The following is an excerpt (pages 334-353) from Ancient and Medieval History (1944) by Francis S. Betten, S.J. Although some information may be outdated, the Catholic historical perspective it provides remains pertinent. Use the link at the bottom of post to read the previous/following pages. Use the Search box above to find specific topics or browse using the Resources tab above.

PART SEVEN:

FROM THE FOUNDATION

OF THE HOLY ROMAN EMPIRE

TO THE END OF THE CRUSADES

(800 A.D. to about 1300 A.D.)

This epoch is by far the most important of the Middle Ages. During these five hundred years the later European states entered into existence; a method of government was formed suited to the times; intellectual and religious life produced efficient and flourishing institutions; the several states developed each in its own characteristic fashion; the crusades (1096—1291) exerted a far-reaching influence upon the political and religious conditions of the continent.

CHAPTER XXXII

THE BEGINNINGS OF THE LATER EUROPEAN STATES

DISRUPTION OF CHARLEMAGNE’S EMPIRE

446. Louis the Pious (814—840). — The great Emperor died 814 A.D. and was succeeded by his son Louis. Louis had shown himself on many occasions an able general and administrator, so that Charles closed his eyes full of hope for the future of his vast empire. For years everything went on much the same way as under Charles, though the time of great conquests was past. Emperor Louis was conscientious and pious. He did much for the conversion of the Slavs in the east and the Scandinavians in the north. But he lacked the firmness and energy of his father. Following the advice of ambitious and selfish persons, he entered upon the plan of dividing the Empire among his sons, trying no less than seven schemes, each followed by greater dissatisfaction. Wars resulted between the sons and the father and among the sons themselves. The Emperor was the victim of their jealousy. Once they forced him to abdicate and remain for some time in a monastery. He was allowed to resume his dignity, but death alone preserved him from a new humiliation. The Empire suffered greatly from these domestic wars as well as from the inroads of the Northmen (§ 450 ff.), which did not meet with vigorous resistance and which increased in number and violence under the following reigns.

446. Divisions of the Empire after Louis the Pious. — After Louis the Pious’s death, his sons concluded the Treaty of Verdun, 843 A.D., which may be said to have begun the map of modern Europe. Lothair, the eldest, held the title of Emperor and was given northern Italy with a strip of land from Italy to the North Sea. His two brothers, Louis the German and Charles the Bald, received the parts east and west of Lothair’s realm.

The eastern kingdom, purely German, developed later into Germany. In the western kingdom the sparse Teutonic elements were being absorbed rapidly into the old Gallic (Celtic) population, and its territory corresponded fairly well to the extent of the French language then rising into use (§ 401). How this part came to be called France will be seen in its place.

Lothair’s unwieldy middle kingdom naturally proved the weakest of the three states. It lacked unity. Its population belonged to different races and spoke several very different languages. It was besides cut into several parts by the Alps and the heights north of the Rhone valley. Lothair himself divided it among his three sons. Louis II followed him as Emperor and ruler of (northern) Italy; Burgundy became another kingdom; and the rest, north of Burgundy, went to Lothair II. This latter part retained Lothair’s name, being called Lotharingia or Lorraine. It then embraced much of the eastern part of the present France, nearly all Belgium, all Holland, and much German territory west of the Rhine. This Lorraine became the bone of contention between its two neighbors, neither of whom had any more claim to it than the other. Eventually it was incorporated in the eastern kingdom, in whose undisputed possession it remained for centuries.

447. Final Division. — Once more all the parts of Charlemagne’s Empire were united under Charles the Fat. Three years later, in 887, they fell apart for the last time. There then existed five kingdoms in its place:

(1) that of the East Franks (Germany) including Lorraine;

(2) that of the West Franks;

(3) that of northern Italy (commonly referred to simply as Italy or Lombardy);

(4) and (5) the kingdoms of Upper and Lower Burgundy (soon to be united). These five kingdoms, together with the Papal States, were the states of the continent of Christian Europe of that time, that is, toward the beginning of the tenth century.

448. Weakness of the Carolingian Kings. — The ninth century saw a number of scandalous family wars between the kings. Brothers and cousins fought against one another. The ferocious Northmen devastated not only the coasts but even the cities far inland, and this sometimes with the connivance of the rulers.

The royal power suffered greatly by these dissensions. Two points in particular should be kept in mind to understand the conditions of the subsequent times.

(1) In nearly all the provinces of the Empire there again rose men who arrogated to themselves the power of dukes, a power which Charlemagne had taken so much pains to abolish (§ 439), and this power even became hereditary.

(2) The royal dignity again became elective in the fullest sense of the word, and of course the dukes had a decisive influence in the election.

In Germany the line of Charlemagne died out with Louis the Child, in 911 A.D.; in the western kingdom with Louis the Sluggard, in 987.

One of the several Carolingian kings was always Emperor, crowned by the Pope. Naturally the emperors often lacked the political and military power necessary to achieve much for the protection of the Church. One of the stronger ones, Arnulph, called the Carinthian, King of Germany, inflicted a defeat upon the Northmen, in 891, which kept them from harassing Germany any further. He could, however, do little for the safety of the Pope. The last of these Emperors, a relative of the Carolingians, was Berengar, King of (northern) Italy. After his death, in 924, the dignity remained in abeyance until 962.

449. The Papacy. — Several good and even great pontiffs ruled during the first half of the ninth century. Later the weakness of the emperors caused the Roman factions to raise their head and to intrude unworthy men into the papal chair. Yet even these, once they were in possession of that exalted office, commonly worked with more or less zeal for the welfare of the Church. (The time of about 900 A.D. is the darkest period of the Papacy. More than one pope died a violent death.)

The Carolingian emperors did not meddle in the government of the Papal States. It happened, however, in later times, that individual cities — the cities possessed a great deal of home rule — overstepped their legitimate rights, or that subject princes defied the authority of the popes. Later emperors, too, sometimes usurped the government of those states and appointed their own men governors. The popes never allowed their claims to lapse. Somehow all these districts returned to their allegiance, though sometimes force had to be used to reduce them to due subjection. (It is not correct if historical maps mark the Papal States simply as part of the Carolingian Empire.)

THE NORTHMEN

We must now devote some attention to other nations which were destined to influence the future of Europe and were themselves to come under the beneficial sway of Christian civilization. They rise into prominence in the times of Charlemagne’s successors.

450. Character, Home, First Expeditions. — The Northmen or Norse were another branch of the Teutons, who lived in what is now Denmark, Sweden, and Norway. The people of the British Isles called all of them Danes. So far they had taken no part in the Teutonic invasions. Their manners more or less resembled those of the other Germanic tribes before these tribes had settled on Roman ground. But they possessed less political unity. They were a ferocious and hardy race. One Northman would consider it disgraceful to run from three foemen. They clung tenaciously to the old Germanic gods (§ 389).

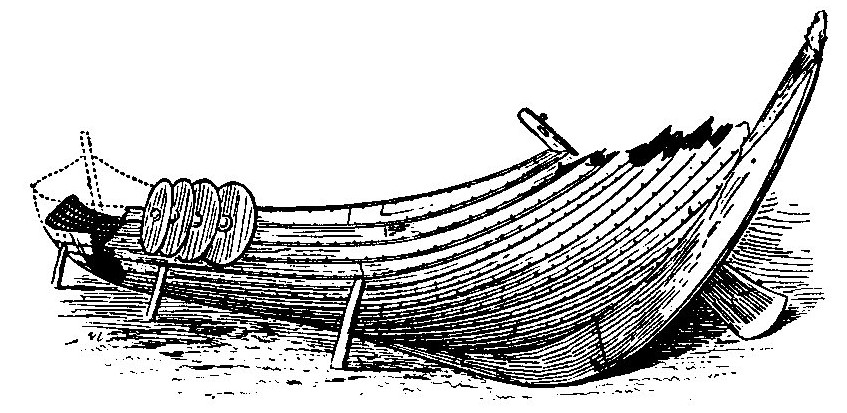

Found buried in sand at Gokstad, Norway. It is of oak, unpainted; length over all, 79 feet 4 inches.

Toward the close of the eighth century they took to the sea — “set out upon the pathway of the swans” — and started a dreadful career of piracy and depredation. For more than a hundred years they ravaged every shore of Europe including Italy. The fleets of these vikings (creek- men, sons of the fjords) sometimes counted hundreds of craft, sometimes only two or three.

The Norse ships were long, open boats, seventy-five feet by twelve or fifteen, carrying a single square sail, but driven for the most part by thirty or forty long oars. A boat bore perhaps eighty warriors; and each man was perfectly clad in ring mail and steel helmet, and armed with lance, knife, bow, and the terrible Danish ax. Daring, indeed, were the long voyages of the Northmen in these frail craft. They laughed at the fierce storms of the northern seas. “The blast,” they sang, “aids our oars; the hurricane is our servant and drives us whither we wish to go.”

Charlemagne maintained fleets to prevent pirate attacks; but in the quarrels of his weak successors the Norsemen found their opportunity. They drove their light vessels far up a river, into the heart of the land, and then, seizing horses, harried at will. They not only plundered the open country, but sacked cities like Hamburg, Rouen, Paris, Nantes, Bordeaux, Tours, and Cologne, and stabled their horses in the cathedral of Aachen, about the tomb of Charlemagne.

Ireland was invaded for the first time in 795. For some decades the raids were confined to the small islands, many of which were inhabited by colonies of monks. But the “Danes” soon found their way inland. A defeat at Killarney merely deterred them for some years. As on the continent it was political disunion of the inhabitants that made these frightful devastations possible. The invasion of Britain will be treated in §§ 464-466.

Everywhere the chief object of their attacks was the churches and monasteries. There they found the most desirable booty — richly woven and splendidly decorated cloth, vessels of gold and silver, and sometimes treasures deposited for safe keeping. But these scornful worshipers of Thor and Wotan were also prompted by a blind hatred against “the white Christ.” Priests and monks and nuns suffered the most cruel persecution. The marauders seem to have been instigated by the thousands of heathen Saxons who had sought refuge in the North from the sword of Charlemagne (§ 433).

451. Norse Settlements. — (1) So far the Northmen had been mere plunderers. But things changed in their Scandinavian homes. Three prominent chieftains consolidated the countless petty dominions into the kingdoms of Denmark, Sweden, and Norway and established some semblance of law and order. Discontented spirits, who found submission too irksome, now began to leave in search of permanent abodes.

Christianization of Scandinavia had been begun by St. Ansgar, Bishop of Hamburg, with the support of the Emperor Louis the Pious, but the national conversion belongs to a later date. The Northmen who settled in other lands, too, were converted, so that about 1000 A.D. this whole race, including in particular the kingdoms of Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, had entered the family of Christian nations and was participating in the blessings of genuine civilization.

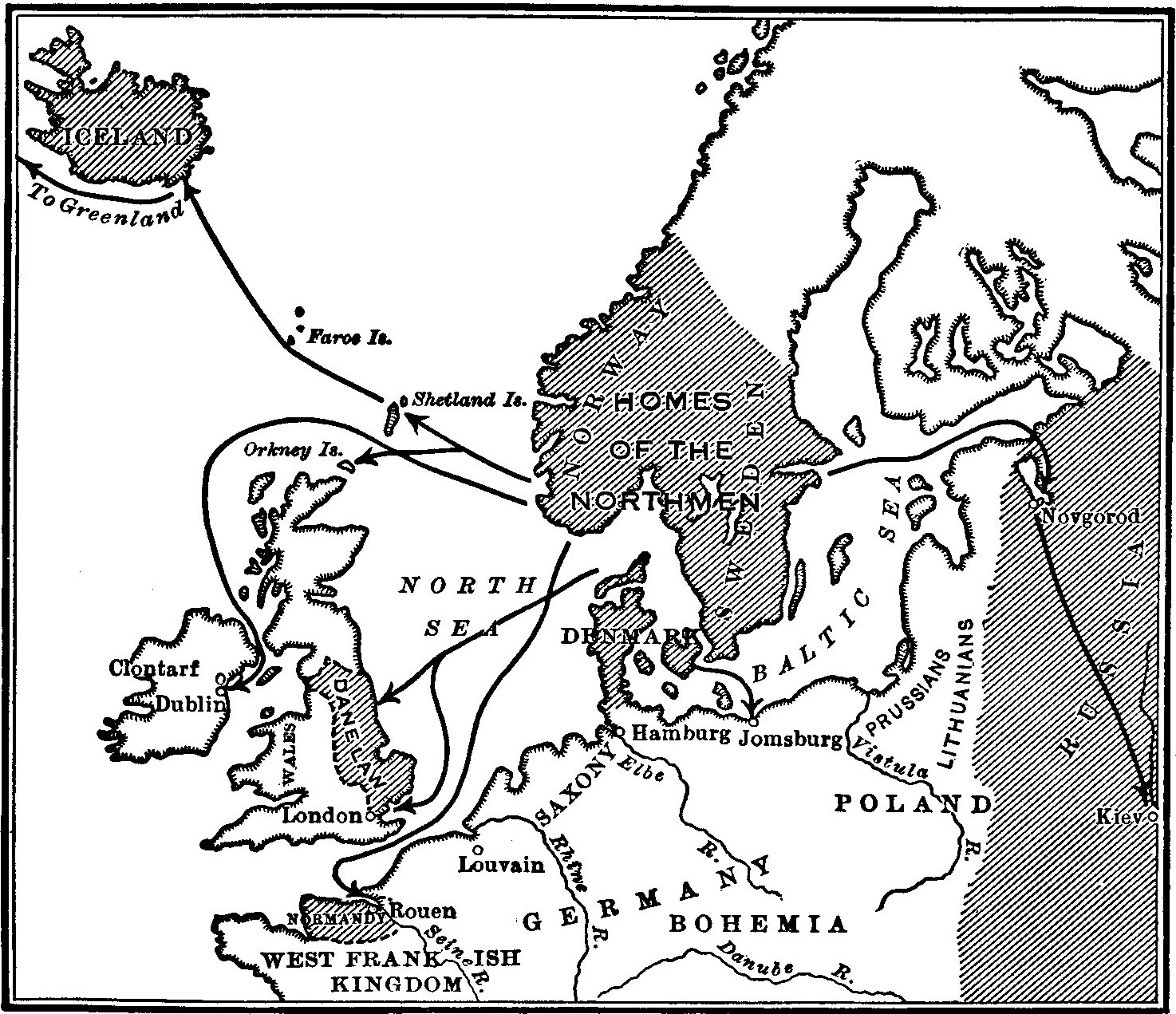

(2) The Norse established themselves on the Orkney, Shetland, and Faroe Islands. On Iceland they founded a republic and, under the leadership of the Church, maintained a vigorous religious and literary life until the time of the Reformation. Another “Danish” republic arose on the western shore of Greenland. Thence the Norse seem to have made regular trips to the coast of America. In Ireland, too, they now meant to stay. Dublin became their principal seat. The opposition of the valiant but disunited Irish chiefs was unable to check them. It was only in 1014 that the Irish, fairly well united under the brave Brian Boru, defeated them completely in the battle of Clontarf. The inroads stopped. The numerous “Danes” who remained in the island lived on peacefully among the natives. But the famous Irish schools (§ 405) never recovered their ancient renown.

The Northmen of Sweden had always turned toward the other shores of the Baltic. Here one of their chiefs, Rurik, became ruler of a Slav principality, later on called Russia, which accepted Christianity from Constantinople. The house of Romanov replaced Rurik’s line in 1598, and ruled until our own days.

(3) But their most important settlement was Normandy. In 911 Charles the Simple, King of West-Frankland, stopped the Norse raids in his country by planting some of the invaders on the northern coast to defend it against their kinsmen. The chieftain of these settlers was Rolf the Walker, so called because it was said he was too gigantic for any horse to bear. He and his followers accepted Christianity, and agreed to acknowledge Charles as overlord for their district, which henceforward was known under the title of Dukedom of Normandy. Rolf’s Northmen took their abodes among the inhabitants of the little country, and like the Teutons in other lands became the ruling class. The admixture of Norse blood gave to the population a robust vigor and a remarkable spirit of enterprise. The little dukedom of the “Normans” was destined to have an influence upon the history of Europe quite out of proportion to its size.

THE NATIONS OF THE EAST

The conversion and civilization of the territories of the Slavs and Hungarians, which in extent almost equal the rest of Europe, was a very important chapter in the development of the continent. This noble conquest lasted several centuries. It cannot be ascribed to one individual grand personage. Popes and emperors, bishops and devoted monks, chieftains and royal princesses, claim a share in the gigantic achievement. Most prominent, however, are the central figures of the “Apostles of the Slavs,” Sts. Cyrillus and Methodius.

THE SLAVS

452. Homes and Character of the Slavs. — By this time the Slavs had occupied the countries evacuated by the Teutons in the Migration of Nations. They were the eastern neighbors of the Frankish kingdom. After the breaking up of the latter it was the German realm which had to deal with them. A wedge of Germans and Avars — later on replaced by the Hungarians — divided them into a large northern and a smaller southern branch.

The southern Slavs, called Jugo-Slavs, were Christianized early, partly from the West, partly from Constantinople. At the time of Charlemagne the northern tribes were still given to the old national paganism. They adored a god of thunder, Perun (Peruna); a god of hospitality and war, Radegast; and on an island in the Baltic there stood a four-headed statue of the god Swantewit. Human sacrifices were of ordinary occurrence. The priests ruled over the people with almost absolute authority and always acted as judges. Slavic poetry shows a propensity to the melancholic. The people were brave, and proud of their national liberty. Those living farthest in the East, chiefly the Russians, received Christianity from Constantinople. Along the eastern boundary of the Frankish realm there were, next to the Danube, the Moravians, northwest of them the Bohemians, and farther north a number of various tribes reaching as far as the Baltic. Moravians and Bohemians are comprised under the name of Czechs. The tribes east of these three sections are spoken of as the Poles and their country as Poland.

453. The Moravians. — By his expedition against the Avars (§ 434) Charlemagne had secured the existence of Moravia. In 830 A.D. the first Moravians were baptized at the court of Louis the Pious. But the work of the German and Italian missionaries was not very fruitful, because they did not master the language sufficiently. Moravia’s greatest ruler was Swatopluk (870-894), who made even Bohemia a part of his realm. At first in alliance with King Arnulph (§ 448), then in opposition to him, he was prompted by both religious and political motives to ask the Emperor of Constantinople for missionaries who would know the Slavic tongue. Sts. Cyrillus and Methodius were sent, — two highly educated brothers, who had already learned the language before they knew of this mission. These saints are considered the apostles of the Slavs. Though they never went to Bohemia or Poland, their influence greatly aided in the conversion of these two countries. They translated the Bible into Slavic. After St. Cyrillus is named the Slavic alphabet, which is still in use in Russia. With the permission of the Pope they even said Mass in Slavic, following, however, the Roman usages and ceremonies. (In 1893 Pope Leo XIII again sanctioned this privilege for a number of Slavic dioceses.)

The political friction between Swatopluk and Arnulph was unfortunate for both Moravia and Germany. Arnulph invited the heathen Magyars (Hungarians) to an attack on Moravia. The destruction of Swatopluk’s power left Germany open to the frightful inroads of the Magyars, who harassed Germany until 955 A.D. Later on Moravia always appears as a dependency of the kingdom of Bohemia.

454. The Bohemians. — In 845 King Louis the German persuaded fourteen Bohemian chieftains who visited him to receive baptism. Later, through the influence of St. Methodius, the Duke of Bohemia himself became a Christian. His wife, Ludmilla, was the soul of the movement in favor of the new religion. But the complete victory was not so easily won. Ludmilla’s grandson, St. Wenceslaus, was murdered by his brother. He is one of the principal patrons of Bohemia. A fierce persecution followed his death. The arms of Emperor Otto the Great, however, secured the final and permanent ascendency of the true religion. Politically the country became, together with Moravia, a vassal state of Germany. It always held a highly privileged position. Its ruler was given the title of King, and in later times he was one of the seven “electors” who had the right and duty of choosing the King of Germany. German immigration was eagerly invited because it strengthened both Christianity and civilization, and served to people desert districts, notably along the boundaries. Of all the rich Slav countries Bohemia is the richest in natural treasures.

455. The northwestern Slavs, i.e., those living east of the Elbe between Bohemia and the Baltic, were the most restless neighbors of the Franks. As soon as Saxony was made part of the Empire, war against these tribes became a necessity. Victories over them were always followed by attempts at conversion. At one time the whole country seemed to be Christian, only to relapse again, for a long period, into paganism. German settlements were the only effective means to secure safety from these foes. Hence, when the lands were really Christian, they had become practically German. The old inhabitants disappeared among the new. Cistercian and Premonstratensian monasteries were the chief Christianizing and civilizing factors in these countries.

456. Poland. — Missionaries from Moravia, sent by St. Methodius, penetrated into the land and brought about a number of conversions. But there was no national Christianization before the time of Duke Miescislaw. This prince, in 965, married the Bohemian princess Dombrowka, who made it a condition of her consent that the duke and his people adopt her own religion. The duke became sincerely Christian and forbade the practice of paganism. But the real founder and organizer of Poland as a Christian state was Boleslaus I Chrobry (the Glorious). During a reign of more than thirty years (992-1025) he strictly enforced Christian laws. In union with Emperor Otto III he effected the establishment of seven bishoprics, followed by the foundation of monasteries. Politically, too, his reign was a great success, though not without some reverses. He annexed several neighboring countries to Poland and was the first to assume the title of King. Since 962 Poland owed allegiance to Germany. Emperor St. Henry II (§ 556) forced Boleslaus to give up Bohemia, which was restored to its hereditary duke, and to acknowledge himself in some vague terms the vassal of Germany. This dependence, never very real, disappeared in the course of the next century. Not all of Boleslaus’ successors inherited his ability and firmness. There came a time when Poland broke up into a number of independent dukedoms, until other strong hands succeeded in uniting them again.

THE HUNGARIANS

457. The Magyars and Their Conversion. — The terrible defeat inflicted by Charlemagne upon the Avars left the country on both sides of the middle Danube practically without inhabitants. The Magyars or Hungarians, who had so far been roaming north of the Black Sea and whom King Arnulph had called to his assistance against Swatopluk (§ 453), now occupied the depopulated districts. From here they carried on, for sixty years, their devastating raids into western Europe. Contemporary chroniclers compare them with the Huns. They were small, active nomads, moving swiftly on scraggy ponies. The chief sufferer was Germany. They extended their raids as far as the Rhine, repeatedly entered Italy, and advancing through both Italy and Germany even harassed France. The German kings Henry I and Otto the Great dealt them terrific blows (§§ 549, 551), which definitely put a stop to their devastating excursions. Soon their Christianization began. Duke Geysa was married to Sarolta, the daughter of a chieftain who had become Christian in Constantinople. Geysa now, exteriorly at least, accepted Christianity and promoted its preaching among his people. His son, St. Stephen, who married the sister of Emperor Henry II the Saint, was for the Hungarians what Boleslaus Chrobry had been for Poland. Under him the domestic strifes of the numerous chieftains came to an end. The Pope gave him the title of “Apostolic King,” which the kings of Hungary have borne until our own days. Bishoprics and monasteries were established. A later reaction of the strong pagan party, frightful though it was, proved a failure.

THE ISLAND OF BRITAIN FROM ROMAN TIMES TO ALFRED THE GREAT

THE ANGLO-SAXONS AND THEIR CONVERSION

458. The island of Great Britain was originally inhabited by several races of Celts (§ 192). In the north, where now the kingdom of Scotland is, lived the Picts; in the south, the Britons, after whom the Romans named the island “Britannia.” The southern part became a Roman province under Emperor Claudius (§ 318). Though it was probably never thoroughly Romanized, it had its network of Roman roads, the most famous of which was Watling Street (see map on page 350). Roman villas rose in the open country, Roman palaces, temples, amphitheaters, in the cities. We do not know at what time Christianity was introduced. But it is sure that many Christians died in the persecution of Diocletian (§ 359). St. Alban is venerated as the first British martyr.

459. The Invaders and Their Work. — As long as the Roman Empire stood firm, the Britons were defended against the inroads of the Picts from the north. But when the city of Rome was threatened by the Visigoths (§ 394), the Roman legions left the island, and the Britons were told to shift for themselves. At the same time the Jutes, Angles, and Saxons, who had been visiting the shores of Britain as pirates, now appeared in greater numbers. The Britons invited these sea rovers to assist them against the Picts, and promised them lands for settlement. Hengist and Horsa, chiefs of the Jutes, are said to have been thus admitted in 449. Soon from friends they became enemies. Other crowds arrived from beyond the North Sea. They settled first along the eastern and part of the southern coast and slowly penetrated inland. They established little principalities, which eventually consolidated into seven kingdoms, the so-called heptarchy: Kent, the kingdom of the Jutes; Sussex, Essex, and Wessex (South Saxons, East Saxons, West Saxons), realms of the Saxons; East Anglia, Mercia, Northumbria, of the Angles.

460. This conquest lasted a century and a half, from 449 to about 600, and even then it did not cease completely. At home these nations were not grouped in large political units, and hence only small bands would set out at a time without any common plan of action. Britain, too, still had extensive forests and marshes, which offered protection to the natives and enabled them to make repeated stands. The Britons, moreover, do not seem to have laid aside military habits so completely as had the Gauls and the inhabitants of other Roman provinces on the continent.

The work of the invaders was very thorough. They brought with them their Teutonic paganism (§ 389) and an unmitigated barbarism. Their progress meant destruction with fire and sword. The Britons who escaped death at their hands crowded into the peninsulas of Wales and Cornwall, and into the districts of the northwest; or they fled across the Channel into what is now called after them Brittany (Little Britain). How many were allowed to remain as slaves or serfs, and how much was left of the population of the ruined cities, will probably never be ascertained. The newcomers were so numerous, at any rate, that their rude Teutonic dialects became the language of the parts occupied by them, with only a few words taken over from the British idiom. It is customary to refer to the new inhabitants and their language as Anglo-Saxon.

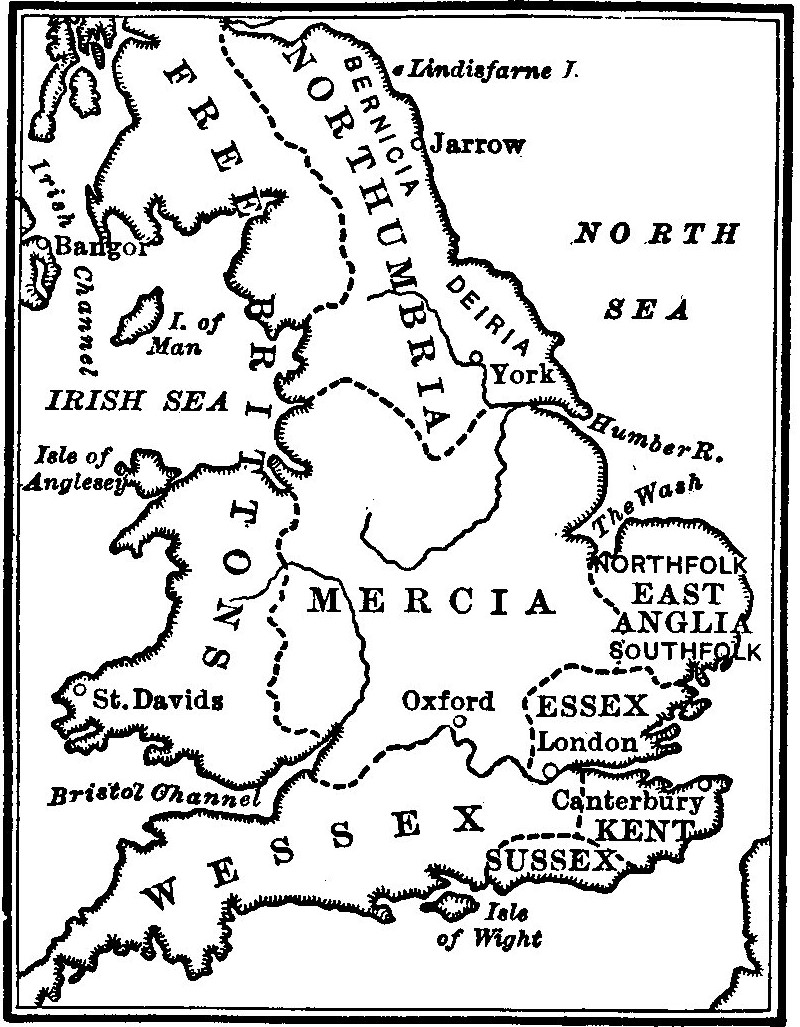

The worst effect of the invasions was the complete destruction of Christianity. Woden and Thor were worshiped in the Britain of the Anglo-Saxon. The country needed a new conversion to the religion of Jesus Christ.

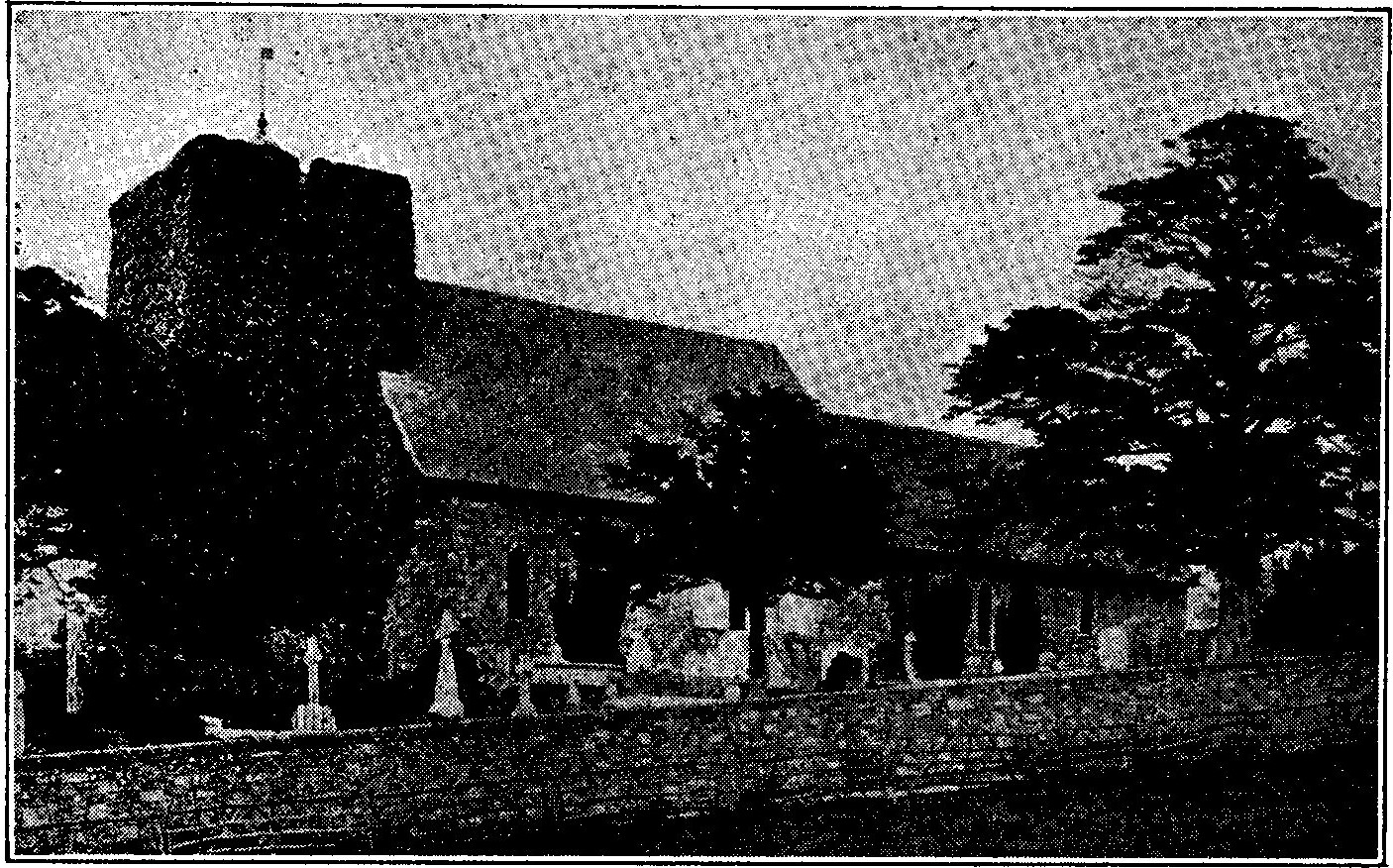

Parts of this building are very old and may have belonged to a church of the Roman period. At all events, on this site was the first Christian church in Britain used by St. Augustine and his fellow missionaries. A tomb, said to be Queen Bertha’s, is shown in the church.

461. Conversion of the Anglo-Saxons. — In 597 A.D. Pope Gregory the Great sent the Benedictine monk St. Augustine with forty companions to England to undertake the Christianization of the new occupants. The king of Kent had married Bertha, a Frankish princess, who willingly lent her support to the missionaries. The king received baptism and allowed and encouraged the preaching of the Gospel in his kingdom. St. Augustine became the first Archbishop of Canterbury and “Primate” of all England. With the assistance of the Kentish king, St. Paulinus began his activity as apostle of Northumbria and established the see of the archbishops of York. East Anglia was also gained for the faith. But an invasion of Northumbria by the united forces of Penda, the pagan king of Mercia, and the Celtic king Cadwallon, “a Christian but worse than a pagan,” destroyed much of Paulinus’ work. The Celts of the western peninsulas had refused to cooperate with the Roman missionaries. Now those of the north came to the rescue. St. Aidan and other Irish monks arrived from Iona (§ 405). Assisted by King St. Oswald, they recovered the lost ground and perfected the conversion of the whole kingdom. The other kingdoms were won partly by the zeal and influence of Roman missionaries from the south, partly by the activity of the “Scots” from the north. St. Theodore, Papal Legate and Archbishop of Canterbury (668-690), completed the work of ecclesiastical organization. The kingdom of Sussex, as the last, was converted in 681 by St. Wilfrid.

462. Results of the Conversion. — (a) While Anglo-Saxon paganism completely lacked common organization, Christianity now formed a strong religious tie, which embraced all kingdoms.

(b) A more lively intercourse was created by the national councils, in which the bishops of the whole country met to discuss common interests.

(c) By this intercourse, and by the influence of Latin, the primitive dialects were welded together into a more unified speech.

(d) The country entered into the intellectual life of the continent by the journeys of Anglo-Saxon bishops, kings, and monks to Rome and to the monasteries of Gaul and Italy.

(e) A large number of monasteries and of monastic and episcopal schools rose in the country.

(f) Although the wars waged by the Christian states among themselves and with the Britons remained bloody enough, they were at least not attended by such wholesale destruction as before.

The first three advantages in particular helped to prepare the political union of the country.

463. Political Union. — In the course of Anglo-Saxon history several kings wielded an influence that extended beyond their own particular kingdom. They are called “bretwaldas” (broad-wielders). But each bretwalda’s power rested on his own ability and success. Nor did any one of them ever extend his sway over all the other kingdoms. In the beginning of the ninth century King Egbert of Wessex, of the family of Cedric, rose to this position of Bretwalda. He first enlarged his own kingdom by adding the Celtic Cornwall. He then brought all the Teutonic parts of the island to acknowledge his overlordship. England — for at that time this name came into use —was indeed still far from being one compact state. Still there existed about 830 A.D. at least some kind of political union. From Egbert on there has been a united England. Never were the several kingdoms to rise again as separate and independent political units. This progress of consolidation was greatly facilitated by the invasions of the Northmen.

THE DANISH INVASIONS — ALFRED THE GREAT

464. The Norsemen, called Danes in England, invaded England as they did the continent, first for plunder, then for conquest and settlement. Their sackings and devastations were of the same character (§ 450). In 850 they made their first permanent settlement. Soon district after district came under their power. By 871 the Danes were masters of all England, the last king of Wessex having fallen in battle. This marked the beginnings of one of the most glorious epochs of England’s history, the time of Alfred the Great.

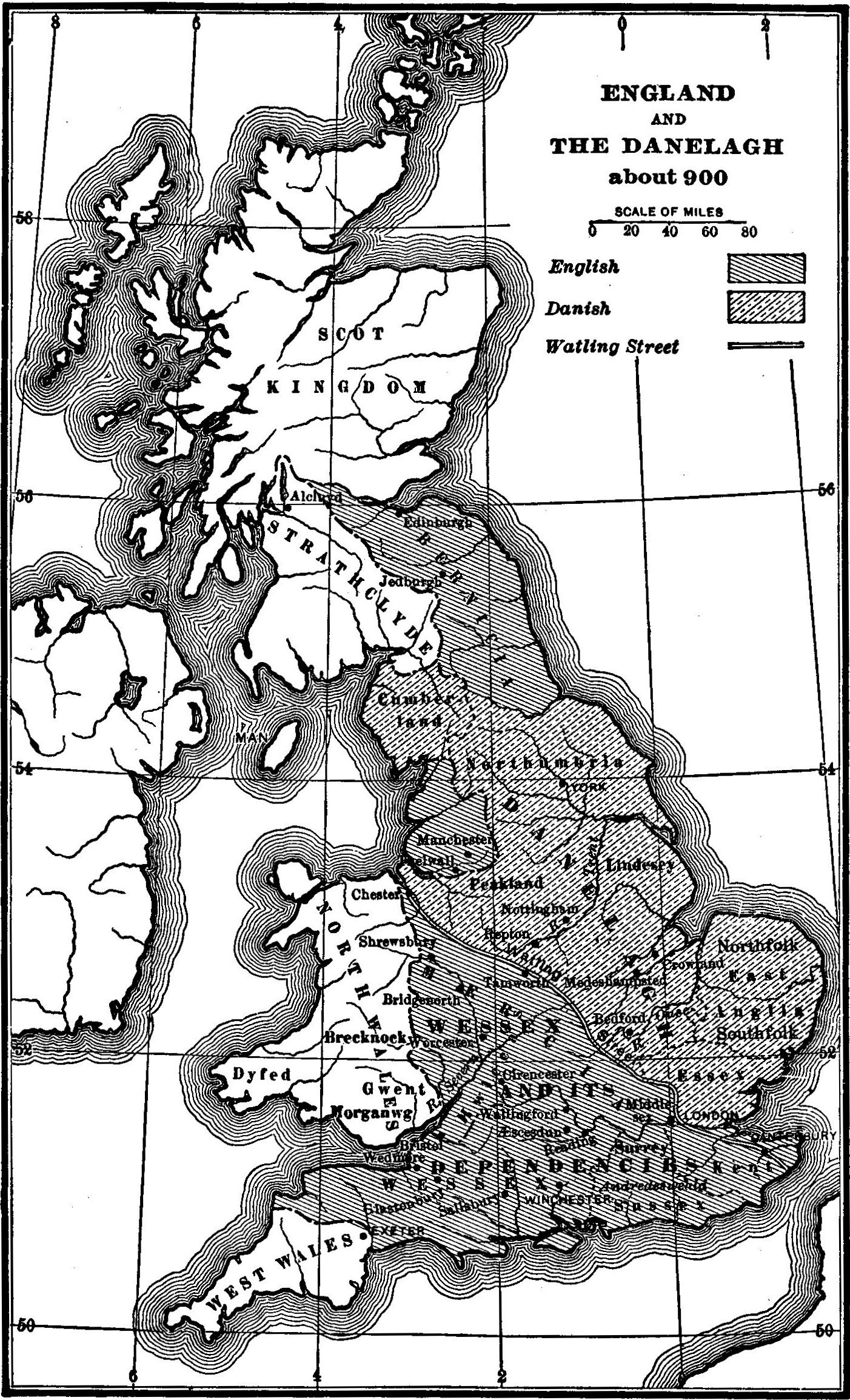

465. Alfred the Great (871—901). — He was the youngest brother of the fallen king and King Egbert’s grandson. At first he concealed himself in marshes and fens. But he soon contrived to make himself formidable to the invaders. The Danes were signally defeated. By the treaty of Wedmore, 878, Guthrum, their king, consented to rule one part of England as a vassal of Alfred. A line running from London northwest through Mercia, mostly along Watling Street, the famous Roman road, divided the territories. Guthrum himself adopted Christianity and ever remained faithful to the promises he had made to Alfred, now his godfather. However, Alfred’s overlordship over the “Danelagh” (Dane-Law) — the land of Danish rule — existed more in name than in reality. The Danelagh was practically an independent state.

Alfred’s Activity. — Alfred found the country in a terrible condition. The cities with their churches lay in ruins. The monasteries, the chief support of literary education, were destroyed. There was ignorance beyond description, not only among the laity but even among the clergy — in those days the most educated class. “When I began to reign,” wrote Alfred himself later, “I cannot remember one priest south of the Thames who could render his service-book (from the Latin in which it was written) into English.” North of the Thames, the king explains, conditions were still worse.

To strengthen England against future danger, Alfred reorganized the army and reared many a strong fort at commanding positions. Eventually to meet the enemy on his own element he created a fleet and thereby became the “Founder of the English Navy.” He rebuilt the wasted towns, restored churches and abbeys, codified the laws, reformed the government, and ardently encouraged the revival of learning, eagerly seeking out teachers at home and abroad. In the absence of proper textbooks in English for his new schools he himself laboriously translated four standard Latin works into English, with much comment of his own — so adding to his other titles the well-deserved one of the “Father of English Prose.”

Alfred’s activity was many-sided. A great historian has written of him: —

“To the scholars he gathered round him he seemed the very type of a scholar, snatching every hour he could find to read or listen to books. The singers of the court found in him a brother singer, gathering the old songs of his people to teach them to his children . . . and solacing himself, in hours of depression, with the music of the Psalms. He passed from court and study to plan buildings and instruct craftsmen in goldwork, or even to teach falconers and dog-keepers their business. . . . Each hour of the day had its appointed task. . . . Scholar and soldier, artist and man of business, poet and saint, his character kept that perfect balance which charms us in no other Englishman save Shakespeare. ‘So long as I have lived,’ said he as life was closing, ‘I have striven to live worthily’; and again, ‘I desire to leave to men who come after me a remembrance of me in good works.’ ”

466. Alfred’s successors, his son, grandson, and great-grandson, took the offensive against the Danes. Edward the Unconquered, Athelstan the Glorious, and Edmund the Doer of Deeds, contributed each his share to reconquer the Danelagh, without, however, altogether driving out the Danish inhabitants. Under Edgar the Peaceful the country rested undisturbed. He never had to unsheath his sword, though he was ever ready for war, often displayed his military strength, and every year sailed with a fleet of three hundred ships around the whole island to inspire his enemies with a wholesome fear. Even the kings of the Celtic tribes in the far west and north came to his court to pay him homage. Under the strong and just government of Alfred’s successors the old differences between the seven Anglo-Saxon realms and their separate aspirations disappeared entirely. England was one kingdom.