the Dacians, and telling us much of the military methods of the Romans. Winding stairs in the interior lead up to the top, where now a statue of St. Peter replaces that of Trajan. The space around the column was formerly filled with debris as high as the column stumps, and formed an open place. The picture shows how a new Rome had arisen around and above the ruins of the old. The two churches belong to the Renaissance style (§ 682).

326. Antoninus Pius’ reign was singularly peaceful. It had no great outstanding political events. “Happy the country whose annals are meager.” Antoninus Pius was a pure and gentle spirit. He recognized merit everywhere; undertook great works for the embellishment of Rome; encouraged and supported educational efforts; and passed laws to prevent cruelty to slaves.

327. Marcus Aurelius closes the line of the “good emperors.” He was a philosopher and student, and only his sense of duty made him an excellent ruler and even warrior. He had to draw the sword repeatedly for the defense of the Empire against the barbarians who tried to enter it across the Rhine, the Danube, and the Euphrates. An Asiatic plague, which swept over the Empire, caused a terrible loss of life. The populace attributed this to the existence of Christians in their midst, and thus a cruel persecution also marks the reign of the philosophic emperor.

The son and successor of Marcus Aurelius, Commodus (180- 192), was an infamous wretch, like Caligula, and was murdered by his officers.

THE GOVERNMENT OF THE ROMAN MONARCHY

328. The emperors possessed in reality an unlimited power, which was in name based upon their holding all the important republican offices (§ 297). The Senate, however, had meanwhile become what Caesar wished to make it, a body recruited from the best elements of all the parts of the Empire. It even now possessed no little influence, though the Emperor could always interfere with its actions or arrangements. A weak point in the system was the lack of any regulation of the succession. Most of the emperors of this period had taken care of the appointment of a successor in some way or other. But they had done so without establishing any definite principle. In later times this lack led to woeful consequences, especially by the interference of military forces.

329. Municipal government, on the whole, remained as it had been under the Republic. The difference between colonies and municipia (§ 216) had disappeared long ago. All the thousands of cities of the Empire elected their own local officers, whose titles and functions in Latin countries were more or less shaped upon those of republican Rome.

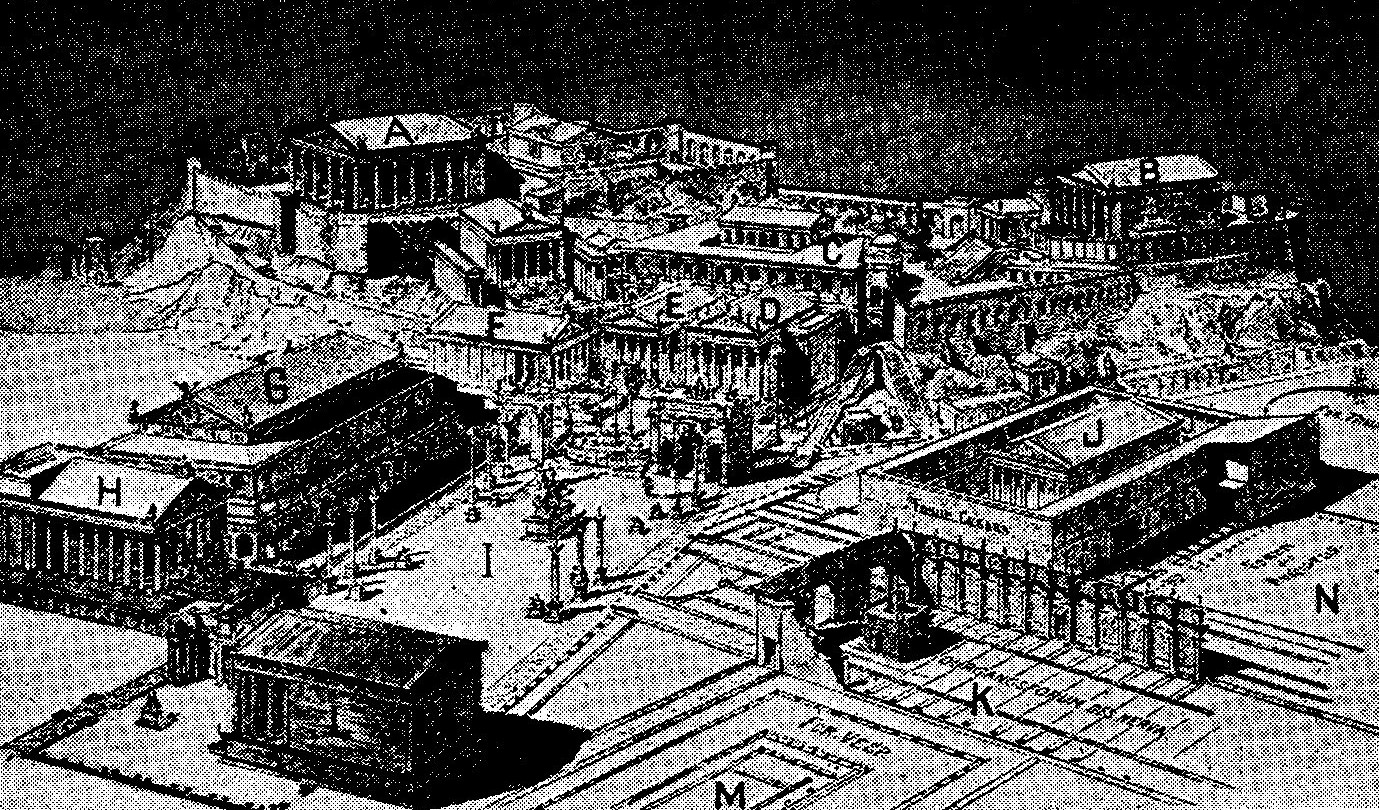

The slopes of the Capitoline Hill are clearly seen in the rear. (Some buildings have been omitted in the foreground to avoid crowding the picture.) A, Temple of Jupiter (see ground plan on page 167). B, Temple of Juno. C, Tabularium (building for the state archives). D, Temple of Concordia. E, Temple of Vespasian. F, Temple of Saturn. G, Julian Basilica (with two side aisles on each side; it was begun by Caesar and finished by Augustus). H, Temple of Castor. I, Roman Forum; at the farther end are seen the triumphal arch of Septimius Severus, and next to it the rostra, the platform for public speakers, adorned with several high columns. J and K are two “imperial forums,” i.e. large public squares surrounded by a wall and beautiful colonnades, and often containing a temple or basilica. J is the Forum of Julius Caesar; K, that of Nerva; L, Temple of Antonine and Faustina; M, place of Forum of Vespasian ; N, place of Forum of Augustus.

It is interesting to see how real the contests for office were. In the city of Pompeii no less than 1500 posters, indorsing candidates for offices, have been found painted on the walls. They probably refer only to one election. A baker is recommended for quaestor (treasurer), because “he sells good bread”; while near by an aristocrat is supported because “it is well known that he will guard the treasury.”

In Rome the old assemblies had faded away. Most of their functions had been given to the Senate. The city was ruled by magistrates appointed by either Emperor or Senate. The same was done with all the very large cities, as Alexandria, where imperial officers with a more absolute power controlled affairs. These officers were backed by detachments of soldiers, to hold the mob in check. Vigorous and able emperors were rather inclined to introduce this system, wholly or in part, into other municipalities, and to sweep away antiquated institutions which were less economic and efficient. Taken as a whole, local home government remained the rule during this period of the Empire.

330. The Provinces. — Above the towns there was no self- government. The provinces were ruled with absolute power by the governors. Provincial assemblies, which existed in some provinces, especially in Gaul, could merely advise the Emperor, or petition him, for instance against a tyrannical governor — a petition always sure of careful consideration. The governor was held strictly responsible for all his acts. Severe penalties were visited on him who neglected his duty.

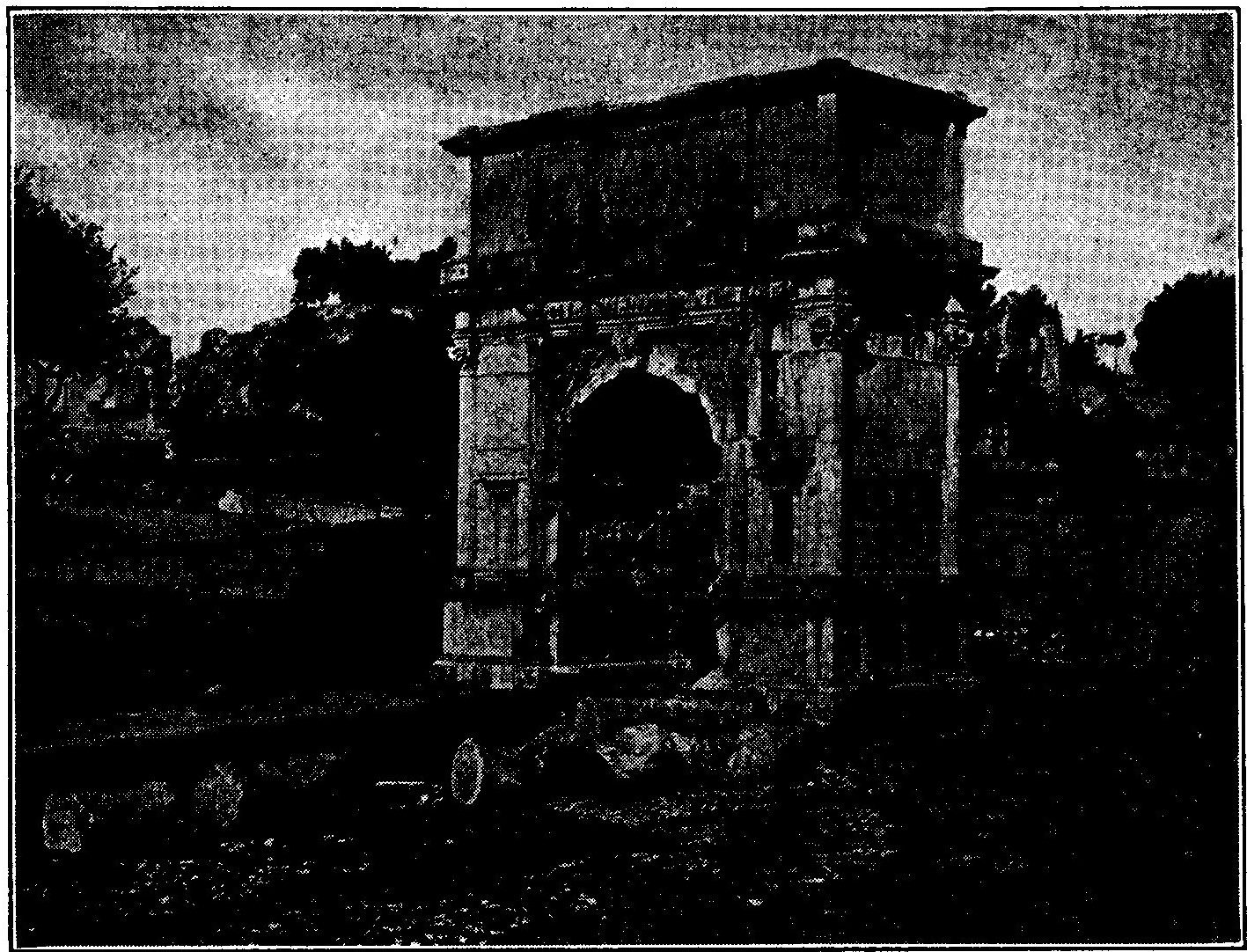

331. Taxation was no doubt heavy, though much lighter than it had been under the former rulers of the same provinces. There was a land tax; a poll tax on every citizen and trader in a town; an inheritance tax of five per cent. In some provinces there were tariff duties on goods entering or departing. Some provinces paid their tax in grain, Egypt, for instance, being obliged to furnish 1,444,000 bushels of wheat each year, to feed the hungry masses of the capital. The taxes were collected with great consideration. If a province was stricken by some public calamity, the taxes were promptly lessened or remitted by imperial order. Above all, the people saw that they were getting something in return for their taxes. The government maintained the golden Roman Peace in all the lands around the Mediterranean. It protected navigation against pirates and travel on land against robbers. It prevented extortions on the part of officials. The improved law courts of all kinds dispensed justice efficiently.

And all along the threatened borders there stood the sleepless legions guarding the Empire and its civilization against barbarian inroads.

Many things indeed which a government does to-day the Roman government did not do. It had no efficient laws for the preservation of public morality and decency. It did not of set purpose maintain or encourage the building up of complete systems of education including elementary schools or of hospitals and asylums. Creations of this kind began to rise only after Christianity had come into full power. Nor did the people of that time expect the state to extend its activity to these fields.

332. The defense of the Empire was one of the most important tasks of the government. Happily boundaries formed by the Atlantic Ocean in the west and the sand deserts in the south did not require constant watching, like the northern edge of Roman Britain and the frontiers on the Rhine, the Danube, and the Euphrates. These received careful attention. The standing army counted thirty legions of some six thousand men each, a force which, including the auxiliaries and naval troops, never amounted to more than 400,000. The inner provinces, as a rule, needed only a handful of soldiers for police duty. At one time 1200 sufficed to garrison all Gaul, while in the same country there are at present 200,000 French and more than 50,000 Belgian soldiers in time of peace.

The army recruited itself more and more from the frontier provinces in which the legions were stationed. It was a body of hired professional soldiers, who had intense pride in their fighting power, their privileges, and the Roman name. Later on barbarians were admitted in ever increasing numbers. The discipline was severe. In times of peace the soldiers were employed in the building of roads, bridges, aqueducts, and similar works. At the expiration of twenty years of service, the soldier commonly received a grant of land and the rights of citizenship. This helped to mix the many races of the Roman world. Along the frontier, too, cities arose around the stationary camps of the legions.

CONDITION OF THE POPULATION

333. Blessings of Political Unity.—The boundary lines between the many states around the Mediterranean had disappeared. One and the same government protected the traveling Spaniard in Italy, in Syria, in Egypt. The Greek could own property in Gaul and northern Africa. The wonderful system of Roman roads, which was ever being enlarged and perfected, and the navigation upon the Mediterranean Sea, which was now a Roman lake, promoted and encouraged intercourse among all the parts of the Empire. Hence the products of one land were at the disposal of all the others. The manufacturers of some city or district formerly had to cope with all kinds of difficulties to market their goods outside their own land. Now the whole Empire was open to them. Hence an immense traffic flowed ceaselessly between all the provinces.

Glass and paper came from Alexandria; silks, tapestries, morocco leather, from Syria; silverware from Ephesus. The land was better utilized. New cities arose. “Every day,” says the Christian writer Tertullian, “the world becomes more beautiful, more wealthy, more splendid. No comer remains inaccessible. Every spot is the scene of trade. Forests give way to tilled acres. Wild beasts retreat before domestic animals. Everywhere are houses, people, cities.”

334. Industries. — The chief industry was farming, which in most places served local needs. We must think of the city nearly always as being the core of a farming district around it. Only the “grain countries,” as Egypt, many parts of Asia Minor, Sicily, and northern Africa, produced on a large scale for exportation. Unfortunately, the devouring of small farms by rich landlords (§ 259) began to show ominously in the provinces also. Near the great centers of population market gardening yielded an honest livelihood to thousands of industrious men.

In the cities numerous people made their living as weavers, fullers, goldsmiths, shoemakers, etc. In Rome the bakers’ gild listed 254 different shops. There were 2300 places where olive oil was for sale. Above this class were the merchants, architects, bankers, teachers, physicians. We read even of dentists and eye- and-ear specialists. No doubt there were many quacks among the physicians, but the more skilled ones earned enormous incomes. The highest rank was composed of lawyers, great state officials, army officers, and the owners of large estates. Banking was carried on, on almost modern lines. The great amount of business that was going on, and the numerous money transactions, made the bankers’ business very lucrative, though only the richer bankers were looked upon with respect. In all these concerns, large and primitive, however, a considerable part of the work was commonly performed by slaves. Sometimes slaves ran the biggest banking firms in a city.

336. The amount of commerce going on in the Empire has already been indicated. There was also an immense traffic with foreign countries. The Roman trader went where Roman legions never camped. Somehow he penetrated into central Africa and brought ivory, spices, apes, rare marbles. We know that many merchants reaped immense riches by venturesome voyages to India, Ceylon, and the mouths of the Ganges; and that Canton in China received glass and metal wares, amber (from the Baltic), and jewels through Roman traders.

As soon as commerce outgrew local conditions, however, it made necessary a great amount of traveling. Business affairs could on the whole rarely be settled satisfactorily by correspondence, because there existed no general mailing system. (The postal service established by the emperors was strictly confined to government matters.) To get a letter from Lyons to Milan the business man had to wait until some reliable person, who happened to journey to that city, was willing to deliver it. But this chance correspondence did not suffice to carry on brisk business. Personal intercourse was required. Hence a large number of business men, managers, agents, trusted messengers, were constantly on the road.

336. As to refinement and luxuries in the homes of the rich, see § 257. The few indications given there are, however, utterly inadequate for the time we now have under consideration. Pliny the Elder, who died in 79 A.D., was considered moderate

because his daily dinner lasted only three hours. (At the table the Romans, like the Greeks, did not sit but reclined on couches.) The great variety and preciousness of table things and house furniture baffle description.

337. Unity of Feeling. — Most of the Roman lands had been united with the Empire by acts of cruel injustice. But when the people had experienced for some time the blessings of law and order, and been the object of the care of a large-minded administration, they forgot the past and became enthusiastic citizens of the world-wide Empire. Briton, Thracian, Greek, African, and Syrian, all called themselves proudly Romans. It was not a union brought on by force, but by the evident advantages which the Empire bestowed on all its members. The provinces furnished emperors, administrators, prominent men of letters. The schools in the provincial towns vied with those of Rome and often were superior to them. “No matter where we are in the world,” says a Christian writer, “we live as fellow citizens, inclosed within the circuit of one city and grown up at the same domestic hearth. An equal law has made all men equal.”

EDUCATION AND ART

338. Educational institutions of some kind or other were very numerous. The small towns had many elementary schools for the upper and middle classes, in which occasionally boys of the inferior ranks were admitted. Otherwise little was done to dispel the ignorance of the masses. The larger provincial cities possessed higher schools, of which especially those of Spain and Celtic Gaul were famous. To some of these students flocked from the whole Empire. The walls of the classrooms were painted with maps, dates, and lists of facts. The masters were appointed by the local magistrates, with life tenure and good pay, and with exemption from taxation.

In three cities, Rome, Athens, and Alexandria, there existed institutions which we should call universities. The one in Alexandria dated from the time of the Ptolemies (§ 187). Augustus had founded the one at Athens. All either received money from the imperial treasury or possessed endowments, that is, estates, the revenue of which went to these institutions or to certain sections of them. The professors were highly salaried, and were assured a pension for life after twenty years of service. They had the rank of senators. Rome was famous for the study of law, while medicine was a specialty at Alexandria.

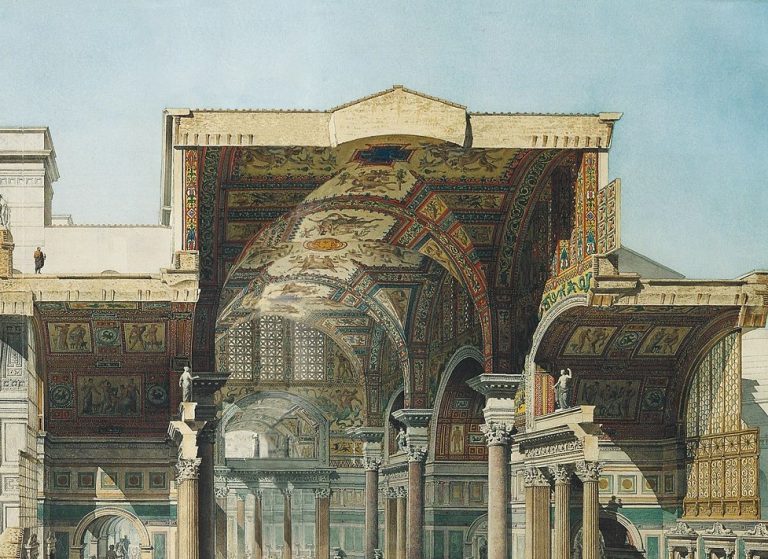

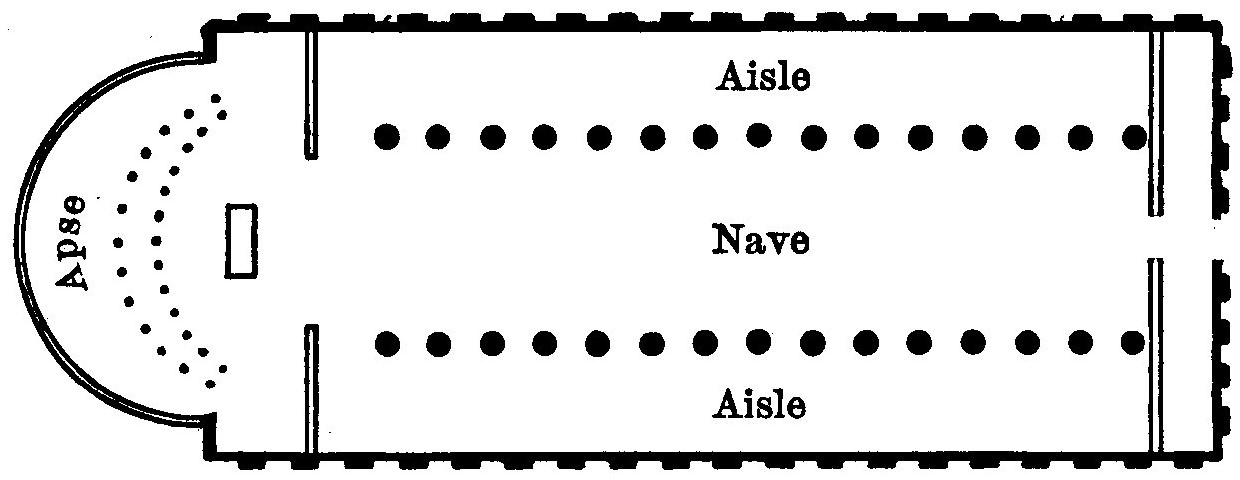

A basilica (see opposite page) built in the fourth century. It has five aisles. The medallions on both sides are pictures of the popes, beginning with St. Peter.

339. Arts. — The Romans adopted the arts of the Hellenistic world. They bought the products of Alexandrian or Greek sculptors and painters, or these themselves came to the West and found ample employment in the palaces of the rich. An endless number of the most perfect productions in gold and silver, in marble and terra cotta are constantly being unearthed in the ruins of all the once Roman countries. There are all kinds of household things, toilet articles, cups, and other utensils for use at banquets; lamps, chandeliers, vases, and statues and statuettes which ornamented the houses and halls; imperial and private seals executed with wonderful exactness on small stones or in metal.

The Basilicas were halls serving for the sessions of law courts, public meetings, and similar purposes. They commonly were oblong in shape, and divided lengthwise into a wide central “nave” and two (or more) “aisles.” At one end there was usually a raised semicircular “apse” with seats for the judges. Later on the Christians found this kind of building admirably adapted for their worship. For centuries nearly all the churches were built on this general plan, which eventually grew into the ground plan of the medieval churches.

340. In architecture, too, the Romans followed the lead of the Hellenistic East. Their temples of this period look much like those built in Hellas (§§ 147 and 329). Yet they introduced some new elements, especially the arch (§ 229). The use of the arch is very prominent in structures of a utilitarian character, such as the aqueducts, which provided the large cities with good water. Twelve aqueducts, four of which are still in use, poured daily more than three hundred million gallons into the city of Rome. The baths, in the larger cities, commonly were grand buildings, providing for cold and warm baths. The magnificent baths erected by emperors in Rome contained also large halls for recreation, lecture rooms, and libraries. There were moreover the theaters; the circuses for horse races and other contests ; the amphitheaters (all-around theaters) chiefly for the fights between animals or gladiators; numerous structures for government purposes; and finally an endless number of large and small temples. We must also mention the many triumphal arches and memorial columns put up in honor of victorious emperors and generals, which by their inscriptions and pictorial representations contribute greatly to historical knowledge. A building peculiar to this time was the basilica, a public hall for the sessions of courts of justice, and for various kinds of business. The basilica became the forerunner of the later Christian churches.

In general the Roman architects of this period built on grander dimensions than the Greeks. Their knowledge of the arch enabled them to cover passageways and even wide halls, if they chose, with vaulted ceilings. They liked display and profusiveness in the ornamental parts. They used the arch, too, for ornamentation, an instance of which is to be seen on the outside of the Coliseum (see page 239). Among the columns they preferred the Corinthian (§ 110), and often embellished even that by additional flourishes. They beautified the floors of temples and palaces and villas, and in rarer cases also the walls, with a profusion of mosaics. They used relief work (§ 22, note) very extensively on temples and other public buildings. The buildings, as a rule, were models of a noble taste. Many of them combined successfully the majestic massiveness of the Egyptian structure with the elegance and sometimes even the loveliness of the creations of the Hellenes.

341. Literature. — As remarked in § 229, Roman literature developed rather late. Its greatest time was that of the last period of the republic and the reign of Augustus. There were books and plays, the latter mostly translations or adaptations or imitations of Greek originals before the year 100 B.C. The historian Polybius died in 122 B.C. But the Roman literature, which has ever held the admiration of the following centuries, began with Cicero (106-43 B.C.) (§ 289). Cicero was prominent as an orator — second only to Demosthenes; great as a philosopher, though he did not produce a philosophical system of his own; and is generally renowned as the best prose writer of the Latin language. His time, the period of Pompey and Caesar, was favorable to the development of oratory, and he was by no means the only great public speaker in Rome. (Caesar himself figured next to him in the opinion of contemporaries, but we possess none of Caesar’s speeches.) By one of his speeches Cicero procured for Pompey, with whom he sided, the appointment as general for the war against Mithridates, §285. The fact that fifty-seven of his orations have survived and have been admired and studied for two thousand years is evidence of their excellence. We also possess no less than thirteen philosophical works by his pen, and 864 letters — all of which show his perfect mastery of the Latin tongue. This was, however, a time of great literary productivity, and many other names shine brilliantly in the heaven of Roman literature during the following centuries. Livy, the historian, was a contemporary of Augustus. Tacitus wrote history during the time of the Flavian emperors.

Under Augustus Rome produced her greatest poets: Horace, unrivaled in lyric poetry; Virgil, who, besides other works, produced the Aeneid, a kind of Roman Iliad (§ 76); and Ovid, known for his easy-flowing poems on various subjects. These, too, are surrounded and followed by a large number of poets, who though not their equals yet produced a great variety of commendable works.

During the second half of the first century also the books of the New Testament were written, which together with the Old Testament form the most important of all productions of the world’s literature. Their real author is God Himself, and their purpose is infinitely higher than that of all literary compositions of the most brilliant human authors.

Of writers on natural sciences we must mention Pliny the Elder, who compiled an exhaustive Natural History, in which he summarizes whatever was known to the ancients in zoology, botany, mineralogy, physics, geography, astronomy, etc. Pliny perished while climbing Mount Vesuvius during its eruption (§ 321). He was the only Roman that wrote on the sciences, which were cultivated extensively in the East. The Alexandrian Ptolemy, great as mathematician, geographer, and astronomer, after much study fixed the astronomical system which dominated the world until Copernicus.

Besides Cicero, Seneca, the teacher of Nero, is known as a philosophical writer. The emperor Marcus Aurelius, too, wrote on philosophy. These based their teachings upon the tenets of Stoicism (§ 189), which indeed found many adherents among the educated classes of Rome. Rome produced no new philosophical system of her own.

MORALS

342. Unfortunately the picture of Roman morals has many more dark colors than bright ones. The Greeks had added to their own depravity the customs of the Orient. The facility of intercommunication furnished by the Roman Empire helped to spread both through the lands of the Mediterranean. Though Rome never officially accepted polygamy, as the East did, the family tie became in wide circles a thing of the past. Adultery was almost a matter of fashion. Divorces, always permitted by the Roman law, became dreadfully frequent. Many preferred criminal celibacy to honorable marriage. It was by no means rare that fathers made use of the barbarous “right” of exposing their children rather than rearing them. Destruction of the blossoming life was in general vogue. Laws which imposed a special tax on bachelors, and gave privileges to every father of three children, did not have the desired effect.

343. The gladiatorial shows greatly fostered this contempt for human life (§ 261). These brutalizing performances had increased enormously in number and size. Dozens of gladiators fought for life with wild beasts or with one another. On some occasions regular armies of hundreds of them displayed before a rejoicing crowd all the horrors of the battle field. This was the choice delight, not only of the rabble, but of the most educated society, including the most refined ladies. Even the Vestal Virgins (§ 196) witnessed these orgies of cruelty and blood.

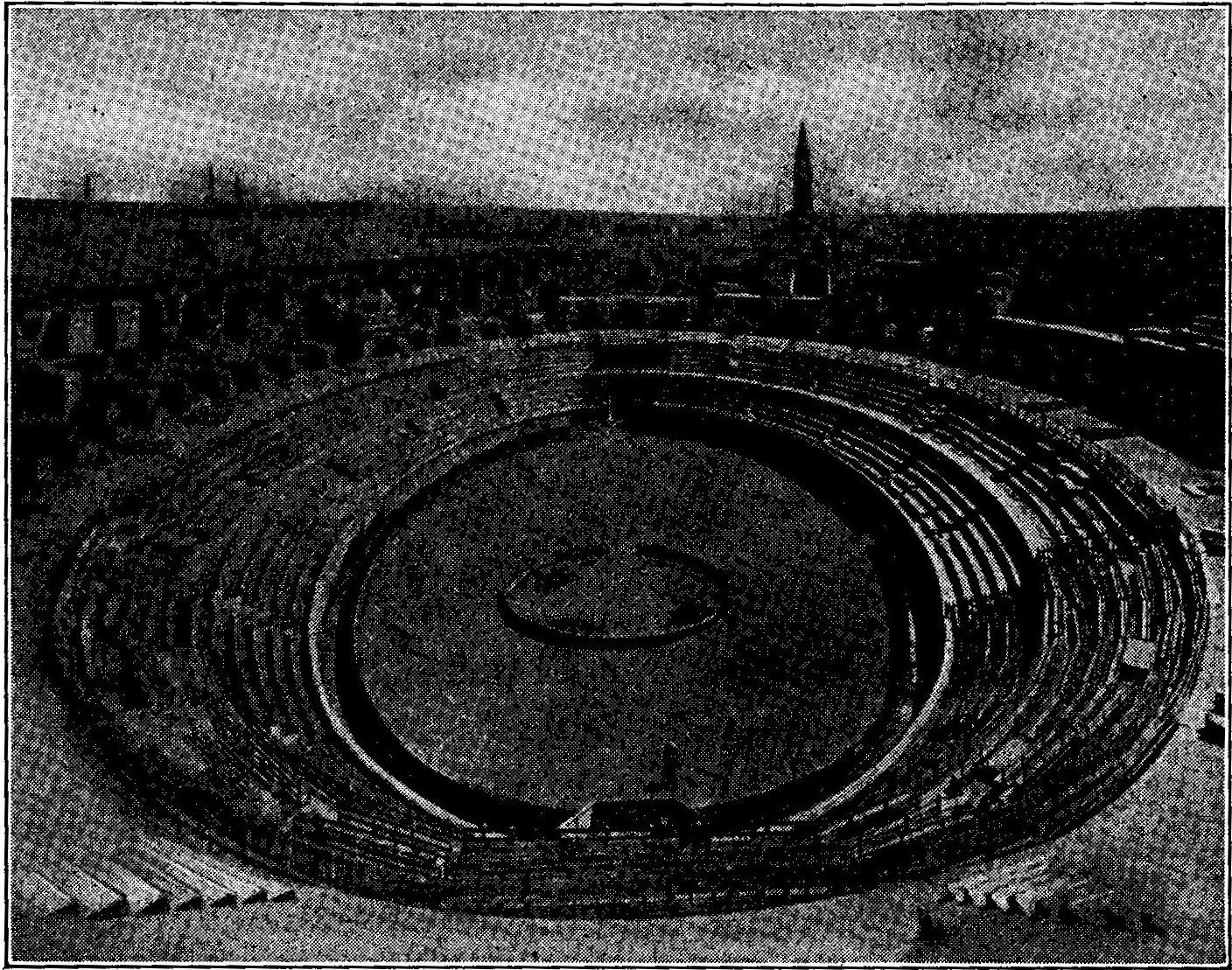

The circuses were for chariot races. The seats were arranged as in the theaters and amphitheaters. Along the central line stretched the “spine,” distinguished by ornamental columns.

344. Slavery, too, was a most fruitful source of moral and other evils. The cruelty with which slaves were generally treated (§ 262), the heartlessness with which old and disabled slaves were left to die, increased the contempt for human life. The abyss of vice that is indicated by the complete dependence of this unfortunate class upon all the whims and even passions of the master and mistress cannot be described. Slavery, moreover, tended to crowd out the free labor of the poorer classes, both in town and country, and this despite some laudable efforts of the government to prevent it.

345. The position of women improved in that the customs of the Empire practically did away with the status of wives as legally the slaves of their husbands (§ 199). Women now engaged in various trades. They became women’s physicians. Many of them took to writing, though none of their productions have come down to our own times. They too were subject to the baneful influence which Roman slavery had upon masters and mistresses (their refined cruelty toward their female slaves was well known); their characters and minds were degraded by the bloody and lascivious shows; and they had before them the unspeakably bad example of the men, including their own husbands (if they had any). Thus they became largely estranged from their natural position as queens of domestic society, and contributed their ample share to the general demoralization.

One of the smaller buildings of this kind. The amphitheaters (all-around-theaters”) served chiefly for gladiatorial shows (§343), which took place in the oblong arena in the center. Here, too, Christians were thrown to the lions. This amphitheater is 440 feet long, 336 feet wide, and 70 feet high. The arena measures 227 by 126 ½ feet. The stone seats, rising in tiers, accommodated 24,000 spectators. The structure is kept in repair and, as the benches in the foreground show, is used for public entertainments.

346. Relieving features, however, are not entirely lacking. We find instances of genuine friendship, of true affection among the members of families, of generosity toward the needy. We hear of homes for poor children and for orphan girls. We know that on one occasion the rich of Rome opened their purses for the relief of sufferers. Laws were passed to give some protection to the slaves. Money donations made possible the institution of libraries for the public. In acting thus unselfishly men may have been prompted by that noble delight which characters not wholly depraved feel in works of kindness. Or they may have been influenced by the Stoics’ doctrine (§ 189) of a general brotherhood of men. Or they may have adopted some of the principles of the Christian religion, which, though still persecuted, appealed to many by its practice of charity. But in spite of such isolated examples to the contrary, the predominating character of the Roman world was that of insatiable, cold-blooded avarice, unbounded pride, and a voluptuousness which brooked no restriction of right or decency.

CONCLUSION

The Roman monarchy no doubt achieved great things. For defending vast territories from the horrors of war; for preserving order and security in the interior; for promoting material welfare, and the spread of civilization among its countless citizens: it deserves our admiration. Never again did the same lands enjoy such an unbroken period of rest as was granted to them by the Roman Peace. But if one of the most sacred duties of the state is to prevent the impoverishment of the most numerous classes and protect them against being overreached by the rich, the Empire failed. The poor became ever poorer, and ever more numerous, while the rich grew fewer and had every opportunity to increase their possessions to a fabulous extent. The Empire failed, too, in stopping the flood of immorality, which like a torrent of destruction rolled its waves into all stations of life and into all the localities, which otherwise rested so securely under the wings of the Roman eagles. The Roman Peace moreover contributed a very great share toward making the population less warlike. Thus in many ways these glorious centuries prepared the later downfall of the Empire, though that catastrophe was still several centuries away.