The following is an excerpt (pages 456-471) from Ancient and Medieval History (1944) by Francis S. Betten, S.J. Although some information may be outdated, the Catholic historical perspective it provides remains pertinent. Use the link at the bottom of post to read the previous/following pages. Use the Search box above to find specific topics or browse using the Resources tab above.

CHAPTER XL

THE CRUSADES

THE CHRISTIAN AND THE MOHAMMEDAN ORIENT

586. The Christian Orient: the Byzantine Empire. — To the description of Byzantine culture given in § 411 should be added mention of the endless number of court intrigues and palace revolutions with their revolting cruelties. After Charlemagne’s time the Empire constantly diminished in size. Palestine, Syria, Egypt, and northern Africa had been lost in the first onrush of the Mohammedans (§ 421). Slav nations were encroaching from the north upon the European provinces, until about 1000 A.D. the Bulgarian kingdom succumbed to the Emperor Basil II. Armenia and Cilicia, too, were reconquered. But soon after, all Asia Minor was torn away by the Turks and the remnant of the Byzantine possessions in Italy by the Normans (§ 562).

The Great Eastern Schism was the saddest event in the history of this Empire. The bishops of Constantinople had, with the subsequent sanction of the Pope, assumed the title of Patriarch. Though there were among them many eminent and saintly men, others openly championed heresies, or showed too great a subserviency to the emperors. The contempt with which the East now looked down upon the entire West including Rome, and the ignorance of Latin in the East and of Greek in the West, helped considerably to widen the breach between the two parts of Christianity. For several hundred years the schisms caused under these circumstances through the pride of either emperor or patriarch had been short-lived. But in 1043 the arrogant patriarch Caerularius again fell away, and this time the split remained unhealed. The schism completed the estrangement between the East and the West. It partly accounts for the little sympathy which was given in Constantinople to the western crusaders in their struggle against the common foe of Christianity.

Materially and intellectually the Eastern Empire, though so much reduced in size, remained the most civilized part of the world. Were we transferred into those distant times, nowhere should we find so near an approach to the methods of our own city and state administration, our police system, our own institutions of learning and of public and private charity. And notwithstanding its weakness and losses the Empire had so far fulfilled its mission of keeping the Mohammedans out of Europe and checking the advance of the semibarbarous nations which inhabited the northern coasts of the Black Sea.

587. The Mohammedan Orient. — Soon after the death of the Prophet religious dissensions rent the unity of the Mohammedan world. The Sunnites admitted, as a rule of their faith, besides the Koran (§ 420), an oral tradition which the Shiahs rejected. The latter did not recognize the caliph of Bagdad as the legitimate successor of Mohammed. They set up another caliphate under the “Fatimites” in Egypt and northern Africa with the new city of Cairo as capital. Their power often extended far into Asia.

Meanwhile the actual power of the caliphs of Bagdad had passed to the Seljuk Turks, a Turanian race from east of the Caspian Sea. Caliphs had formed a bodyguard of Turks, which soon became the real power in the state. Its “sultan,” a descendant of Seljuk, was the actual ruler, while the caliph remained a religious figurehead.

There existed, therefore, toward the end of the eleventh century, the following Mohammedan powers: in Spain the ever- diminishing caliphate of Cordova; in Egypt and northern Africa the caliphate of the Fatimites; in Asia the caliphate of Bagdad, ruled in name by the caliphs, in reality by the Seljuk Turks, and divided into several “emirates.”

THE CRUSADES

588. Origin and Nature. — The scenes of the sufferings, death, and resurrection of Our Lord had always been the most cherished goal of pilgrimages (§ 499). Undaunted by the hardships of the long journey, and their ignorance of countries and languages, thousands set out from all parts of western Europe. The conquest of Palestine by the first caliphs (§ 421) rendered these pious journeys more difficult, as the pilgrims were now obliged to pay a fee for admission to the city. Conditions became much worse when, in 969, the Fatimite caliphs of Egypt became the masters of the Holy Land. The Church of the Holy Sepulcher and countless other churches were destroyed. In 1076 the Seljuk Turks conquered Jerusalem from the Fatimites, subjected the native Christians to unheard-of vexations, and replaced the pilgrims’ tax by a system of robbery and extortion. By hundreds and thousands the pilgrims went to Palestine and returned by units and tens to spread the tale of the miseries they had witnessed. Their sad reports brought home to all Christians the shame and humiliation of seeing their most holy places in the power of the infidel.

It seems that Pope Gregory VII (§§ 578 ff.) was the first to conceive the idea of a military expedition for the purpose of ending both the degradation of the Holy Land and the sufferings of the Christians. In 1095, another Pope, Urban II, took this matter vigorously in hand. In a council held at Clermont he appealed to all the Christian nations and rulers to combine in a great undertaking, an armed pilgrimage. His eloquence thrilled the multitudes with holy enthusiasm, and spontaneously from the listening crowds rose the cry, “God wills it! God wills it!” This became the rallying cry for the sacred wars. Wandering preachers roused the population of the more distant lands. Those who pledged themselves to the expedition fastened a cross upon their breast — hence the names crusader (cross-bearer) and crusade. Thousands and hundreds of thousands took the cross. Thus began a movement of truly gigantic proportions, the like of which the world has never seen. For two hundred years army upon army of pious volunteers traveled to a far-distant land, underwent incredible hardships, and faced an almost certain death, from the noblest and most unselfish motives. They were prompted by the desire to do penance for their sins, and by other pious considerations, but the mainspring of their enthusiasm was their warm personal devotion to Jesus Christ, the Savior of mankind, the King of Kings.

True, some crusaders went merely in a spirit of military ardor, or to gain temporal possessions in the land they hoped to conquer. Even baser promptings were not absent. None the less the real cause of the crusades was religious zeal. They were real “Wars of the Cross.” The grosser motives helped to rally recruits around a banner which religious enthusiasm had set up.

The crusaders enjoyed many ecclesiastical privileges. From the moment a man had taken the cross, the Church forbade under pain of excommunication all attacks, even by law, upon his person or property, until he had returned home. She also granted him what would now be called a plenary indulgence, provided he would keep his vow or die in fulfilling it.

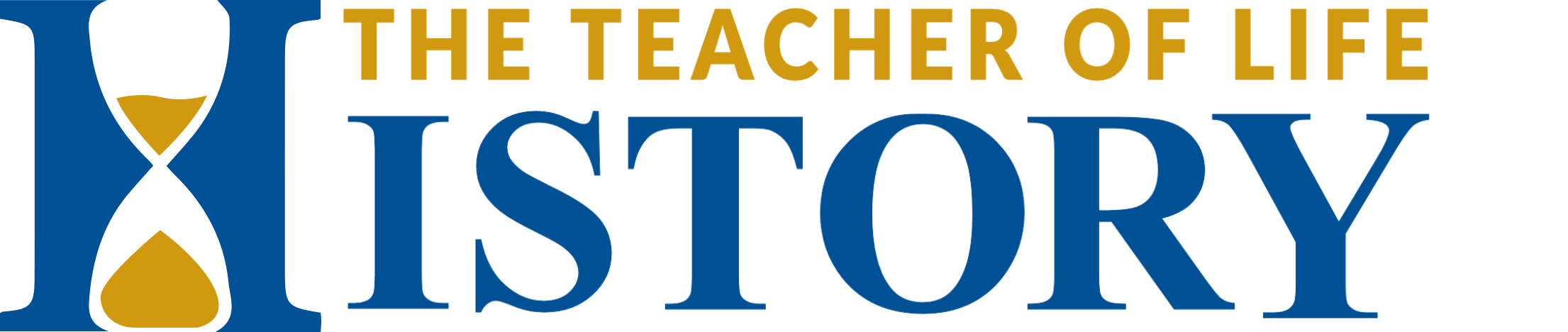

The crusades were one continuous movement. This armed migration went on uninterruptedly for two centuries, from 1096 to 1292 A.D. The seven or eight crusades commonly distinguished by historians were merely the highest waves of the incessant flood.

589. The First Crusade. — From nearly all parts of Christendom crusaders flocked together, chiefly from northern France and southern Italy. None of the Christian kings of Europe, but a number of prominent vassal princes joined this crusade. (It is evident that neither Henry IV of Germany nor William Rufus of England was apt to become enthusiastic for so unselfish a project as the crusades (§§506, 579-582). Philip I of France was not much better but shrewder than both. (Guggenberger, I, § 390.)) The most renowned of them is Godfrey of Bouillon, Duke of Lower Lorraine. A papal legate supplied in some measure the lack of centralization in the command.

From a thirteenth-century manuscript, now in the British Museum, London.

A multitude of more than three hundred thousand, the chroniclers report, set out with the princes in the spring of 1096. The Greek Emperor, who had himself been imploring the Pope for help, now that the crusaders arrived in his dominions, gave them little assistance. They overcame the Turkish army which opposed their advance in Asia Minor. During their further march their numbers were considerably reduced by want of every kind. Still they conquered Edessa, beyond the Euphrates, and the strongly fortified city of Antioch in Syria.

The following year they took Jerusalem after a desperate resistance on the part of the Mohammedans. Godfrey was the first of the princes to leap from his siege tower upon the walls of the city. Then followed scenes which will ever remain a disgrace to the crusaders. Incensed by the fierce resistance and probably fearing new dangers, they put to death the whole garrison and nearly all the Mohammedan inhabitants. Three days later, clad in white garments, they went in solemn procession to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and the other sacred places of Jerusalem.

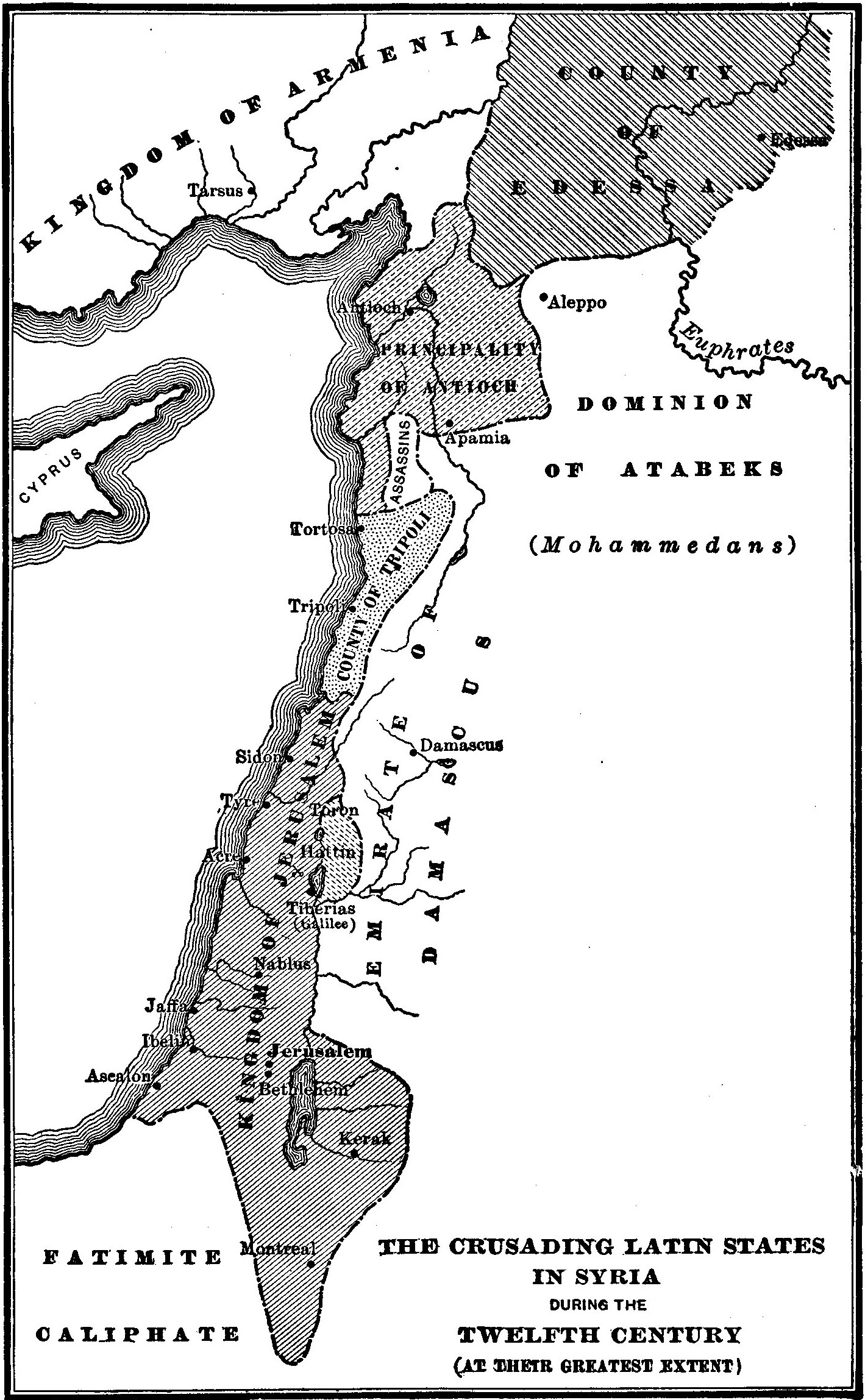

590. Results of This Crusade. — The crusaders erected the country of Palestine into a Kingdom of Jerusalem, and elected as its king their most popular and best-beloved hero, Godfrey of Bouillon. But Godfrey refused to wear a royal diadem in a place where Jesus Christ had worn a crown of thorns, and styled himself Protector of the Holy Sepulcher. His worthy brother and successor, Baldwin, admitted the royal title. Several smaller “Latin” states were formed along the coast and beyond the Euphrates as fiefs of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. (All the states founded by the crusaders are called “Latin,” because their priests used Latin in their services, not some Oriental language as did the native priests. See map on page 462.) The crusaders knew of no system of government except feudalism. So each ruler divided his lands in feudal fashion among his followers who cared to remain in Palestine. Churches, monasteries, and other Catholic memorials soon marked all the spots which are sanctified by Our Lord’s life and actions. French became the language of the Christian settlers, who, however, were confined to the larger places. The open country remained, for the most part, in the power of hostile Mohammedans, and traveling was very unsafe.

591. The Knightly Orders. — The Latin States possessed rather precarious resources. Their existence depended on the influx of new volunteers from western Europe. Nor did the rulers themselves always act in unison with one another. The never failing fertility of the Church came to the rescue. Unselfish noblemen formed themselves into new religious orders, and devoted their whole lives to the fight against the infidels. They admitted also priests to look after their own and their subordinates’ spiritual welfare both in the field and at home; and they had “brothers” to take care of domestic affairs, or, occasionally, to command detachments of infantry. The Order of the Knights Templar was founded in 1118; the Order of the Knights of St. John a few years later; and the Teutonic Order in 1197. (The present Knights of St. John, who are organized in so many Catholic parishes, are not connected with the ancient order. Much less have the Knights Templar of to-day, a prohibited society, anything to do with the Knights Templar of crusading fame.) These bands of devoted warriors, who had renounced all earthly ambition, supplied much of the fighting force that was necessary to maintain, in the absence of a numerous influx of armed pilgrims, the hold of the Christian West upon the distant Latin States.

The crusaders were almost always forced to fight against vastly superior numbers. Next to Divine Providence their victory is due to their incredible bravery and boldness. Greater daring and prowess and more display of skill and physical strength the world probably has never seen. The well-deserved renown of invincible valor contributed largely to the relative security of the Christian conquests.

592. Some letters from the crusaders give curious and interesting side lights on their motives and feelings. One of the leaders was Stephen, Count of Blois, who had married a daughter of William the Conqueror and was the father of the young prince afterward known as King Stephen of England (§ 536). In 1098, from before Antioch, Stephen sent to his “sweetest and most amiable wife” the following letter: —

“You may be sure, dearest, that my messenger leaves me before Antioch safe and unharmed, through God’s grace. … We have been advancing continuously for twenty-three weeks toward the home of our Lord Jesus [since leaving Constantinople]. You may know for certain, my beloved, that I have now twice as much of gold and silver and of many other kinds of riches as when I left you. … You must have heard that, after the capture of Nicaea, we fought a great battle with the perfidious Turks, and by God’s aid, conquered them. . . . These which I write you are only a few things, dearest, of the many which we have done. And because I am not able to tell you what is in my mind, I charge you to do right, to watch over your land carefully, to do your duty as you ought to your children and your vassals. . . .”

593. The Second Crusade (1147-1149). — In 1147 Europe was alarmed by the fall of Edessa, the farthest outpost of the Christian power. Pope Eugene III at once called upon all the Christians for a second great effort on behalf of the Holy Land. He commissioned St. Bernard (§ 501) to preach a new crusade. (When the great preacher entered the cathedral of Speyer, the Salve Regina was being chanted. Deeply moved by the devotion of the immense crowd he is said to have added the words, O clemens, O pia, O dulcis Virgo Maria (“O clement, O loving, O sweet Virgin Mary”) which have remained attached to the beautiful prayer. They were engraved on the pavement of the Speyer cathedral.) Conrad III, Roman King (§§ 553, 558), and Louis VII of France put themselves at the head of immense forces. But the grand enterprise failed, partly from bad generalship, partly from dissensions among the crusaders. Nevertheless the number of warriors who thus reached Palestine was of considerable assistance to the Latin States.

594. The Third Crusade (1189-1192). — Another Turkish power had meanwhile arisen from among the parts of the Seljuk dominions (§ 587). The chief representative of this power was the redoubtable Saladin, who tore province upon province away from the Christian defenders. In 1187 the incredible happened: he entered the Holy City as conqueror. All Christendom was staggered. The greatest three potentates of Europe, Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, King Philip II of France, and King Richard I the Lion-Hearted of England, arranged a third crusade (§§ 526, 542, 558). It was much better organized than either the first or the second. The severest loss of this crusade was the death of the great Emperor, whose enthusiasm and military experience had much to do with the initial successes. The two kings soon fell to quarreling. Philip was the first to return home. Yet the crusade was far from fruitless. Richard and Philip, combining their forces for a time, had reconquered the important coast fortress of Acre. Richard the Lion-Hearted filled the Orient with the terror of his name. Though his brilliant exploits did not lead to the recovery of Jerusalem, he secured other advantages. It is to his credit that the whole coast line was returned to the Christians and strongly fortified, and that free access was guaranteed to the Holy Sepulcher.

“On one occasion, near Emmaus, he (Richard) attacked single-handed a horde of Turks, slew twenty and chased the rest before him. With only fifty knights he scattered another large army at Jaffa. Saladin himself fled before him like a hunted hare.” Guggenberger, I, § 514.

595. The Fourth Crusade (1197-1204). — Contrary to their vow the leaders of this crusade went to the assistance of a dethroned emperor of Constantinople. New and unexpected revolutions caused the crusaders to take the city by storm, to set up a “Latin” emperor, and to parcel out sections of Greek territory to vassal princes. The Republic of Venice occupied a number of cities and islands on the Grecian coast. Pope Innocent III, at first very indignant at this conduct, finally recognized the new states in the just expectation that they would be in sympathy with crusading enterprises. — The “Latin Empire” labored under difficulties similar to those of the Latin States in Asia. In 1261 a Greek potentate reconquered Constantinople and restored Greek rule. Some of the minor states, however, survived to a later date, and the Venetians retained their possessions for centuries.

596. The Other Crusades. — Saladin had obtained possession of Egypt, where he displaced the Fatimite caliphs (§ 587). His realm included the lands from beyond the Euphrates as far as deep into Africa. After his death it broke into several fragments, ruled from Damascus, Cairo, and other capitals. The title of Caliph was still held, at Bagdad, by the powerless successors of once mighty rulers. It was at this juncture that large crusading armies attempted to approach the reconquest of Palestine by securing Egypt. They conquered Damietta, but the fact that Emperor Frederick II, contrary to his solemn promises, failed to come to their aid caused them to lose a good opportunity to regain Jerusalem (§ 566). On account of the unquestionable advantages scored ten years later by this emperor some writers count his pleasure trip to the Holy Land as a separate crusade. In 1244 the last remnants of his gains were lost.

St. Louis IX of France (§546) undertook two more crusades. In the years 1248-1254 he fought bravely, first in Egypt and then in Syria, but with little result. In 1270, when an old man, he set out again, this time for Tunis, where, after some successes, he died of fever. “Jerusalem, Jerusalem” and “Into Thy hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit,” were his last words. In St. Louis died one of the grandest characters of his times — one in whom were embodied most perfectly all the qualities of the Christian knight, king, and crusader.

This was the last great effort made to obtain possession of the Holy Land. Although the popes did not give up the idea of a reconquest, the crusading spirit had greatly cooled down in Europe. People thought, too, that in some cases the name of crusade had been used for enterprises the purpose of which was less spiritual than secular.

In 1291 Acre, the last stronghold of the Latins in Palestine, had to be abandoned. The only remnant of all the Latin possessions was the Kingdom of Cyprus, ruled by an old crusading family, which for three hundred years more withstood the assaults of the Crescent.

597. Further History of the Knightly Orders. — The Knights of St. John soon conquered, and held for two hundred years, the island of Rhodes, whence they were called the Rhodesian Knights. They were dislodged, after a heroic defense, in 1522, by the Turks. In 1526 Emperor Charles V gave them the island of Malta, and since that time they have been known as the Knights of Malta. The loss of this island in 1798 to the French induced the insignificant remnant of the order to take exclusively to works of charity, i.e., activity in hospitals in peace and war.

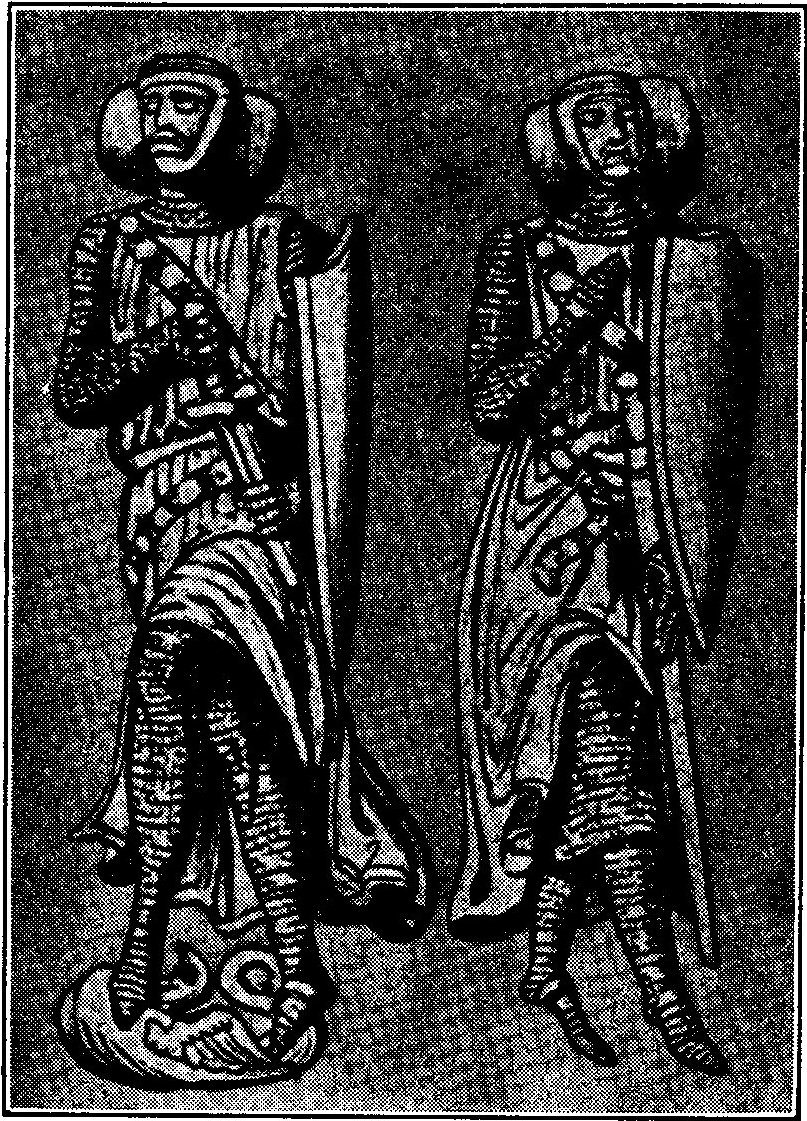

From funeral slabs in the Temple Church, London. The crossing of the legs in funeral sculpture indicated a crusader.

The Knights Templar suffered a tragic end. Their vast possessions roused the jealousy and avarice of King Philip IV, the Fair, of France. This unworthy grandson of St. Louis spared no device of intrigue and violence to bring about a condemnation of the order for heresy and immorality. Pope in Clement V, without condemning the order, decreed, in 1311, its dissolution. The accusations against the order as such, though unfounded, had undermined its good name. An organization thus slandered was not likely to be joined by young men of respectable families (§ 666).

Toward the close of the crusades in the Orient the Teutonic Order finished a crusading enterprise against a pagan nation almost in the heart of Europe. Northwest of the lower Vistula lived the fierce Prussians, a race akin to the Lithuanians farther east. They were given to a low kind of idolatry. Like the Saxons of old (§ 433) they admitted no missionaries and harassed the neighboring countries incessantly. St. Adalbert, the “Apostle of the Prussians,” and others paid with their lives for attempting to preach the Gospel to them. To end the devastations wrought by these barbarians, Duke Conrad of Masovia invited the Teutonic Order to undertake the conquest and conversion of the Prussians. (Masovia was a part of Poland. Poland had no strong rulers at that time (§ 456).) The conquest, carried on with varying success, required fifty-five years, 1228-1283. For more than a hundred years Prussia, ruled by the knights, was considered the best-governed country of Europe. It was a fief at once of the Empire and the popes. It lasted until the time of the Reformation. (See map after page 480.)

RESULTS OF THE CRUSADES

598. Failure. — The purpose for which so many thousands sacrificed all that was dearest to them, the purpose for which the popes and countless unselfish persons had been laboring incessantly was obtained only in a very imperfect way. For a brief space only were the holiest places in Christendom in the power of Christians. “This failure was the greatest misfortune that could have befallen Europe. The Turks could not have conquered, as they did conquer later on, large parts of Europe, had Europe remained mistress of Egypt and Syria. This possession would have forestalled all destruction of civilization, and we should now have more nations of our own kind in Europe” (Niebuhr). Nevertheless the heavy expenses in blood and treasure had not been made entirely in vain.

599. Military Results. — By keeping the Mohammedan powers busy in Asia the crusaders saved the life of the Eastern Empire for two hundred years more. Europe had two more centuries to develop its own civil and political institutions, before the enemy battered at its very gates. It is a significant fact that not ten years after the fall of Acre (§ 596) a Turkish chieftain, Osman (Othman), made himself master of some provinces in Asia Minor which the Greeks had reconquered after the first crusade. In Brussa, not a hundred miles from Constantinople, he established in 1299 the center of a new Turkish power, that of the Osmanic or Ottoman Turks, which became the terror and scourge of all civilized Europe.

600. Results for the Church. — A great idea, to free the Holy Sepulcher, had taken hold of Christian Europe. To realize this idea heroic efforts were made by individuals and communities, by the millions that went on the crusades, and by other millions — parents, wives, children, and friends — who sympathized with the crusaders, and though remaining at home had fully caught the crusading spirit. (James J. Walsh (The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries, page 229) thinks that much of the chronicling of crusaders’ experiences was done for the sake of the women. (See § 592.)) The source of this spirit was an intense and enthusiastic and personal love for Jesus Christ. No wonder that Christian life in general became much more brisk and active. No period can boast of so many saints in palace, hut, and convent. The foundation of the mendicant orders (§§ 583 ff.) was a fruit of this new spirit. Shortly before them another order, a very “timely” one, had been established, the “ Order of the Blessed Trinity for the Redemption of Captives,” — a counterpart of the military orders. Many thousand prisoners owe to this order their liberation from horrible servitude. The three military orders and their flourishing condition at a time when membership meant a life of hardship and sacrifice reveal an astonishing amount of lively faith among the higher classes.

The Migration of Nations had inaugurated a great missionary activity. The period of the crusades saw a new revival of apostolic zeal. It was now that final and successful efforts were made for the conversion of the Slavs on the eastern bank of the Elbe (§§ 455, 551). (An amusing incident is told of the conversion of the Pomeranians. A poor monk arrived among them as apostle. They refused to listen to him, because they said the Lord of heaven and earth could not have chosen such a beggar for His ambassador. Thereupon St. Otto, the Bishop of Bamberg, went to them, and added to the virtue of an apostle the pomp of a prince. He effected their conversion.) The Christianization of Prussia (§ 597) was the last step in this progress of the religion of Christ along the coasts of the Baltic. Finland’s conversion originated from Sweden at the same period. Lithuania alone in spite of serious efforts remained pagan for a hundred years more. Numerous were the attempts at Christianizing the Mohammedans of northern Africa. Missionaries went even to the Mongols and established a bishopric in Peking, then the capital of the vast Mongolian empire (§ 567). The popes directed, encouraged, and supported all these enterprises.

601. Intellectual Results. — The crusades brought new energies into play, and opened up new worlds of thought. The intellectual horizon widened. Men gained acquaintance with new lands, new peoples, new manners. They became desirous of discovering unknown countries. Crusading thoughts in fact had much to do with the enterprise of Columbus.

The crusaders brought back at once some new gains in science, art, and geographical and medical knowledge; and their romantic adventures furnished heroic subjects for the pen of poet and story-teller — so that literary activity was stimulated, and many histories of the crusades were written. There was a new stir in the intellectual atmosphere, and the way was prepared for a wonderful intellectual uprising. During these two centuries the universities began to rise and the great teachers to gather eager crowds of students about them (§§ 617 ff.). This, too, was the time of the grand development of architecture (§§ 625 ff.).

602. Commercial Results. — As long as the Latin States in Syria lasted, they were dependent upon Europe for weapons, horses, and even supplies of food. These things had to be transported by sea; and, during the last crusades, the crusaders themselves usually journeyed by ship. This stimulated shipbuilding, and led to an increased production of many commodities for these new markets.

Europeans, too, learned to use sugar cane, spices, dates, buckwheat, sesame, saffron, apricots, watermelons, oils, perfumes, various drugs and dyes, and, among new objects of manufacture, cottons, silks, rugs, calicoes, muslins, damasks, satins, velvets, delicate glassware, the crossbow, the windmill. Many of these things became almost necessaries of life, and, in consequence, commerce with distant parts of Asia grew enormously. For a time, Venice and Genoa, assisted by their favorable positions, monopolized much of the new carrying trade; but all the ports of Western Europe were more or less benefited. This commercial activity called for quicker methods of reckoning, and at this time Europe adopted the Arabic numerals (§ 424).

Money replaced barter. All these commercial transactions called for money. The system of barter and of exchange of services by which Europe had largely lived for some centuries was outgrown. In consequence the coinage of money grew rapidly.

603. Political Results. — After money had become common, the relations between tenant and landlord, and lord and vassal, no longer needed to rest upon exchange of services for land. Thus the economic basis of feudalism (§ 468) was weakened or destroyed. The presence of money, too, enabled the kings to collect national revenues, and so to maintain standing armies of well-drilled mercenaries, more efficient than the old feudal arrays. Thousands of barons and knights never returned from the Orient, and their fiefs escheated to their lords, frequently to the crown. Moreover, to procure the money wherewith to equip their followers for the crusades the great barons mortgaged their possessions to the kings, and sometimes the smaller vassals sold them outright. And kings as well as great vassals sold charters of rights to the rising towns to obtain money. Thus the kings acquired a more direct power over their subjects outside the cities, and the cities obtained more liberties and a greater amount of home rule. The townsmen began to figure as the “third estate” beside the higher clergy and the nobles. All this, however, varied greatly in the various countries.