The following is an excerpt (pages 317-333) from Ancient and Medieval History (1946) by Francis S. Betten, S.J. Although some information may be outdated, the Catholic historical perspective it provides remains pertinent. Use the link at the bottom of post to read the previous/following pages. Use the Search box above to find specific topics or browse using the Resources tab above.

CHAPTER XXXI

THE ALLIANCE OF THE PAPACY AND THE FRANKS

By the conversion of Clovis to the Catholic religion, the Franks entered into a close union with the Church (§415). This union was to become an official alliance by the coronation of a Frankish king as Roman Emperor. Several steps led up to this goal. The brilliant defense of western Christianity against the forces of Islam may be considered as one such step. Two more were to follow, namely, the accession of a new line of kings, and the establishment of the Papal States.

THE NEW FRANKISH DYNASTY

425. Death of Charles Martel. — Shortly after the victory at Tours the Do-nothing king died. Charles Martel did not venture to take the title of king, but neither did he place any Merowingian on the throne. With the consent of the nobles he divided the dignity of mayor of the palace between his two sons, Karlman and Pippin “the Short.” But these, feeling less secure than their victorious father, again raised a Merowingian king, Childeric III, and ruled in his name. Karlman, however, soon retired into a monastery, as indeed many princes of that and later ages have done. Pippin the Short was thus left sole Mayor of the entire kingdom.

426. The Work of St. Boniface. — It was during the time of Charles Martel, Karlman, and Pippin, and with their hearty support, that St. Boniface (the name was given him by the Pope, and means Benefactor), the Anglo-Saxon monk, began and finished the systematic conversion of the eastern part of the Frankish kingdom, which was later on to develop into modern Germany.

Christianity had been planted in many localities of those provinces, notably in the districts near the Alps, by zealous Irishmen and Franks. There were, however, no bishops to provide priests for vacant stations and combat corruption, ignorance, and heresies. Wide regions, moreover, had never heard the voice of the missionary. St. Boniface under incredible hardships converted the numerous heathens. In constant intercourse with Rome by visits and letters, he established bishoprics with himself as archbishop. This made him the apostle of Germany. As papal legate for all the countries north of the Alps he also undertook, chiefly by a long series of councils, a reformation of the Frankish Church in morals, discipline, and doctrine. Charles Martel and much more Karlman and Pippin gave him their powerful protection.

During the seventh century the intercourse between Rome and the Frankish kingdom had been reduced to a minimum. St. Boniface now for nearly forty years referred everything of moment to Rome, conducted his affairs according to instructions from Rome, and emphasized in all his transactions with rulers and nobles the absolute necessity of keeping in close touch with the center of Christian unity. This brought about a complete change. The whole kingdom recognized most vividly the position and power of the Successor of St. Peter, the common Father of Christendom.

427. Accession of the Carolingians. — Pippin the Short meanwhile thought of setting aside the nominal king and assuming the royal dignity himself. Such a step would enable him to rule with greater power and efficiency. Nor was it beyond the competency of the nation to remove an unfit ruler. This was a strictly domestic affair; but an embassy crossed the Alps to far-off Rome to lay the matter before the Holy Father. Pope Zachary answered, it was better that he should be king who was actually performing the king’s duties. Thereupon Pippin the Short was unanimously chosen king by the Franks. St. Boniface, by order of the Pope, anointed the first king of the Carolingian line, 752 A.D. Childeric, the last Merowingian king, ended his days in a monastery. “An important revolution of the greatest benefit for Church and State, one of the most momentous events in history, was thus brought about without the slightest disorder.”

FOUNDATION OF THE PAPAL STATES

428. Rome and the Popes. — Constantine the Great besides giving liberty to the Church donated large possessions to the Apostolic See and other ecclesiastical institutions. His example was followed by others. Eventually the pope became the richest landowner in Italy, a fact which enabled him to be, during the stormy period of the barbarian invasions, the benefactor of the poor and distressed throughout the whole world. Various emperors, moreover, bestowed on the popes regular governmental powers, such as the administration of the existing poor laws. All this helped to make the pope in the course of time the most important personage in Italy, particularly in Rome — the more so because, after the foundation of Constantinople, no emperor ever made the ancient capital his permanent residence. “Old Rome” was despised by the emperors as an unimportant provincial town. Their energy was required for the defense of the eastern frontier and was often squandered in domestic revolutions and religious disputes. It was the popes that kept up order in Rome and the little district which surrounded it (§ 413). They even collected the taxes exacted by the greedy ruler on the Bosphorus.

The Roman as well as the Ravennese territory was suffering from the persistent attacks of the Lombards. This Teutonic nation, even after its conversion to Catholicism, retained much of its primitive ferocity. The conquest of a city spelled certain ruin for its inhabitants. The emperor confined himself to writing encouraging letters and intrusting the popes with the defense of the country by arms, or by diplomatic missions to the Lombard court. If the helpless territories had not been swallowed up in 750 A.D., it was exclusively due to the popes.

More and more were the people drawn towards the actual ruler of their little “ state.” The district was looked upon as the property of St. Peter and his successors. The pope certainly would have violated no right, had he renounced an allegiance which had long been forfeited by powerless, careless, or incapable emperors.

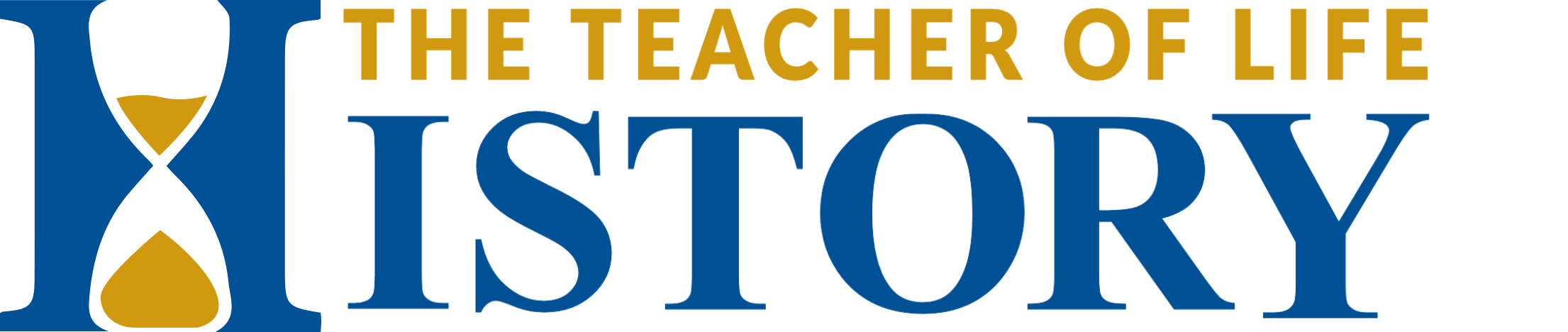

29. Foundations of the Papal States. — About 750 A.D. the attacks of the Lombards were renewed with increased violence. Letter upon letter went to Constantinople, and as usual nothing came back but letters or messengers offering words of encouragement with neither money nor army. Under these circumstances, Pope Stephen III finally resolved to apply for aid to the new king of the Franks, Pippin the Short. He himself made the journey across the Alps and was received with the greatest honor by the nation and their monarch. In a solemn assembly king and nobles swore that they would not fight against the Lombards, hitherto their friends, to reconquer territory either for themselves or for the emperor whose claims had lapsed, but that they were ready to vindicate with their swords the rights of the Church, St. Peter, and the Holy See.

The Franks crossed the Alps, and the Lombard king Aistulf gave up his conquests. Pippin might have kept these provinces for himself. He was able to defend and take care of them. But such was not his intention. He “restored them to St. Peter and his successors, to be possessed by them forever.” In 756 A.D. the district of Rome together with that of Ravenna became the Papal States. Pope Stephen III, now real sovereign, gave Pippin the title of Patrician of the Romans, which made him the secular protector of the new papal monarchy.

430. Importance of the Papal States. — In Rome, as a matter of fact, the popes had ever been either persecuted and prisoners, or the most prominent personages. Though at all times desirable, a full sovereignty was less needed for them as long as nearly the whole Church was confined to the Roman Empire. It would be different in the times to come. “By a special dispensation of Divine Providence,” says Pope Pius IX, “the civil sovereignty came to the Roman Pontiff. If he were subject to another monarch’s rule, he could never, in performing the duties of his Apostolic office, keep himself free from the influence of his sovereign, who might even fall away from the faith or wage war with another power.”

The Papal States are for the Church what the District of Columbia is for the United States. They are not the private property of the popes any more than the White House is the property of the President or the parochial residences the property of our parish priests.

The territorial independence of the Papacy is a necessary element in the life of the Middle Ages. This evident fact cannot always be referred to expressly in this textbook. Let the student himself ask the question, whether, on certain occasions, the pope would have acted as he did had he been the real subject of, say, France, or Germany, or England.

CHARLEMAGNE: HIS WARS AND HIS EMPIRE

CHARLEMAGNE AND HIS WARS

431. Charlemagne the Man. — In 768 Pippin, King of the Franks, was succeeded by his son Karl. This prince is known in history as Charlemagne. No doubt he was one of the most remarkable men that ever lived, and his work has profoundly influenced all later history. His friend and secretary, Einhard (Eginhard), describes him as a full-blooded German, with yellow hair, fair skin, and large, keen, blue eyes. He was simple in habits, temperate in eating and more so in drinking. He usually wore the ordinary dress of the Frankish noble, with a sword at his side and a blue cloak flung over his shoulders. But he was also a lover of Roman culture, and spared no efforts to preserve and extend it among his people.

He handled Latin as readily as his Frankish tongue, and understood Greek when it was spoken. He liked books. The City of God, by St. Augustine, was his favorite reading (§ 380). Frequently someone had to read to him during his meals. He made desperate attempts to learn also how to write, but was never able to do much more than sign his name. For the times, however, he was an educated man, and most willing to appreciate the learning of others. He gathered learned men around him from distant lands and delighted in their conversation. After his death, legend magnified and mystified his fame in all the countries that had been under his sway.

432. Character of Charlemagne’s Wars. — The Frankish state was still in peril, from Mohammedanism on one side, and still more from barbarism on the other. His grandfather and father had checked the invasion. But under the vigorous new prince the Franks took the aggressive and rolled back the peril on both sides. His reign of nearly fifty years (768-814) was filled with ceaseless warfare, oftentimes two or more great campaigns to a season. At first glimpse, therefore, Charlemagne stands forth a warlike figure, like Caesar and Alexander. Like them he supported by arms the extension of the area of civilized life. But very unlike them, he conceived of no civilization except that imparted by Christianity. In fact, the protection and spread of Christianity he considered as his chief aim from the beginning of his long reign.

He did not war for glory or gain as such. The greater part of his time and efforts was given to interior organization and government. Charles was not so much a fighter as a statesman and ruler. His wars had a twofold political result: (a) the enlargement of the Frankish state, and (b) the establishment of tributary border states.

433. The Enlargement of the Realm. Winning of the Saxon Lands. — The heathen Saxons still held the wilderness between the Rhine and the Elbe, near the North Sea. They were constantly harassing the Frankish dominions by devastating raids. Missionaries could never penetrate into the land. For Charles the war against them was a necessity. But it proved a desperate enterprise. Nine times, after they seemed subdued, the Saxons shook off his yoke, massacred the Frankish garrisons, and returned to the abominations of paganism with its human sacrifices.

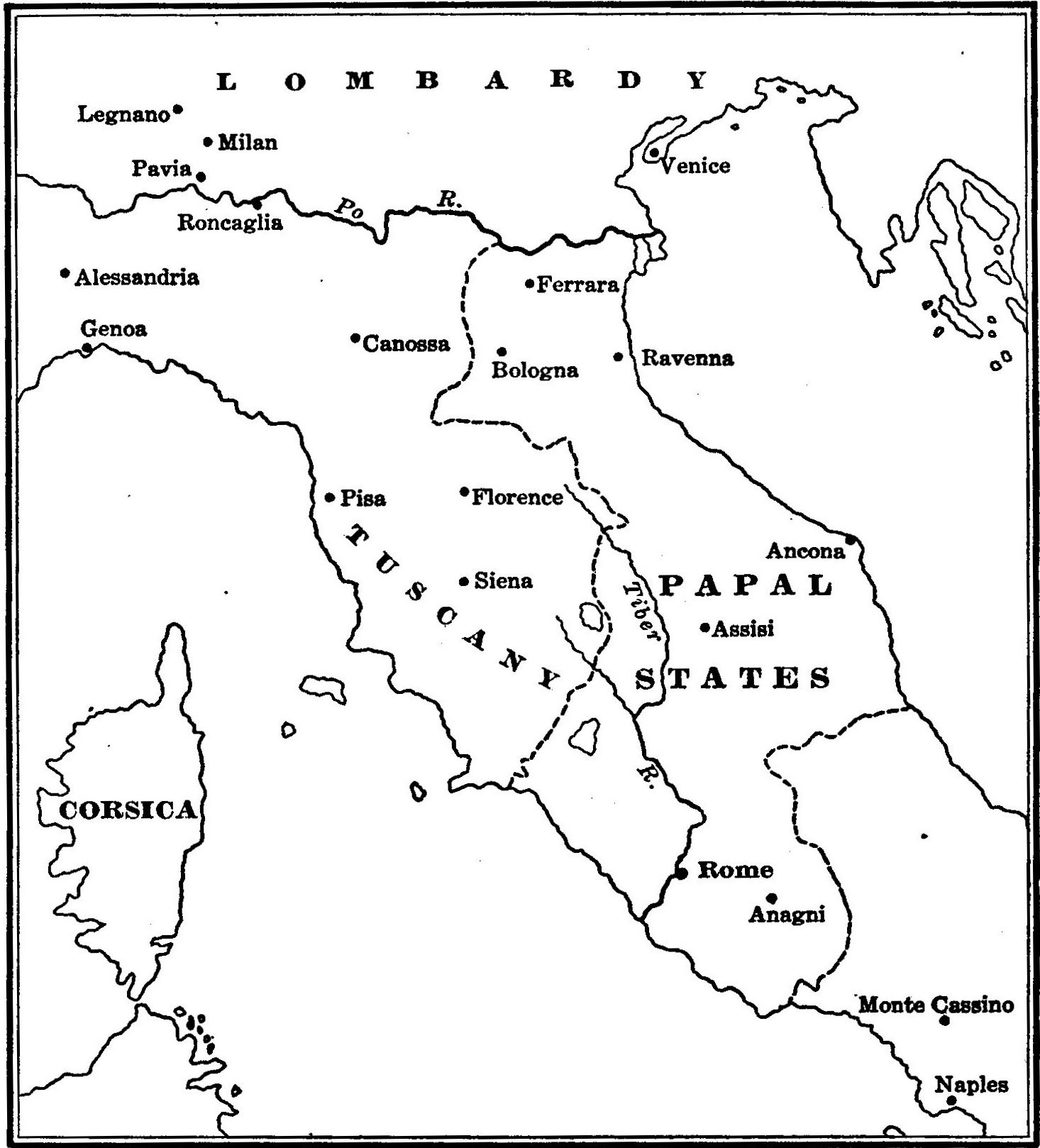

This is the nearest approach to a likeness of the greatest Franks. The inscription is much abbreviated: XPE PROTÉGÉ CAROLUM REGE(M) FRANC(O)R(UM), “Christ protect Charles the king of the Franks.” See legend of illustration on p. 235. The cross stands for an X. (The so-called) pictures of Charlemagne in many books are purely imaginative, by artists of later centuries.)

Unfortunately Charles’ methods were not above reproach. Contrary to the spirit of Christianity he forced the Saxons to be baptized. It is a blot on his name, too, that he executed after one rising forty-five hundred men (a number doubted by good historians). The rebels, however, had been condemned by their own chiefs. The genuine conversion of the Saxon leader Widukind was a great step toward final submission.

These wars were the most fruitful of the whole century. The Saxon country came to be covered with churches and monasteries and the schools inseparable from them. The Saxons became fervent Christians and proved loyal subjects to their stern conqueror. This conversion and the establishment of bishoprics in Saxony completed the work of St. Boniface for Germany. Christian civilization now extended to the Elbe. The country thus gained was destined to play an influential part in the formation of medieval Germany.

In other campaigns Charles thrust back the Saracens in Spain as far as the Ebro and established there the Spanish March. The last Lombard king, Desiderius, quarreled with the Pope. After fruitless negotiations Charles marched into Italy, confirmed Pippin’s grant to the Apostolic See, conquered the kingdom of Lombardy, sent Desiderius to a monastery, and with the partial consent of the nation proclaimed himself King of the Lombards. He also reduced Bavaria, which had never been a secure possession, deposed its duke, and incorporated it into the Frankish state. With it went the countries between Bavaria and the northern end of the Adriatic Sea.

Thus all the surviving Germanic peoples on the continent of Europe, Lombards, Burgundians, Bavarians, Alemannians, Saxons, Frisians, Franks, and part of the Visigoths were united in one Christian state. The population, except in the northeast, was overwhelmingly Roman, notably Celto-Roman, while the rule was in Teutonic hands. This unity seems to have been the aim of Charlemagne.

It is worthy of notice that the small Teutonic states outside his realm — in Denmark, Scandinavia, and England — recognized in some vague terms an overlordship in the ruler of the continent.

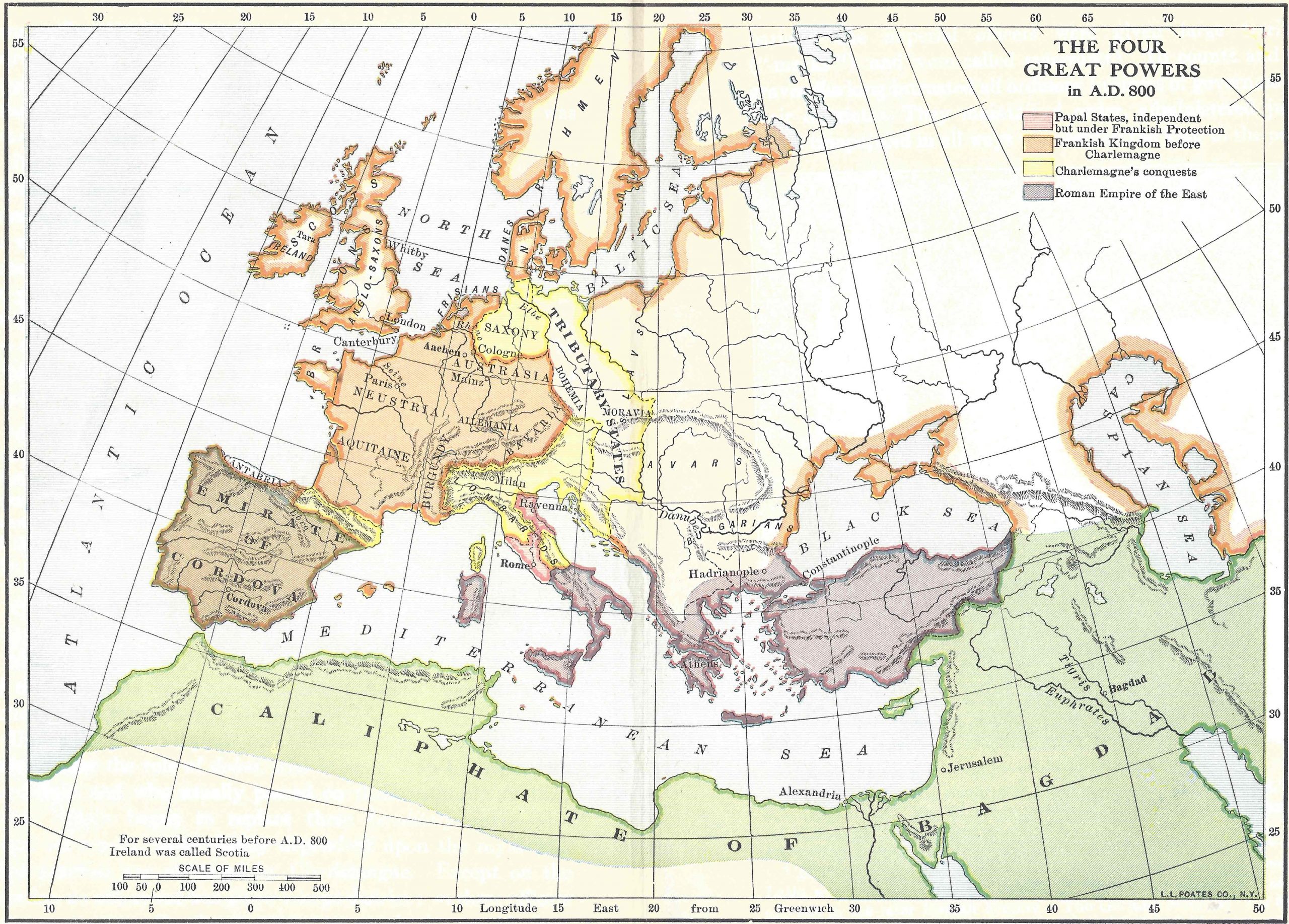

434. The Tributary States. — Beyond the German territory there stretched away indefinitely the Slavs and Avars, who from time to time hurled themselves against the barriers of civilization, as in old Roman days. In the closing part of his reign, Charlemagne attacked barbarism in its own strongholds. These long wars were really defensive in character. Gradually the first line of the people beyond the Elbe and Danube (including modern Bohemia and Moravia) was reduced to tributary states. They were intended to serve as buffers against their untamed brethren farther east. (Notice the acquisitions made by Charlemagne and the extent of his empire on the map following page 328.)

But the event which more than anything else gave to Charlemagne his place in history is the revival of the Roman Empire in the West.

CHARLEMAGNE AND HIS EMPIRE

435. Possibility of the Revival. — In the West of Europe the idea of an emperor was not forgotten (§§ 371, 393, 413). The nations, Teutonic as well as Roman, desired to see an emperor rise again who would combine imperial power with an imperial title, who would, according to the notion cherished since Constantine, be a defender of the Church, a protector of right and justice. There was now a ruler who lacked none of all the requisites but the title. Some exchange of thought on this subject had evidently taken place between the Pope and Charlemagne, at least in some general way. A renewal of this sacred dignity was of advantage to both. The magic of the name would enormously increase the king’s authority over the many nationalities of his realm, and the Pope would gain a greater claim to the active assistance of the Frankish monarch. The only one who, according to the spirit of the time, could take the initiative and act as the spokesman of the nations was the Pope. An emperor sanctioned and crowned by the Head of all Christendom would meet with a general and unbounded enthusiasm.

436. Coronation of Charlemagne. — In 799 A.D. a band of Roman nobles, probably relying on the support of a Lombard and Byzantine faction in Italy, attacked Pope St. Leo III in a procession, and only with great difficulty could he save himself by flight. Like Stephen III he went in person across the Alps, and obtained from the king the promise of his assistance. The following year saw Charlemagne in Rome, where he took vigorous measures for the future safety of the Holy Father. Then, on Christmas, when Charles was kneeling in St. Peter’s Church to hear Mass, Pope Leo III approached him, placed a golden crown upon his head, and greeted him with the words, “Long life and victory to Charles, the most pious Augustus, crowned of God, the great and peace-giving Emperor of the Romans.” The cry was repeated in the church and reechoed by the crowds outside. Christmas Day of the year 800 is one of the most memorable dates in the history of Europe. It is the birthday of the Holy Roman Empire.

437. Relation of the Emperor to the Pope and to Other Rulers. — By his elevation the emperor gained neither any new territory nor the right of interfering in the interior affairs of any other state. Nor did he become the sovereign of the Papal States. On the contrary, it was one of the obligations of his office to guarantee these possessions to the incumbent of the Holy See. Only when requested by the pope was he allowed to exercise jurisdiction within them. Neither did his position make him a subject of the Pope in temporal matters. But the new dignity endowed him with a moral power which no feat of arms or successful conquests could have given him. Over other Christian princes, should there be any, the emperor would possess a primacy of honor, and the right of summoning them to his assistance in any enterprise undertaken for the welfare of the Church. Papacy and Empire were to stand side by side, each supreme in its own sphere, the emperor being ever ready to support with physical force the spiritual government of the pope and to defend all the interests of the Church of God on earth.

The great act of 800 A.D. in St. Peter’s Basilica was the beginning of that intimate union between Church and State which, in spite of many shortcomings, must ever be considered as the nearest realization of the true ideal relation between the two which the world has ever known. The medieval emperor stood essentially higher than any other ruler; he was endowed with a sacred character; only one prince might rightfully call himself Emperor, and he only after being crowned by the head of the Church in Rome. The Papacy and the Holy Roman Empire were the two centers around which moved events of the greatest importance in European history.

All these attributes of the imperial dignity were rather acknowledged instinctively by the contemporaries of Charlemagne than formally expressed. The very designation of “Holy Roman Empire” was coined later. By his tact Charlemagne soon overcame the sensitiveness of the Byzantine emperors, and before long was addressed by them as “Emperor and King.”

LIFE IN CHARLEMAGNE’S EMPIRE

438. Economic Conditions. — We must not think that the glory and prosperity of the old Empire had been restored with its name. To accomplish that was to be the work of centuries more. In 800 the West was ignorant and poor. There was barbarism in the most civilized society. Roads had fallen into neglect; brigands infested them; and there was little communication between one district and another. Money was scarce. Almost the only industry was agriculture.

Perhaps we can see this condition best by looking at the revenues of Charlemagne himself. Great and powerful as he was, he was always pinched for money. There were no taxes, as we understand the word, partly because there was not enough money with which to pay them. Payment was made by service in person. The common freemen paid by serving in the ranks of the army, the nobles by serving with their followers, and also by acting, without salary, as officers in the government. The chief support of the king’s treasury came from the royal farms scattered through the realm.

The king and court often traveled from farm to farm to consume the produce upon the spot. Charlemagne took the most minute care that his farms should be well tilled, and that each one should pay him every egg and vegetable due. For the management of his estates he drew up regulations, from which we learn much about the conditions of the times. (Davis’s Readings, II, No. 149; or Ogg’s Source Book, No. 18.)

439. The government of Charlemagne’s empire was rude and simple, but suited to the conditions of the age.

Five features deserve attention: the counts; the watching of the counts by the missi dominici; the king’s own marvelous activity; the capitularies; and Mayfields.

Under the Merowingians, large fragments of the kingdom had fallen under the rule of dukes, who became almost independent sovereigns and who usually passed on their authority to their sons. Pippin began to replace these hereditary dukes with appointed counts, more closely dependent upon the royal will. This practice was extended by Charlemagne. Except on the frontier, no one count was given a large district; so these officers were numerous. On the frontiers, to watch the outside barbarians, the imperial officers were given large territories (“marks”), and were called margraves. To counts and margraves the king intrusted all ordinary business of government for their districts. They maintained order, administered justice, levied troops, and in all ways represented the king to the people.

THE MINSTER OF AACHEN

The octagon in the center was Charlemagne’s “palace chapel.” Pope Leo III sent rare marble columns from Italy for its construction. The other parts are of later date.

To keep the counts in order, Charlemagne sent out the missi dominici (“king’s messengers”), to examine the administration of the counts, to correct injustice, hold popular assemblies, and report all to the king.

This simple system worked wonderfully well in Charlemagne’s lifetime, largely because of his own marvelous activity. Despite the terrible conditions of the roads, and the other hardships of travel in those times, the king was constantly on the move, journeying from end to end of his vast dominions and attending unweariedly to its wants. No commercial traveler of to-day travels more faithfully, and none dreams of meeting such hardships.

With the help of his advisers, the king drew up collections of laws to suit the needs of his people. These collections are known as capitularies.

To keep in closer touch with popular feeling in all parts of the kingdom, Charlemagne made use of the old Teutonic assemblies, which were held chiefly in May. All freemen could attend. Sometimes, especially when war was to be decided upon, this “Mayfield” gathering comprised the bulk of the men of the Frankish nation. At other times it was made up only of the great nobles and churchmen. To these assemblies the capitularies were read; but the assembly was not itself a legislature. Lawmaking was in the hands of the king. At the most, the assemblies could bring to bear upon him mildly the force of public opinion.

440. Education. — One of Charlemagne’s greatest merits is the encouragement he gave to education. There existed in places all over his empire monasteries with schools attached to them. These he promoted in every way possible, and he urged other monasteries to open new ones. He also insisted that there should be a school in every episcopal city. At Aachen, where he resided most frequently, he established the “Palace School,” of which he himself was a pupil. He induced learned men from Ireland and England to come and devote themselves to the task of teaching in his lands. He won

for his Palace School the famous Anglo-Saxon Alcuin of York, whose expert advice he ever followed in fostering education in his wide empire. He tried to prevail on his nobles, too, to send their children to the new or old schools. Numerous new copies of Holy Writ, Roman and Greek classical authors, biographies, chronicles, and works of secular history were produced, or similar works composed. The large number of learned men who lived and worked and taught in the period after his death was the fruit of his untiring efforts in favor of education.

441. The Place of Charlemagne in History. — Charlemagne restored order to Europe, at least for his lifetime. It is true he was ahead of his age; and after his death his great design in many regards broke to pieces. But the imperial idea to which he had given new life and new meaning was to be for ages the inspiration of the best minds as they strove against the forces of anarchy in behalf of order, peace, and progress.

Charlemagne stands for five great movements:

(а) He expanded the area of Christianity and of civilization.

(b) He created one great Romano-Teutonic state.

(c) As the outward form of this state he revived the Roman Empire in the West.

(d) He brought about a revival of education and learning.

(e) He assisted in securing for the Papacy that independence which it needed to develop its divine resources.

Looking at his work as a whole we may say he wrought wisely and successfully to combine the best elements into a new Christian civilization. Charlemagne stands out as the greatest political figure of a thousand years.

SUMMARY OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF EUROPEAN SOCIETY

During the first part of the Middle Ages the various streams of influence coming from Christianity, the Roman Empire, and the Teutons had run together. The foundations of a new European society with new institutions were laid. It is well to point out in detail what each of the several factors contributed.

442. Christianity (a) restored the worship of the One True God “Who made heaven and earth,” and with it gave back to mankind the safest guarantee of welfare and civilization.

(b) It consequently inculcated the true notion of human life and liberty, thus rescuing the rights of slaves, children, and women.

(c) It secured the future of the human race by reinstating and elevating matrimony.

(d) It furnished the correct notion of the dignity of the lowly and their occupations.

(e) It placed before the eyes of the world a spotless ideal of virtue, the God-Man Jesus Christ, and his immaculate mother Mary.

(f) It established a religion which satisfies the human intellect as well as the human will and heart.

(g) It was itself a world-wide organization, strong enough to foster in its bosom all the rising institutions, and at the same time bringing home the fact of the unity of the human race and the brotherhood of men.

443. The contributions of the Roman Empire were partly those of the population, partly those of the political organization.

(1) The population contributed:

(a) The intellectual and material civilization of ancient

Greece, together with the Oriental inheritance, but all this modified by the Roman genius.

(b) A universal language with its literary treasures, which

even after losing its hold on the common people was to remain the vehicle of educated thought for the next thousand years.

(2) The political organization contributed:

(а) The idea and machinery of centralized government.

(b) Municipal institutions.

(c) Roman law.

(d) The idea of a ONE secular authority as the secular center

and head of the civilized world.

444. The Teutons contributed:

(a) Themselves.

(b) A new sense of the value of the individual as opposed to

that of the state. This idea was extended, rectified, and hallowed by Christianity.

(c) Loyalty to a lord, as contrasted with loyalty to the state.

(d) A new chance for democracy.

(e) A new impetus to the development of law. Teutonic law was crude and adapted to simple conditions. Yet it exercised a wholesome influence on the later codification of the Roman law which formed the basis of legislation in after centuries.

It was in consequence of this manifold inheritance, which fell to it in greater richness, that the West, though saving much less of the actual civilization of former times, contained more possibility for growth than the East. Personal liberty and local enterprise were not stifled. Conditions developed which were to safeguard the Church against becoming the slave of the secular power. The fact that the greatest of religious forces, the Papacy, had its seat in the West no doubt was also of immense moment.