The following is an excerpt (pages 354-368) from Ancient and Medieval History (1944) by Francis S. Betten, S.J. Although some information may be outdated, the Catholic historical perspective it provides remains pertinent. Use the link at the bottom of post to read the previous/following pages. Use the Search box above to find specific topics or browse using the Resources tab above.

CHAPTER XXXIII

MEDIEVAL POLITICAL SYSTEM

This chapter explains how the states of the Middle Ages came to be governed; how this resulted in a difference of classes, nobility and workers; how religion, which in all essential parts was the same as the Catholic religion of to-day, was looked upon and practiced.

FEUDALISM

467. Description. — The administration and government of present-day states, republics as well as monarchies, is carried out by officials, appointed or elected, who serve for a certain term of years and receive a fixed sum of money called salary for their services. They cannot consider their office or position their own, as they do their houses or gardens. Nor can they transmit their offices and the revenues connected with them to their sons as an inheritance.

In those times there was little money wherewith to pay salaries and other government expenses. The rulers drew their revenues not from taxes but from large landed estates (see § 438). Similarly the men who in the king’s name governed the various districts and provinces of the realm did not receive salaries as our officials do, but enjoyed the revenues from certain estates. Their services, however, were not only administrative but military as well. When called upon, they were obliged to gather their fighting men and serve in the king’s army every year for a definite number of weeks. When the holder of such an office died, all his rights and duties, as if they were private property, passed on to his eldest son. The son must, as soon as possible, present himself before the king and “pay him homage,” that is, profess himself the king’s “man” (Latin, homo, hence the word homage) or vassal. The king, in a solemn ceremony, called investiture, surrendered to him the lands and rights which the deceased vassal had possessed, just as if they were now transferred for the first time. The king could not refuse this except for very special reasons. Such land and possessions were called a fief (more rarely feud). The hereditary succession was regulated by law or contract and could not easily be changed. But if there was no son or other person that could legally inherit from a vassal, the fief escheated to the one who had granted it, who might or might not transfer it to someone else.

A famous medieval fortress, built entirely of hewn stone. It was begun by Edward in 1283. The first Prince of Wales is said to have been born here.

A vassal could hand over part of his territory to a subvassal, who would then stand to him in the same relation as he himself stood to the king. Such subinfeudation was extremely common. The subvassals again did the same. Thus a kingdom was broken up into an indefinite number of large and small fiefs. Each prominent man, as a rule, was at the same time lord and vassal: lord toward his own vassals, and vassal toward his lord. To this it must be added that the rights and duties were in each case fixed by contract, although usage had induced a certain uniformity. The king or lord might give more of governmental rights to one vassal than to another.

A certain ceremonial attended the act of investiture. The vassal knelt before his lord and, placing his hands in or between his lord’s, pronounced the oath of fealty or homage. The lord then surrendered the fief to him — invested him with it — by handing to him something that was representative of it, as a clod of earth or a bunch of ears of corn, or, especially in the case of the higher fiefs, a glove or a spear with a banner. Then followed the lord’s promise of protection and the kiss of peace. The act of investiture was less solemn in the case of smaller fiefs.

468. How did a man become a vassal? So far we have had in view the cases in which a vassal received a fief not yet in his or in his father’s possession. Such a fief was a benefice. It must be kept in mind, however, that originally there was very much land which did not in its possession depend on any lord, but was the owner’s full property, — save for the rights of the king as sovereign head of the state. Such possessions, called allods, often were very extensive, and the owner naturally would divide them up among vassals. If an allod was small, the owner might find it more advantageous to be the vassal of some mighty lord than to be exposed to attacks of powerful enemies. He might then proceed to the act of commendation, that is, he surrendered his property to the lord and received it back from him as a fief, taking upon himself the usual obligations or such as were agreed upon. In the ages of insecurity commendation was constantly reducing the area of allodial land, so that the slogan, “no land without a lord, no lord without land,” pretty well expressed the actual condition.

RELATION BETWEEN LORD AND VASSAL

469. Position and Obligations of the Lord. — The vassal was far from considering his position degrading. Those only were vassals who were not obliged to work with their hands. The lowest vassal had his estate worked by serfs and villeins (see § 475). Both lord and vassal belonged to the nobility. In fact, they lived on terms of familiarity and mutual respect. Was the king himself, after all, more than a vassal of God? The lord was admired and almost worshiped by his people; and in return, however harsh himself, he permitted no one else to injure or insult one of his dependents. An honorable noble, indeed, lived always under a stern sense of obligation to all the people subject to him. A rough paternalism ruled in society.

The sacredness with which the lord considered his duty of assisting his vassals is graphically pictured in the Nibelungenlied, the greatest German epic of the Middle Ages. King Gunther undergoes the utmost hardships and dangers rather than deliver one of his vassals to the vengeance of a personal enemy.

It goes without saying that all lords did not come up to his ideal. Many no doubt seriously abused their power. By doing so, however, they brought upon themselves general contempt and hatred.

470. The vassal’s obligations, after the system had become more or less fixed, may be summed up chiefly under three heads:

(1) The vassal was to present himself, at the call of his lord, to serve in war, — perhaps alone, perhaps followed by an army of knights and men-at-arms, according to the size of his fief. He could be compelled to serve a fixed time each year, commonly only forty days, but for that time he was to maintain himself and his men.

The short term of service made the feudal array of little use for distant expeditions; and indeed vassals were sometimes not under obligation to follow their lord out of the realm. The jealousies among the vassals, and the absence of any power except that of a lord over his immediate followers, tended to diminish the cohesion which an army needs in order to be efficient.

(2) The vassal was hound to serve also in the lord’s “ court,” usually at three periods each year. The court had two distinct functions, (a) As a judicial body, it gave judgment in legal disputes between vassals; and (b) as a council, it advised the lord in all important matters.

A vassal, accused even by his lord, could be condemned only by this judgment of his peers (Latin pares), or equals. The lord was only the presiding officer, not the sole judge. The second office of the court was even more important: the lord could not count upon support in any serious undertaking unless he first secured the approval of his council. In feudal language, the council “advised and consented.” This expression, through English practice, has come down into our Constitution: our President is empowered to do certain things “with the advice and consent ” of the Senate.

(3) The vassal was to make four kinds of financial contributions, (a) Upon receiving a fief, either as a gift or as an inheritance, he paid the lord a sum of money. It was called a relief, and commonly amounted to a year’s revenue. (b) If the vassal wished to sell his fief, or to sublet part of it, he was obliged to pay for the lord’s consent, (c) Upon other occasions he made payments known as aids. The three most common purposes were to ransom the lord, if a prisoner, and to help meet the expense of knighting the lord’s eldest son and of the marriage of his eldest daughter. (d) Similar to such payments, but more oppressive, was the obligation to entertain the lord and all his following upon a visit. Frequently, however, it was set forth in the contract how often the lord might call, and how he was to be treated. (On other claims of the lord upon the fief see Modern World, § 121.)

471. Peculiarities. — To understand the system fully and to realize to what complications it was able to lead, the student should keep in mind several peculiarities:

(1) The vassal was hound to his lord, but not to his lord’s lord. Hence the maxim, “My vassal’s vassal is not my vassal.” Hence, too, there was no appeal from the lord’s verdict to the over- lord. The king only, as the supreme champion of right and justice, might interfere, but he was far away and it was rarely ppssible to lay the matter before him. Nor was a subvassal guilty of treason if his lord offended against the higher lord and summoned the subvassals to a war against the latter. The vassals were like so many little kings, each in his own small or large fief. The system tended to a complete decentralization of power. France at one time was divided among some 70,000 fiefholders.

(2) A man could hold fiefs from different lords. He then became the vassal of two or more lords. When taking his oath of fealty he would, in such a case, expressly reserve the rights of his first lord, and he could not be forced to war against him. He might take land from one who otherwise was his inferior on the social ladder, even from his own vassal. The obligations were always laid down in carefully worded contracts. It is evident what a complication of relations — we are strongly inclined to call it confusion — could thus be brought about.

(3) Not only individuals but corporations as well could enter into the relation of lord and vassal. This is particularly true of ecclesiastical institutions, as bishoprics and monasteries. From rulers and other pious persons they obtained property of both kinds, allodial and feudal. By the latter the bishop or abbot or abbess became a vassal, obliged to furnish a certain number of soldiers to the lord, who might or might not be the king himself. According to the laws of Church and State, however, clerics were not allowed to fight in person. Their possessions, allodial and feudal, they might hand over to vassals. It was the ecclesiastical institutions, too, that received proportionately many possessions by way of “ commendation.” The burdens they imposed were as a rule lighter than those exacted by lay lords. Besides, the lands thus surrendered became ecclesiastical possessions and enjoyed the special protection granted by stringent laws of the Church against violators of sacred property. — Later on when the cities rose to importance, they also might accept or grant fiefs.

HOW DID THE SYSTEM OF FEUDALISM ARISE?

469. Roman and Germanic Institutions. — It must not be imagined that feudalism sprang into existence in its full final shape as suddenly as a new system of education is introduced by some city or state. It took centuries to grow. Its beginnings go far back into the time before Charlemagne. The great landholders found it easier to divide their immense estates among tenants who paid their rent by services. This practice existed in the later Roman Empire (§ 385) and may have been taken over by the Germans. Besides, the kings of the invading nations always received a very considerable share of the estates taken from the old inhabitants. They roped off sections of them to their followers, who in return were obliged to supply a certain number of warriors. The system increased very rapidly during the period of unsafety under the later Carolingians, when the owners of large districts surrounded themselves with bands of loyal followers (§ 390) to repel attacks of rapacious neighbors or even foreign enemies. It was then that the practice of commendation (§ 468) assumed large proportions. The little army of the lord was ever ready or could be collected almost at a moment’s notice. At this time, too, the counts appointed by the kings often succeeded in making themselves feudal lords of their districts.

Originally every freeholder (owner of allodial property) was bound to military service in the king’s army, though these national troops were rarely summoned. With the decrease of the number of freeholders, in consequence of “ commendation,” or of violence on the part of some mighty lord, the contingents of the freeholders in the royal army also decreased, so that the king’s force more and more came to consist exclusively of the levies furnished by his vassals.

473. The rich landowners came into prominence because they could equip themselves with horses and armor. The infantry, once the main part of the national army, lost its importance when the Arabian or Hungarian raiders appeared on their fleet horses or the Danes in their light boats. The swift, mail-clad horseman now became the main reliance. As every warrior had to supply his own equipment, only the wealthier could afford serving on horseback. This circumstance partly caused, and at any rate tended to perpetuate, the difference between the poor peasant and the nobleman, whose sole occupation consisted in fighting or being ready for fighting (§ 476).

The nobleman’s castle at the same time afforded protection to his serfs and villeins. In its fortifications they found a refuge when an inroad threatened, and though their modest dwellings might be burned down, at least their lives were safe, and they could return to their fields after the storm had swept by.

Thus feudalism arose out of a great variety of causes. And though it always supposed the existence of a supreme head of the state, it owed much of its predominance to the fact that the kings were not always powerful enough to meet the ever-repeated attacks of foreign foes.

474. Nobility. — Those men only who were not obliged to work with their hands made up the feudal world in the strict sense of the term. They alone were able to equip themselves with everything necessary to serve on horseback. At first it was the possession of a fief or of property sufficient for this purpose, and other reasons, which sharply distinguished them from the rest of the people. They and their descendants formed the nobility or knighthood, for which the property qualification alone was no longer sufficient or necessary. Not all those of noble lineage actually possessed fiefs or allodial property. Many were simply attached to some great lord. But they alone might be invested with fiefs or enjoy certain other privileged positions at the courts of the mighty.

475. The Workers.—The fields were tilled by serfs and villeins (the latter word from the Latin villa, rural possession). They stood, however, in a relation to their lord somewhat similar to that of the noble vassal. They received moderate farms, the products of which were their own. Instead of rendering military service they were obliged to serve a specified number of days in the lord’s fields, and had to deliver to him a certain share of their own crops. There existed of course no social equality between them and their masters, from whom they and their children remained socially separated by a hard and fast line. Still a beautiful, not to say cordial, relation often existed between the lord and his peasantry. The serfs, as in the later Roman Empire (§ 385), were bound to the soil and were bought and sold with it. Their condition was often miserable, because they depended greatly on the whims of their master. (See, however, § 483.) The villeins might leave the lord’s service if they pleased, just as a tenant is at liberty to give up the farm he has rented. But it was risky for him to remain without any other master. The lordless and landless man could count on little protection.

Serfdom and villeinage ran into each other in the most confusing manner, so that they are often referred to under either name. This dependent class had partly arisen out of the old slavery, which existed among the Teutons also. Owing chiefly to Christian influence slavery had greatly diminished. Nor was there any slave trade deserving the name. Villeinage and serfdom often originated by something similar to “ commendation ” (§ 468). In the troublous times the free peasant might prefer the safety of the dependent worker to the insecurity of his own freedom. He preferably sought the protection of the ecclesiastical institutions, such as monasteries or bishoprics, by surrendering himself to their service. Written contracts specified the burdens he was going to take upon himself.

In some regions, the Swiss mountains for instance, a large number if not all of the farmers remained free. In the course of time, too, the lot of the dependent worker improved greatly, so that preachers inveighed no less against the extravagance of the peasants than that of the other classes.

MILITARY FEATURE OF FEUDALISM

476. Castles. — The nobleman’s residence and the heart and center of the fief was the castle (from the Latin castellum, fort). In the beginning the castles were merely wooden blockhouses surrounded by palisades and ditches. But they were soon followed by massive stone structures. The main part of the medieval castle was the keep, a very strong tower, in which originally the lord’s family would reside. In case of assault it served as the last refuge. Its walls were often enormously thick, so that a man crawling out of a window would have to creep three times his length. The stairway was sometimes concealed within these walls. Connected with the keep were other buildings for the servants and the provisions harvested from the lord’s fields. Very frequently the castle crowned the top of some steep hill, where it was often surrounded on one or more sides by precipices. If erected in the plain, the castle was protected by a moat, a ditch filled with water, over which usually a drawbridge gave access to the strongly defended gate. (Note the portcullis, a heavy iron grating which could be dropped from above, in the picture on opposite page.) The gate was often flanked by towers from whose slitlike windows bowmen could harass the assailants with their arrows. As the art of building progressed the lord’s family no longer dwelt in the narrow and gloomy keep, but in a more elegantly constructed section or in an extra “hall.” Our two illustrations show types of such sumptuously built castles.

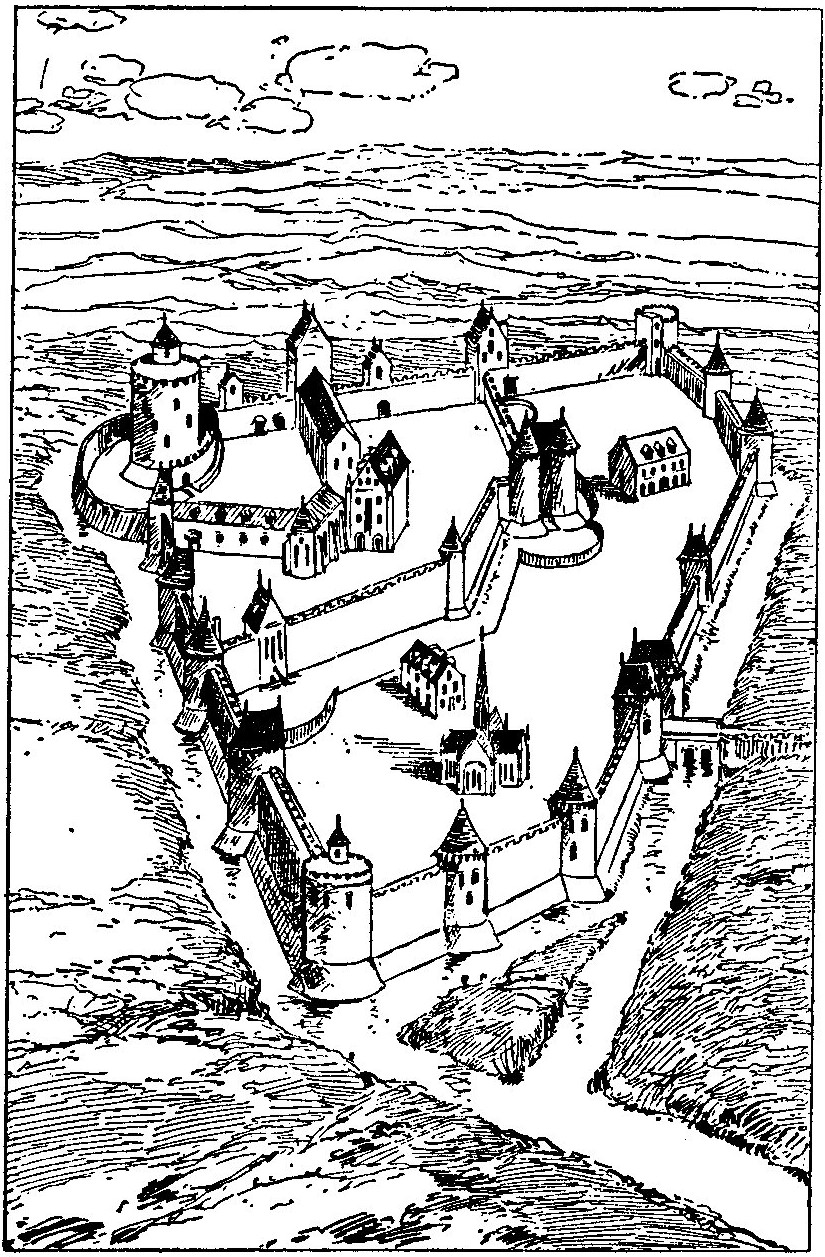

This is the larger sort, with moat and drawbridge. A restoration, from Gautier’s La cevalerie.

Until the days of gunpowder, feudal castles were virtually impregnable to ordinary attack. They could be captured only by surprise, by treachery, or by famine. Secure of such retreat, a petty lord could sometimes defy even his own sovereign with impunity. Too often the castles became themselves the seats of robber barons who oppressed the country around them. To-day their gray ruins all over Europe give a peculiar picturesqueness to the landscape, mocking, even in decay, the slighter structures of modern times.

477. Men-at-Arms. — The castles afforded a refuge for man and a place of safety for treasure. But during the invasions, the problem in the field had been to bring to bay the swiftly moving assailants, — the light horsemen of the Hungarians, or the Danes with their swift boats for refuge. The Frankish infantry had proved too slow. Feudalism met this need also. Each castle was always ready to pour forth its band of trained and faithful men-at-arms (horsemen in mail, knights), under the command of the lord, either to gather quickly with other bands into an army under a higher lord, or by themselves to cut off stragglers and hold the fords and passes. The raider’s day was over; but meantime the old Teutonic foot militia, in which every freeman had held a place, had given way to an iron-clad cavalry, — the resistless weapon of the new feudal aristocracy.

It was restored in the fourteenth century.

478. Armor. — In the early feudal period, down to 1100, the defensive armor was an iron cap and a leather garment for the body, covered with iron scales. Then came in coats of “chain mail,” reaching from neck to feet, with a hood of like material for the head. Still later appeared the heavy “plate armor,” and the helmet with visor, which we usually associate with feudal warfare. A suit of this armor weighed fifty pounds or more; and in battle the warrior bore also a weighty shield, besides his long sword and his lance. Necessarily the war horse that carried a heavy man so equipped was a powerful animal; and he too had parts of his body protected by iron plates.

The supremacy of the noble over common men during the Middle

Ages (before the invention of gunpowder) lay mainly in this equipment. He could ride down a mob of unarmed footmen at will. The peasants and serfs who sometimes followed the feudal army to the field, to slay the wounded and plunder the dead, wore no armor and wielded only pikes or clubs and pitchforks. Naturally they came to be called infantry; that is, boys (from the Latin infantes, children).

Crosses mark monasteries; circles, cities.

479. Private Wars and the “Truce of God.” — The nobility was an ever-ready militia, consisting of professional fighters, who thought of war as a most honorable occupation. It is not surprising that they would often refuse to submit to whatever courts there were, and would prefer to settle their own disputes by an appeal to the sword instead of to the law. The lords of the castles claimed the right of private warfare. The result was in many parts of Europe a new general state of insecurity which hindered the growth of industry and severely damaged agriculture. There was a crying need of some antidote, but who would be able to give it?

In the beginning of the eleventh century the bishops of France introduced the Truce of God. There was to be no private warfare during the holy seasons of Advent and Lent. During the rest of the year it remained forbidden from Wednesday night of each week until the morning of the following Monday. Thus the Truce of God established about 240 days of peace every year. Transgressors were threatened with the severest spiritual penalties. This law found its way into other states. It was probably never completely observed in any region, but even its partial observance greatly tended to diminish the devastations and other evils of private wars. For France it was of the greatest importance. It was, says an historian, “the first step in the making of France,” because it curbed “by religious discipline the powerful but turbulent elements of that gifted race.”